Celeste is a side-scrolling precision platformer that explores themes of coping with mental illness through the metaphor of climbing a mountain. The player character is Madeline, a young woman suffering from anxiety attacks and issues of self-worth who resolves to conquer her demons by climbing the titular mountain. The climb proves even more dangerous than Madeline anticipates; the mountain is haunted, and its challenger must conquer supernatural forces in addition to the physical difficulty of scaling a stony peak. During her climb, Madeline overcomes the ghost of a clingy hotel concierge, navigates a labyrinth of magic mirrors home to shadowy monsters, and gets stalked by her own dark reflection, a manifestation of Madeline’s fears and doubts that desires to prevent her from reaching Celeste’s summit. Only by facing these challenges and others across seven chapters of tight precision platforming can Madeline reach her goal and prove her own sense of self-worth.

Celeste is a wonderful example of a videogame capitalizing on simple controls to create a deep and varied experience. Madeline has just a few skills with which she summits the mountain. Her most important skill is an incredible jump which is unimpeded by the heavy pack strapped to her back and an apparent lack of physical training. She has the supernatural prowess of typical platforming protagonists, able to perform a standing jump over twice her height and then defy physics as she controls her momentum through the air. Her supernatural powers are necessary. The mountain is filled with treacherous terrain, and often the only way forward is by perching on a platform barely wide enough to support her feet. Precision platformers demand exacting controls—precision is right there in the name—and Celeste lives up to that demand.

Madeline’s other platforming skills are also fantastic, though with more obvious limitations. Almost as important as her jump is an air dash that propels her in any direction from midair. This extra airtime lets her impossibly bend her jumps around corners and over walls. Her other platforming skill lets her interact with the mountain’s many vertical surfaces. When Madeline impacts a wall, her body will attach to it. From there, she may slide downward or jump again in a classic wall jump. If I hold down the gamepad’s shoulder button, Madeline will grip the wall, allowing her to climb up or hold still, waiting for conditions to change before moving again. Madeline’s stamina is curiously only limited for these two exact actions; if she tries to grip or climb for too long, her hands will fail and she will fall. Her air dash and grip strength regenerate instantly once her feet touch solid ground once more, even if only for a moment.

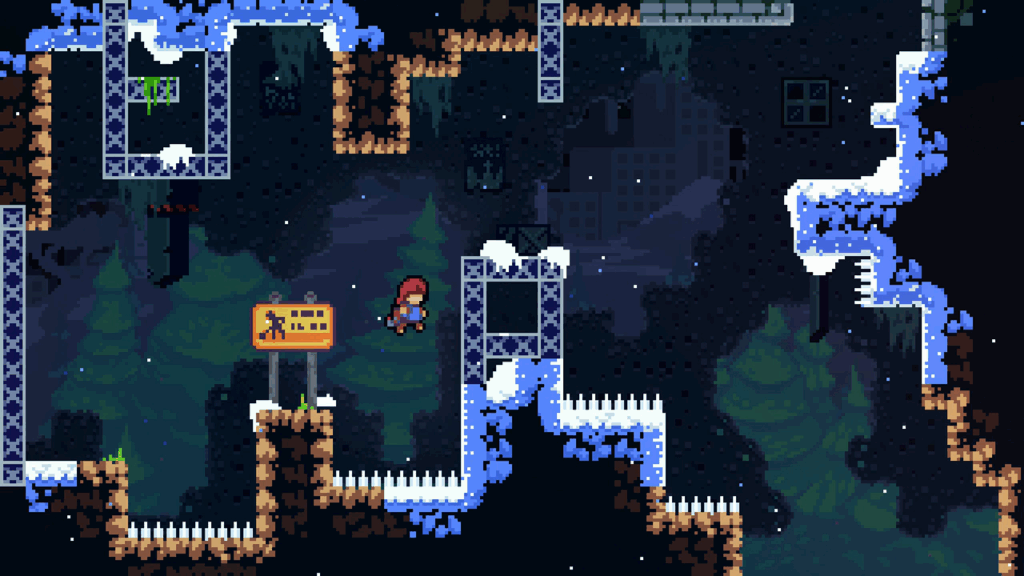

Despite the simplicity of Madeline’s moveset, the limits placed on her powers are still a lot of information to convey on screen. Celeste cleverly keeps its interface clean by communicating these details through Madeline’s avatar. Her hair changes color to signify her air dash’s status, from her natural red when she may use it to a cold blue when it is unavailable. When Madeline’s grip strength fails, her entire body flashes red. By keeping these indicators on Madeline and not on an icon at the screen’s periphery, my attention remains focused on her location in the hazardous environments.

The spaces where I help Madeline apply her platforming skills are divided across hundreds of distinct screens. There is little uniformity in their design. They may be tall, short, wide, or narrow, with the camera panning to follow Madeline as she moves across them. The perimeters between each screen act as a checkpoint to which Madeline will generally return when she dies. Though her platforming skills are formidable, Madeline is fragile, dying to a single touch from any of the mountain’s hazards.

I expect the most frequent danger on the mountain will be a fatal fall. Though deadly pits are common, falls are almost always the least of Madeline’s worries. She isn’t even injured by impacts, always landing on her feet with a gentle plop as though she dropped from no higher than a stairstep.

The mountain’s real dangers are typical of what I expect to see in other platformers. Falling blocks and moving platforms are numerous. The most frequent dangers are spikes that saturate the walls, floors, and ceilings of almost every space. While I may sometimes assume spikes are actually icicles naturally occurring in the mountain’s frigid climate, they have an industrial uniformity that resembles the death traps meant to snare Mario or Meat Boy more than the natural features of a crumbling mountainside. While I might like to see a more organic approach to the visuals, the immediate readability of the innumerable spikes as deadly obstacles adds to Celeste’s authenticity as a precision platformer.

To keep things fresher than a gauntlet of falling blocks, bottomless pits, and deadly spikes, new platforming devices that change how Madeline moves through a platforming challenge are introduced at each step of her summit. Each device is explored from its simplest application to its most complex and esoteric over the course of a single level. Just when it seems like the idea is about to break under the creative tension, the chapter ends, the device is discarded, and Madeline is thrust into a new environment with a new mechanic.

In addition to refreshing the platforming every chapter, the new devices help to emphasize each chapter’s particular theme. Set in the ruins of an abandoned city near the mountain’s foot, Chapter 1 is filled with mechanized blocks that burst to life when Madeline touches them, thrusting forward with the power of a piston. Sometimes they create the momentum to thrust Madeline across long gaps, sometimes they threaten to crush her against a wall—and sometimes they do both at the same time. Chapter 2 sees Madeline overwhelmed by her ordeal in the Forsaken City and falling asleep in front of a monument to everyone who has died during the ascent. It is a much more dream-like level where blocks filled with starlight will only allow her to cross their surfaces in perfectly straight lines.

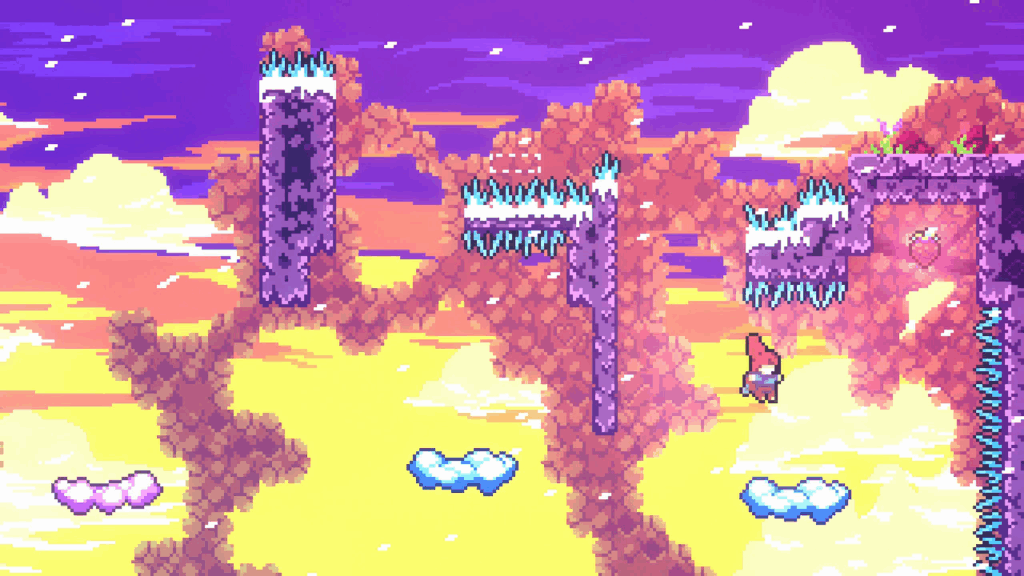

Mechanics explored in later chapters are not always more complex. They include surfaces that kill Madeline if she touches the same spot twice, clouds that behave like trampolines, and the side-scrolling platformer classic of powerful wind gusts that alter the player character’s jumps. Celeste changes ideas often enough that I don’t have time to get bored or frustrated with what a particular chapter is doing, constantly resetting the status quo without discarding the fundamentals that drive the platforming. It’s not just a masterclass in videogame design; it’s seven masterclasses (and more) in one.

Celeste’s collective challenges are meant to add up to a purposefully difficult videogame. It is expected for Madeline to die dozens or hundreds of times in a single chapter. Postcards preface each level, and one gives this advice: “Be proud of your Death Count! The more you die, the more you’re learning. Keep going!” Deaths are building blocks representing my developing skill, not demerits indicating my failures. Among Celeste’s online communities, each player’s death count is shared as a badge of honor.

It’s easy to build up an incredible death count. Though the player character is fragile and levels are intentionally designed to be grueling, Madeline instantly reappears at the last checkpoint whenever she succumbs to the mountain’s hazards. Non-gameplay obstacles in other videogames, like game over screens and loading times, create considerable friction for a player; sometimes waiting for the videogame to allow me to retry is more frustrating than repeatedly failing a challenge. Celeste does not give me a moment to feel friction from extraneous elements. As soon as Madeline dies, she is ready to go again immediately. This transforms a difficult platforming sequence into a meditative, almost compulsive activity.

Though Celeste may be intentionally difficult, I still have a great deal of control over just how hard my experience will be. The first degree of control I have is which challenges I choose to pursue. My mistakes while guiding Madeline to the mountain’s peak get her killed exactly 1000 times. That death count would be much lower if I did not push her to reach for every Strawberry she passes along the way.

Strawberries are Celeste’s collectables and they are no ordinary fruit. They are the size of Madeline’s head and float in midair, almost always precariously placed near a deadly obstacle or beyond a taxing set of jumps. Reaching them requires Madeline to complete an otherwise optional section of the screen or manipulate its devices in an unorthodox way. The most difficult Strawberries are placed in hidden screens placed off the obvious forward path, allowing the level design to maximize the space to create astonishing obstacle courses. Completing them are true feats of skills.

The best thing about Strawberries is they are totally optional. Another postcard advises that “Strawberries will impress your friends, but that’s about it.” This is almost a lie. The number of Strawberries Madeline collects does change the still image that ends the story. It otherwise has no effect. Madeline will navigate the same levels, interact with the same characters, and reach the same emotional catharsis no matter how many Strawberries I force her to collect. She could have a much easier time climbing the mountain and get there much faster if I ignored them. Only my admiration for Celeste’s platforming design and my pride push me to guide her towards as many as possible.

Everything I have written about Celeste up until now has described its mechanics in their default state. The Assists menu allows me to toggle several options that modify Madeline’s fundamental performance. If the gauntlet of spikes and other hazards appearing in most areas is too much, I may activate Invincibility, transforming the mountain’s deadliest environments into a pleasant stroll through a mountain passage. I may alter Madeline’s air dashes, allowing her to use as many as she wants without having to touch the ground. Disabling Stamina is perhaps the most impactful Assist. The challenge in many screens is reaching their exits before Madeline’s stamina drains. Having infinite stamina creates situations where she simply has to climb to her goal.

Celeste is refreshingly non-judgmental about the use of its Assists. Turning one on does not restrict me from accessing any of Celeste’s content or earning any of its achievements. It is intended to make every inch of the mountain’s secrets accessible to every player, not just the ones who can overcome its most difficult challenges as they are originally designed.

I can already hear insignificant voices arguing that an accomplishment “doesn’t count” if it was not obtained under the hardest conditions. What they do not understand is that how somebody else accomplishes their goals has no impact on how I accomplish mine or you accomplish yours. Celeste is a videogame. It should be fulfilling, and fulfilling for everyone, however much that is possible. I don’t know that these Assists will make the haunted mountain accessible to every potential player. I appreciate that Celeste tries something to accommodate all kinds of players other than an indifferent shrug.

I’m glad that Celeste makes the effort to be accessible because it has messages and themes that are important for as many people as possible to experience. It’s apparent from the outset that Madeline suffers from a high degree of anxiety; the first thing I see upon beginning a new game is not the mountain’s first screen, it is Madeline reminding herself to breathe. As she ascends the mountain, the many near-death situations she endures cause her to have multiple panic attacks. Without diagnosing her, it is apparent that Madeline is not a well person.

Narrative rules being what they are, the mountain turns out to be exactly what Madeline needs. Her climb is an eye-rollingly apt metaphor for overcoming her mental illness, the troubles she experiences on the way coinciding with her rising and falling mental state, and the inevitable moment when she reaches the summit aligning perfectly with her finally overcoming her anxiety attacks—though perhaps not forever.

Since the mountain is haunted, Madeline’s doubts and anxieties are able to manifest themselves in frighteningly physical ways. Early in her climb, she discovers a mirror deep in a ruined fortress. Out from this mirror climbs a character only ever called Part Of You, a dark reflection of Madeline who taunts her with her worst fears and doubts and often physically interferes to prevent her progress upward and forward. It is how Madeline deals with Part Of You that is central to Celeste’s messages about mental illness. No matter how many times Madeline defeats Part Of You, she always comes back. Madeline must find another solution to dealing with her other self. Only when she finds it does the mountain become climbable.

After I have helped Madeline reach the mountain’s summit, there is still much more to discover. Hidden in each level are Crystal Hearts, special collectables with obscure methods for revealing and reaching them. Collecting enough of them opens a new door in the heart of the mountain, leading to the secret eighth and ninth levels. Level 8 isn’t too much more difficult than the preceding seven levels. Level 9, in both length and difficulty, is one of the hardest platforming challenges I have ever encountered. I am grateful that these two levels exist outside the core narrative and the story is not incomplete if I or any other player is unable to get past them.

While searching for the Crystal Hearts, I am likely to discover audio cassette tapes also hidden in each level. Collecting one of these tapes unlocks that level’s B-Side. B-Sides are remixes of each level’s core mechanics. They are shorter than the A-Side but make up for it with extra difficulty. Finishing a B-Side unlocks a C-Side, which is yet more difficult. B-Sides and C-Sides exist completely outside the narrative, existing to push my platforming skills to their highest instead of advancing the story. Beating Celeste’s core seven chapters takes me about six hours and 1000 deaths. Collecting every Strawberry and Crystal Heart, beating the two bonus levels, and completing every B-Side and C-Side adds up to many dozen hours more and deaths into the tens of thousands. It’s a serious proposition that should not be undertaken lightly by even the most experienced player.

I try not to be hyperbolic on Play Critically. I try not to say a game is the “worst ever” or the “best ever,” and when I do praise is hedged by minimizing it to a calendar year or to that particular videogame’s place in the zeitgeist. Celeste tests my policy. Or maybe it doesn’t—is it hyperbole when it’s true? Celeste may be one of the greatest platformers ever made. Its mechanics are platforming at its most sublime, artfully simple, perfectly precise, and requiring hours of practice to master. It strikes an incredible balance between difficulty and satisfaction, pushing my skills to their limits and rewarding me with awesome catharsis when I finally overcome a particularly tricky section. What really tips it over the edge is it’s the rare platformer that’s actually about something. Celeste is one of the most incredible works of art in recent memory—in any medium.