Core Keeper is a survival and crafting-focused sandbox set in a subterranean wilderness. I play as a miscellaneous member of an expedition who comes across a stone monolith in a deep forest. The player character is drawn to touch the blue gem at the monolith’s center, and when their palm makes contact, they are transported to a cavern next to an identical monolith. Exploring this new space reveals they are now trapped in a vast underground world filled with alien ecologies, the crumbling ruins of extinct civilizations, and signs that my player character is far from the first unwitting victim to be transported to this space. Guided by messages whispered to them by the monolith, the Core, my player character must master this new environment, transforming the inhospitable cavern into a warm and bountiful home where they manufacture the tools that let them survive and thrive. Only by completing the Core’s requests to hunt down and kill nine colossal monsters hidden around the procedurally generated world can the player character hope to escape back to their home.

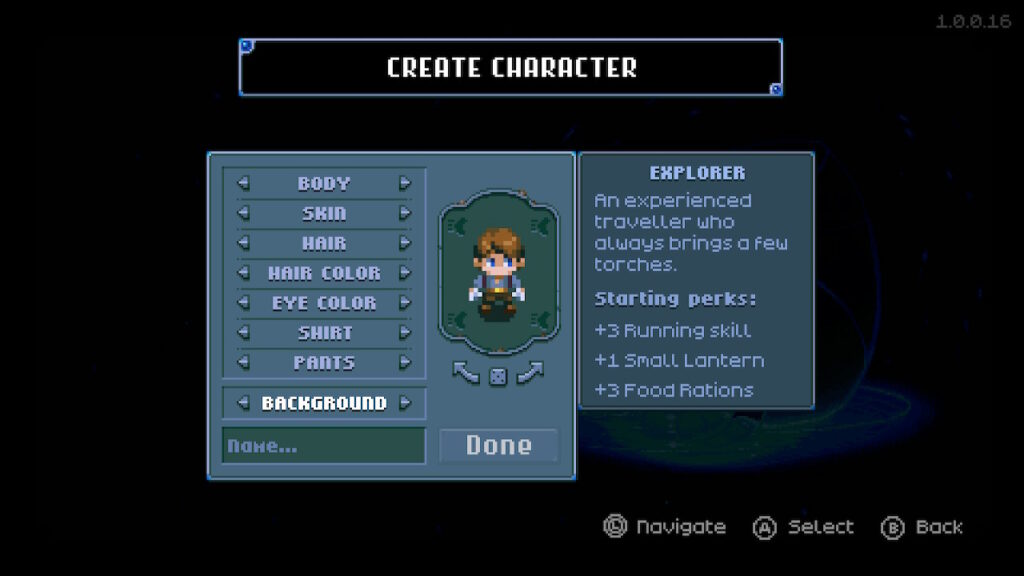

In the dozens of hours it takes me to help my tragic player character escape from the subterranean world, I sense Core Keeper’s design transitioning through distinct phases. In the first phase, the player character has been transported carrying only whatever was related to their former occupation: a lantern, some rations, a sword, a cooking pot, or even nothing at all. Their fragile health meter may be depleted by the subterranean world’s many predatory monsters and their hunger meter drains constantly, further weakening them as it empties. Seeing to these immediate needs is the first hurdle the player character overcomes.

Outfitting, feeding, and sheltering the player character begins in the grand tradition of survival and crafting sandboxes since the advent of Minecraft: By punching the nearest trees and rocks with their bare fists, or as befittingly translated to Core Keeper’s underground world, the nearest roots and cave walls. Using the wood and stone scavenged from around the Core, the player character crafts rudimentary tools. A sword to defend themselves. A pickaxe to break cave walls. A shovel to dig. These crude tools expand where they are able to travel and the resources they may gather, allowing them to slowly ascend a tech tree until they wield a sword made of mythical metal and a pickaxe that can shatter any obstacle. This is a familiar progression in survival and crafting design and Core Keeper does little to distinguish itself in a sea of fellow imitators.

What does make Core Keeper feel distinct is its perspective. It is played from a top-down view a considerable distance away from the player character, as though I am seeing through an eye peering down into the subterranean world from a perch on the ceiling hundreds of feet above. The sandbox is built on an invisible grid, giving the textures decorating the floors and the walls creating defined spaces an angular appearance. The individual squares of this grid are tiny, displaying hundreds on screen at once.

The collective number of squares portrayed at once grants incredible scale to the environments, particularly the wide spaces the player character explores in the latter half of the scenario. The tiny individual squares can also make the world difficult to precisely interact with. When the player character begins making their own structures in the landscape, it’s a massive undertaking, mitigated only a little by building blocks stacking up into the thousands in a single inventory space. The player character assembles dozens of unique crafting tables to create these objects and activating the precise one I want in a crowded space can be difficult. Playing with a mouse-guided cursor instead of a gamepad is to Core Keeper’s great benefit.

Apart from scavenged resources, the elements that have the greatest impact on how the player character interacts with the subterranean world are their skills. Everything they do develops their proficiency at a particular skill, so the best way to get better at an aspect of survival is to throw the player character into it. Breaking walls improves their Mining skill. Digging out a small farm and growing the subterranean world’s unique plants—that somehow grow without photosynthesis—increases their Gardening skill. Cooking food in a pot increases their Cooking skill. Even Running is a skill that naturally develops to a high level the more time the player character spends moving around the subterranean world.

Every five levels the player character gains in a skill, they earn a perk point, and every skill has a small perk tree into which they may be invested. Perks radically improve the player character’s performance in a specific way and are the real benefit in improving skills. Mining perks can increase the power of their strikes against cave walls or cause their pickaxe to restore durability instead of draining when swung. Gardening perks can increase the quantity of food gained from a single plant and cause seeds to appear when harvesting a crop, creating a self-sustaining loop of plantlife. Some crafting perks increase the number of items produced from the same set of resources, which can be a major boon when the player character begins the important task of transforming the environment. Points invested into perk trees may be refunded using an easy-to-acquire currency, encouraging me to experiment or reforge my character as they encounter new hardships.

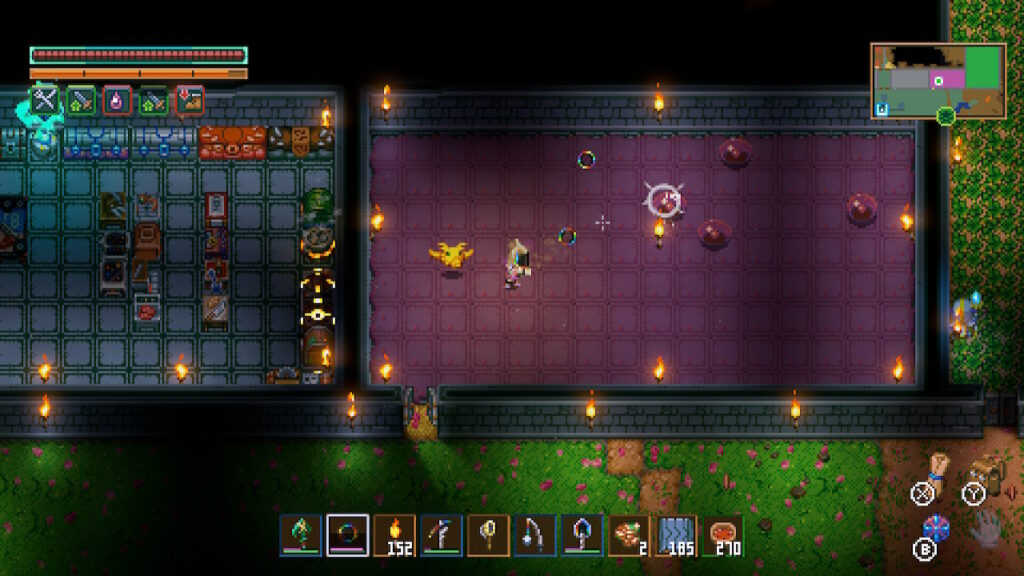

The other major aspect of Core Keeper ruled by RPG skills is its combat. The same principles apply: Using a specific type of weapon improves the player character’s ability with that type, so they should dress for the job they want. Each variety has a radically different function, almost as though I begin playing a different videogame when the player character changes their equipped weapon. Melee weapons create a hack-and-slash feel, though outfitting the player character with a shield to absorb or parry enemy attacks is wise. When they use a ranged weapon like a chakram or bow and arrow, the controls transform into a twin-stick shooter. Magic weapons fire energy missiles similar to ranged weapon projectiles and confer many useful abilities, like a barrier that absorbs damage in place of the player character’s hit points, but are limited by a fast-regenerating mana meter. Summon weapons are the most unusual. Instead of dealing direct damage, they conjure a minion who will fight on the player character’s behalf for a short time for a hefty mana cost.

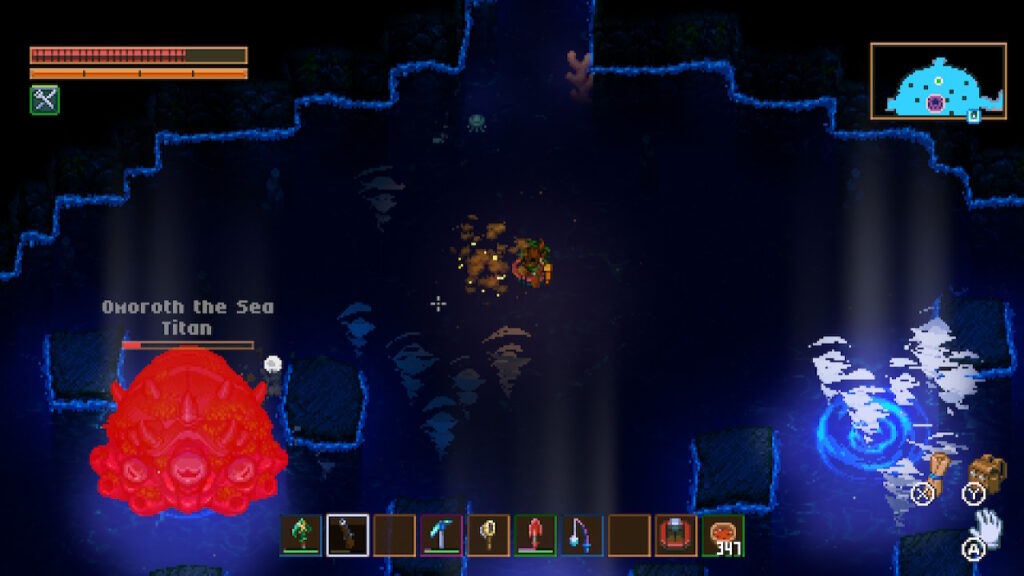

As the player character first sets out into the subterranean world, my plan is to have them focus on reliable damage with a melee weapon. For a time, this is effective. In the latter twenty-five hours of my playtime, melee weapons feel more and more useless. Spaces become wider than the cramped early areas near the Core. The environments become treacherous, filled with impassable chasms that make it difficult to close the distance to attacking monsters. It feels especially foolhardy against the Titans, the bosses the Core charges the player character with slaying. Their size, speed, and power demands mobility to avoid their deadly attacks. A sword’s need to constantly be in close range becomes a liability. As I dig into the center of Core Keeper’s mass, I regret the many hours I spend training my player character with a sword instead of a bow or wand. The bow feels necessary. The sword feels foolhardy.

This first phase of Core Keeper introduces me to all of these mechanics. While the player character amasses a collection of tools and weapons, scratches out a rudimentary base around the Core, and begins developing their RPG skills, they are guided to three bosses. None are too far from where the Core sits at the map’s center. The first two are relatively straightforward. They are brutes, but not unmanageably larger than the player character and susceptible to basic hit-and-run tactics.

The third boss is the exception. Ghorm the Devourer is a massive worm dozens of times larger than the player character and its size is matched by its indifference to their presence. It burrows through the subterranean world in a massive circle, leaving in its wake a sticky ooze that makes it difficult to chase. Hitting it hard enough to stop its endless circuit is the first challenge. Moving fast enough to avoid its attacks and retaliate is the second and more significant one.

Ghorm is emblematic of the bosses the player character must defeat in the subsequent two-thirds of my hours playing Core Keeper: Huge, fast, a test of the player character’s place on the tech tree, and a challenge of my skill at maneuvering them through a barrage of projectile and area effect attacks.

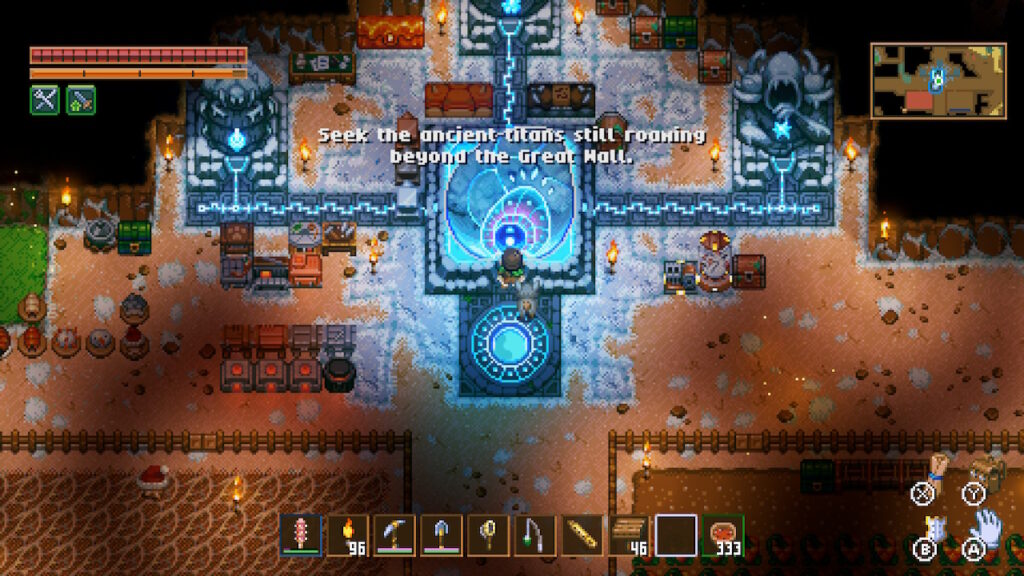

Not far past where Ghorm the Devourer makes his circuit is the Great Wall. This barrier marks the perimeter of Core Keeper’s earliest hours, the equivalent of stepping from an ocean’s shallows to its depths. The Great Wall will not lower until the subterranean world’s first three bosses are found and defeated.

The space inside the Great Wall is cramped and dense. The player character must burrow their way through thick rockbeds to reach small caverns containing interesting and odd features. Decorative gardens with small ponds are common, as though the lobby of a high-end office building has been transported to the subterranean world. Fields filled with golden grass contain cows, who can be tamed and enclosed in a pasture for regular collections of milk. Inside one cavern, the player character even discovers a deteriorated go-kart track connected to a small garage.

Beyond the Great Wall is where Core Keeper enters its second phase. The world here is a marked contrast to the confines near the Core. Spaces become vast and diverse. In one direction is a broad sea dotted with faux-tropical islands and the massive ruins of magical cities built directly on the water’s surface. In another direction is a desert where stone labyrinths rise from sands patrolled by aggressive exploding scarabs. A third area is a dense jungle. It feels most like the space inside the Great Wall, with thick walls of “forest” that must be cut through with a pickaxe. Mining through these blocks is probably meant to evoke jungle adventurers cutting through thick vines with machetes but the effect doesn’t work. It looks and feels like more digging through cave walls.

There are smaller discoveries to be made within and between these large regions. Small mausoleums dotted around the world will only open if the player character crafts a musical instrument and uses it to play the notes inscribed on their doors, revealing the treasures hidden inside. One sizable portion of the world has become infested by parasites. The cave walls here writhe and pulsate like they are the flesh of an agitated creature and armies of worms swarm around the trespassing player character, snapping at their legs with tiny mouths. At the outermost reaches of the map, the cave walls turn to crystals that only the most powerful tools may cut through. The world here is at its most alien. Massive snails with crystalline shells trundle through, mowing over any obstacle in their way, while the player character is hunted by creatures I would assume are robots if there was any sign of their creators.

Somewhere in these gigantic spaces are the remaining bosses the Core tasks the player character with defeating. Discovering them through pure exploration can take dozens of hours and I could believe that someone would derive a great deal of joy from thoroughly mapping Core Keeper’s procedurally generated world. For goal-driven players like myself, there are means to highlight the locations of these monsters. Expedience is purchased with some of the scarcest resources found in each biome.

Early on, the player character is able to get by using the resources they gather directly from the environment using their tools. Through commonplace exploration, they fill their pockets with enough ore, rock, wood, plants, seeds, bugs, and other miscellaneous objects to craft almost anything they need. The more time they spend in the subterranean world, the more they encounter certain resources that are always in scarce supply. This especially becomes a problem with the later Titans, for whom it is not enough to locate, but must also be summoned with an item crafted using many rare resources. A need grows for a continuous stream of certain materials without having to actively seek them out in the different biomes.

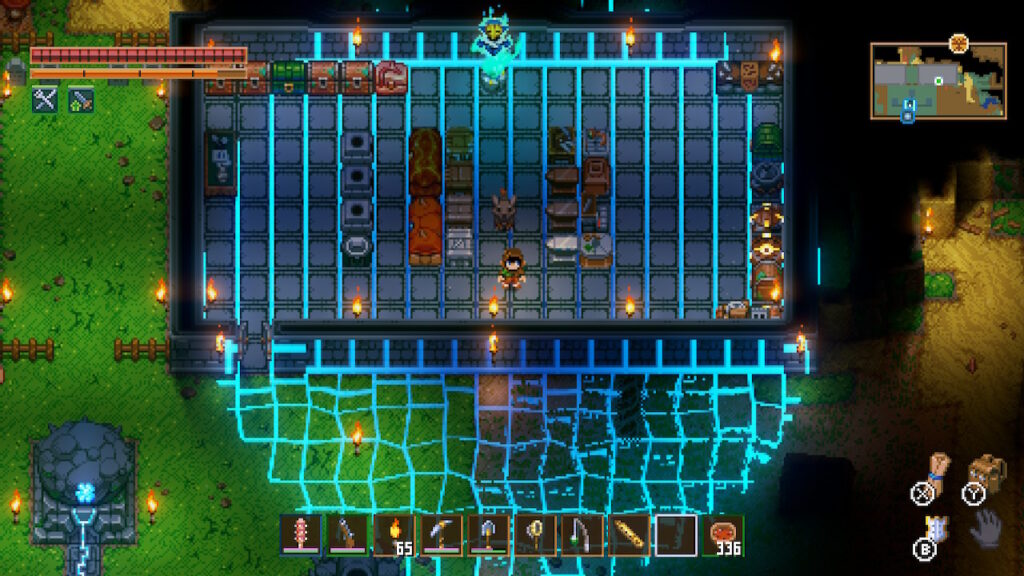

Core Keeper provides a number of ways to satisfy this need for automation. Sprinklers replace the tedious task of manually watering crops, allowing the player character to quickly plant seeds then move on to more important tasks. Similarly, the player character may set up drills to pick endlessly away at large ore deposits sequestered around the subterranean world. They may return periodically to claim the ore chunks mined by the drill, or set up a conveyor belt next to the drill to carry its yields to a more convenient point. Around my fortieth hour of playtime, conveyor belts stretch all across the subterranean world, carrying dozens of pieces of rare ore to the Core every few minutes. It takes a lot of setup but when it starts working, the results are immensely satisfying.

Not everything valuable in the subterranean world grows from a stem or is mined from a deposit. Some necessary items drop only from monsters, and usually uncommon ones at that. With a little extra effort, the player character can control where these resources are obtained as well.

Monsters do not spawn randomly. They are produced from special materials that lie on the floor, and these materials may be dug up and replaced anywhere in the world. This allows the player character to set up farms near the Core that produce monsters with especially valuable drops. Slime samples are a necessary component of healing potions. Scraping up slime patches from the floor and planting them in a room near the Core causes slime monsters to appear, creating a reliable source of samples the player character may claim every time they return from exploring. By the end of their time hunting the nine Titans, they have set up multiple rooms of this kind near the Core specifically to gather the rare items needed for cooking and crafting.

Core Keeper’s last major activity before transitioning into the endgame is using its automation tools to transform the subterranean world from a hostile, alien world into a productive factory that serves the player character’s convenience. There’s no requirement to do this. The player character could hunt and defeat all nine Titans through pure exploration. But it would take much longer, ignoring many of Core Keeper’s most advanced systems, and I believe would be much less enjoyable.

The final phase begins as the player character prepares to fight the final three Titans. This is where Core Keeper feels like it runs out of steam. The final Titans appear in the same general areas as the middle three. It’s even possible to summon and fight them in the exact same arenas. Instead of uniquely designed encounters against distinct monsters, the final Titans are all variations on the same basic design, only each one sprouts additional heads and uses a different elemental attack. As a final and especially annoying wrinkle, summoning the second Titan requires materials dropped only by the first Titan, and summoning the third Titan requires materials dropped only by the second. Dying too many times to one of the Titans requires the player character to re-fight their predecessor before they may try again, on top of gathering the other needed resources.

This entire phase feels lazily designed and padded, ending the player character’s time in the subterranean world on a sour note. It’s also a surprisingly brief one. It takes me more than 45 hours to explore every corner of the map, defeat the first six Titans, and create a massive system of automated resource generators. It takes me less than five to complete the last batch of bosses. It’s not only not much fun, it makes the massive world feel small and empty. It’s a disarming way to end my time with a videogame I otherwise enjoy quite a lot.

My deflating final few hours with Core Keeper’s main campaign are especially disappointing because this is clearly a videogame that wants to be replayed. It has a surprising amount of modularity. Characters are stored separately from worlds, so if I wish, I may take my player character from my world and join another player’s world or insert them into a brand new one, retaining all their developed skills and whatever they can carry. I can also take a fresh character and insert them into an advanced world, benefiting from prebuilt infrastructure but suffering from undeveloped skills. This flexibility makes Core Keeper ideal for multiplayer and players who really like to experiment with character builds.

Core Keeper is a long and involved survival and crafting sandbox experience, and how much enjoyment a player gets out of it is going to depend on how much effort they put into it. There are a lot of systems to explore and only a few of them may be selectively ignored without significantly impacting the experience. It’s at its best in its early and middle portions, when there are still new things to discover, new resources to exploit, and new equipment to craft for the player character. Its endgame is where it struggles. It feels like an ending to the scenario was included simply to have one. I wonder if I might still be enjoying Core Keeper if the map extended on into infinity. If the worst I can say of this sandbox is the only time I disliked it was in the last few hours of a fifty-plus hour adventure, I suppose that’s not such a terrible thing at all.