PowerWash Simulator places me in the role of the sole owner and operator of a pressure washing business. Outfitted with an upgradeable pressure washer, a wand connected to a hose that blasts water with incredible force, I guide the player character through dozens of job sites, cleaning up layers of dirt, grime, oil, and mold from vehicles, buildings, and entire stretches of property for an array of wacky customers. Jobs vary in size. Some may be completed in minutes. The largest can take more than five hours to finish in their entirety. As boring and absurd as this premise may seem, I find it to be a fulfilling experience that clarifies and reinforces why I love videogames—and not for some trite reason like being “fun.”

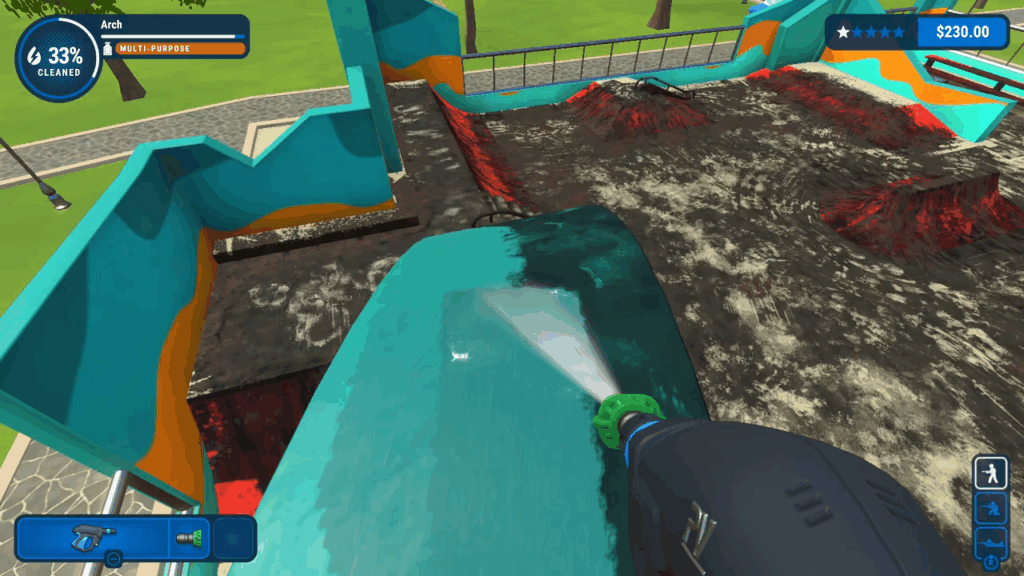

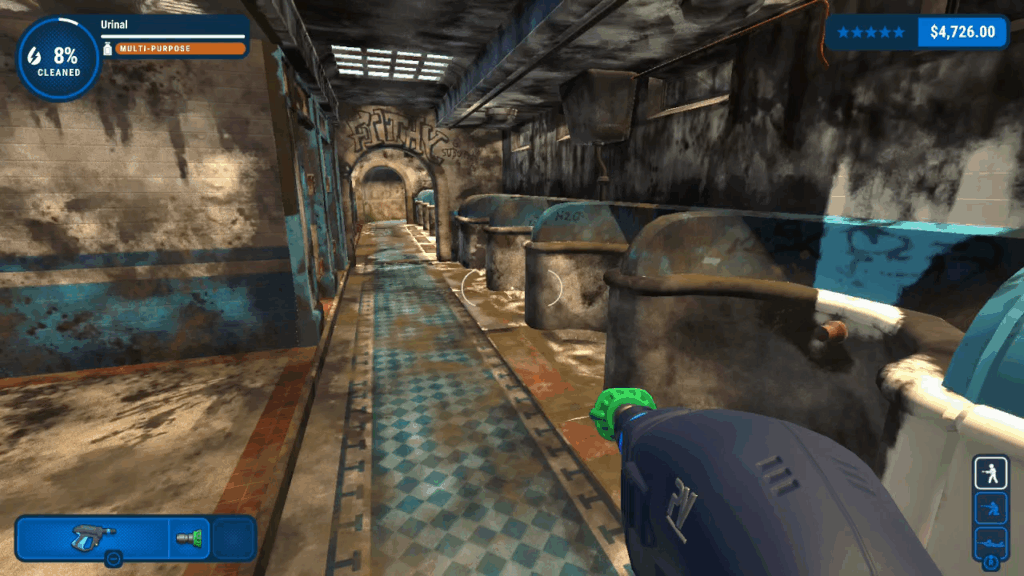

PowerWash Simulator has one of the simplest premises of any videogame I have ever described on this website: From a first-person perspective and using typical first-person shooting controls, point the player character’s pressure washer at something dirty and blast it with water until it is clean. The challenge, if it can be called that, is the scale and intricacy of the property they are charged with cleaning. Every centimeter of their current job is caked with some kind of filth. On the largest levels, the difficulty comes from cleaning vast surfaces, often including the walls, floors, and ceilings of entire buildings. For the smaller, vehicle-focused levels, the difficulty comes from all the tiny nooks and crevices that make up their decorations and machinery, requiring each component to be cleaned from every possible angle.

Many features of the interface are of great help in completing the player character’s jobs. A gauge in the top-left corner shows the current percentage of dirt that has been cleaned. Every twenty percent cleaned earns a star towards the job completion rating. It’s not necessary to earn all five stars on every job as new ones generally unlock every few stars. If I do decide to carry on to a one hundred percent clean job—and I always do—additional tools make the task easier.

With the press of a button, every dirty section of the current job is briefly highlighted in neon orange (or another color that may be chosen from the options menu). This is almost always useful to see remaining grime, though it can be difficult to make out the highlighting in a few bright, outdoor areas and on rare, similarly-colored surfaces. On a more modular level, opening the player character’s tablet lets me view a list of every object, component, or surface in the current job and see their current cleanliness level. If I select an unclean item from this list, it will flash in the environment. Similar visual problems arise with this tool, as it can sometimes be difficult to find these objects in bright conditions or if the component is especially small. Despite these minor difficulties, with a little determination and utilizing all of the provided tools, it’s feasible to clean one hundred percent of every job without wasting time re-scouring every surface for that last dot of filth.

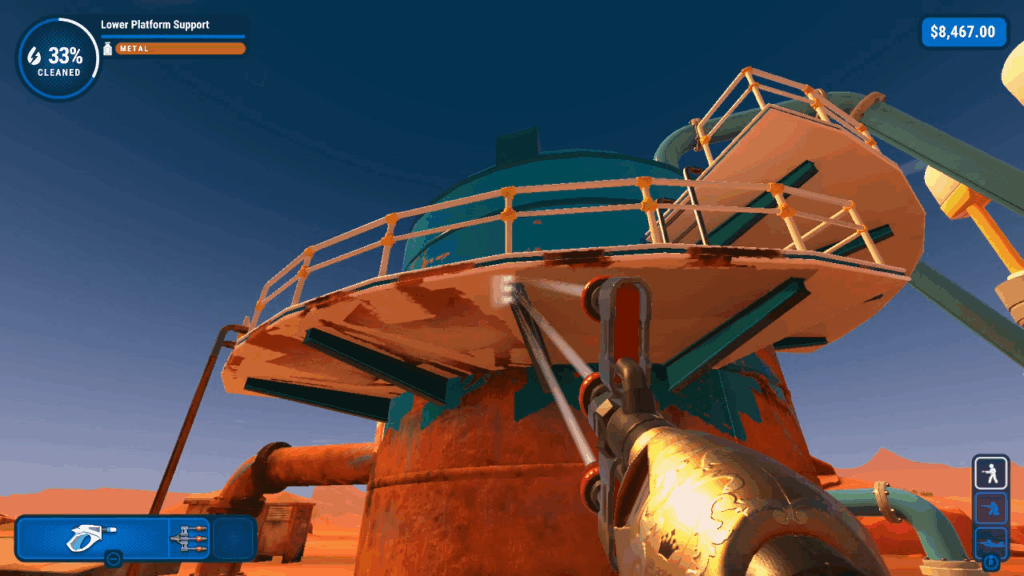

The player character’s pressure washer is an impressive tool that never feels inadequate for any of the jobs they tackle. There are four in total they may use, each purchased with the money earned from successively larger and more ambitious jobs. From the light duty Prime Vista 1500 they begin their career with to the professional duty Prime Vista Pro they wield at the end, each washer is a net gain in power, so there is no reason not to use the next-most expensive model as soon as they can afford it.

An important consideration I must keep in mind at all times is which of the pressure washer’s attachments are in use, which may be changed in an instant using a quick button press. These choices have a more dramatic impact on its cleaning ability than the improved power provided by more expensive models. Extensions to the nozzle carry the water spout further before it begins to dissipate, allowing the player character to clean high walls, ceilings, and distant decorations. All three extensions are necessary tools on most maps.

Nozzle attachments are more of a mixed bag. They change the focus of the water spout from a narrow stream of concentrated water at the smallest to a gentle wave at its widest. The narrowest nozzles see the most use as they exert enough water pressure to clean the surfaces they are pointed at. The widest, white nozzle reduces water pressure so much it’s almost useless as a cleaning tool despite the broad swath it covers. The soap nozzle is the most useless. It must be used in conjunction with expensive chemicals that eat into the player character’s profits that are better spent on pressure washer upgrades and new attachments. Soap’s ability to vaporize the most stubborn stain isn’t worth the added expense when an extra second of concentrated water gets the same result for no additional cost.

The pressure washer is a constant companion throughout the player character’s forty-plus hour adventure, giving me plenty of time to appreciate its aesthetic design. The pleasant sound of spouting water and the gentle thrum from my vibrating controller that accompany its use become familiar and comforting effects. These sensations transform what could be long and tedious work into a calming and focused experience. As jobs grow in scale, my finger begins to tire from holding down the controller’s trigger button for long periods of time. I soon learn to switch the controls in the option menu so firing the pressure washer is a toggle instead of a hold. Once I discover this trick, PowerWash Simulator transcends from a calming experience to a meditative one.

Despite its title, PowerWash Simulator does a poor job simulating our world or even the activity of power washing. A sense of unreality pervades every minute I spend in its levels. Instead of attaching their pressure washer to a cumbersome hose, the player character wears a small backpack that surely can hold just a few gallons of water; this does not stop them from firing the pressure washer as much and as long as they need to. Rust may be blasted away by untreated water, leaving behind unblemished metal underneath. There is no runoff from the cleanup job; water evaporates soon after touching a surface, carrying all absorbed filth with it. This precludes having to perform each job from the top-down, avoiding dirtying what was just cleaned, and the messy and time-consuming step of sweeping all the dirtied water away from the job site.

Even the way the player character moves feels like it’s made to convenience a fun videogame instead of an agonizing job. They must kneel or lie prone to reach all angles of their target. These poses should hinder their movement but the player character is not impaired at all. If PowerWash Simulator was not played in a first-person perspective, I would see it’s because they are not really kneeling or lying down. Instead, their torso and legs collapse into their neck like an accordion.

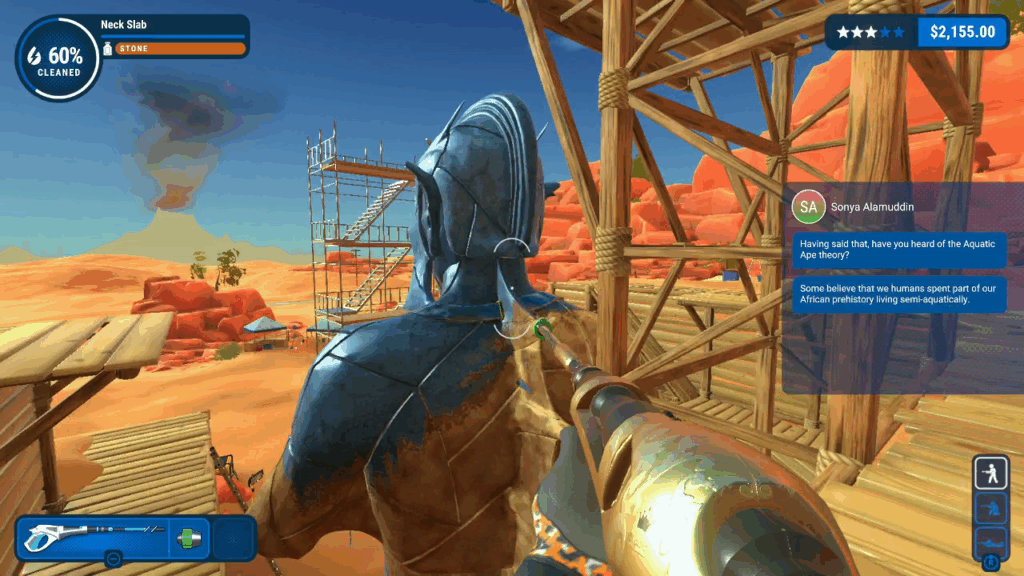

A feeling of unreality carries into the levels themselves. Apart from the grime the player character cleans from their surfaces, environments are worryingly non-reactive to their presence. The pressure washer’s immense force does not shatter windows or damage fragile surfaces. A weathervane on the roof of a forest cottage does not spin, or even bend if the player character stands on top of it. The playground’s slide is not slick. The player character can fall from the fourth floor of a firefighter’s training tower and suffer no injury. They never see another human being at any time in their job, communicating with their clients exclusively through text messages. The player character is trapped in a one-person purgatory where time has slowed, if not stopped, and the laws of physics have frozen in place. If I think about it too much, their circumstances would be terrifying. Yet all of these eerie effects are necessary. If levels were too reactive, they would be too hard and too annoying to clean. I would never finish any of them.

None of these shortcomings as a simulation matter. PowerWash Simulator’s title is wry and winkingly ironic. It knows its premise is absurd, and it knows if it truly embodied its title, it wouldn’t be much fun to play. This is acknowledged in a snooty text message that informs the player character that power washing uses hot water. Since they use unheated water, their service is pressure washing. But PowerWash Simulator is a better and less concerning title than PressureWash Simulator. From its title to the way the videogame is played, it makes repeated and purposeful choices to create an interesting and inviting videogame instead of a rigorous and accurate simulation.

I could forgive PowerWash Simulator for not having a story. I would be satisfied with a string of engrossing jobs to complete in unique locations. Surprisingly, it does have a story. All the player character’s jobs take place in and around a place called Muckingham, a distinctly English village that somehow exists on the coast of the Pacific ocean. Many of the jobs they take share at least a tangential connection. The Mayor, the comically corrupt and petty Jeff Jefferson XIII, has distracted many of the town’s services and citizens with a search for his missing cat to cover for his dealings with Blake Thrust. Blake is eventually revealed as a James Bond-style supervillain whose high-tech mining operations are upsetting the Pacific volcanic system. In the end, most of the player character’s clients come together to help them clean ancient ruins that will calm the raging volcanoes, saving the world.

It’s easy to ignore this story. It is told exclusively through the written descriptions of each job on the player character’s tablet and the text messages they receive. If I ignore these texts, the story is no less fulfilling. If I take the time to read them, I find a thin and deliberately tongue-in-cheek plot that parodies common videogame tropes. The player character, apparently by no other virtue than being the avatar through which I interact with the digital world, winds up being a chosen one who can save the world through their particular skillset. Late in the story, they are even awarded a unique nozzle that recalls the ultimate weapons bestowed upon the heroes of other, more traditional videogames at the climax or their stories. It’s a conclusion that’s just as silly as PowerWash Simulator’s premise. There’s nothing in this story to draw me in, which may be the right choice. It does exactly enough work to justify its inclusion without intruding so much that ignoring it makes the videogame difficult to understand or enjoy.

As I play PowerWash Simulator, I find myself pondering the answer to a persistent question: Why am I enjoying this? The simple premise of a pressure washing simulator should be laughably abhorrent. My willing participation in this activity seems absurd. But once I am playing, it’s difficult to stop. I spend many happy hours diligently spraying down every centimeter of 38 unique levels. Even as my hands begin to ache and my eyes become heavy while enduring the biggest and longest levels, I am unable to stop until I drive the completion meter all the way to one hundred percent. Then it takes another effort to rest before taking on the next big job.

I am probably drawn to PowerWash Simulator because it tickles many of my most troublesome traits. Nothing is more tantalizing to me than a list of objectives; I am much more likely to stay with a videogame in the long term if all of the things I may accomplish in it are presented to me in a list, the more comprehensive the better, which automatically ticks itself off as I complete its objectives. Locating every tiny component in a job, cleaning it thoroughly from every angle, and seeing the happy flash and merry ding that briefly highlights an object when it is fully cleaned is an effective Pavlovian circle. PowerWash Simulator is so engrossing to me because it overwhelms my compulsive and completionist tendencies in equal measure regardless of the mundanity of its premise.

Completing the base campaign and saving the world from a volcanic apocalypse is satisfying, but eventually the jobs run out and I wonder where I will get the next checklist of components and surfaces that require a thorough cleaning. The most immediate of these come in additional Free Play and Challenge Modes. Free Play is a no-frills revisit to any completed job which I may play with up to three other friends. Challenge Mode is more focused, limiting the player character to a specific pressure washer loadout—and often one weaker than they would have access to in the main campaign—and tasking me with finishing the level as fast as possible or using the least amount of water.

I appreciate the inclusion of these additional modes, but neither draws me in. Free Play feels redundant. Challenge Mode adds an unappealing score-chasing mandate. Completing a huge checklist on each level is appealing. Playing and replaying a level to rank high on leaderboards does not.

Much more appealing than these two rather superfluous modes is the large amount of downloadable content PowerWash Simulator has received since its release. Premium addons transport the player character to new jobs based on Warhammer 40,000, SpongeBob Squarepants, and Back to the Future, among others.

Paid downloadable content can give a favorite videogame more longevity but my real appreciation is for PowerWash Simulator’s generous amount of free content. Eight free bonus levels task the player character with cleaning the likes of a cruise ship deck, a haunted house at Halloween, and Santa’s Workshop. Themed DLC packs feature jobs set in the worlds of Tomb Raider and Final Fantasy VII, with the player character contracted to clean Shinra’s giant robot bosses, Tifa’s Seventh Heaven Bar, and the grounds of the Croft Manor. Best of all is the multi-part Muckingham Files, a new story-based set of thirteen maps, many of them as grand as the jobs the player character completed at the climax of their main quest.

Taking only the free DLC into account, PowerWash Simulator adds over 30 new levels to the default 39. With every DLC installed, an admittedly pricey proposal, it all adds up to well over 100 hours of pressure washing pseudo-simulation. I wish there were even more. I will instead have to be happy with a sequel due out by the end of the year.

Incredible though it may seem, PowerWash Simulator is one of the most satisfying and fulfilling videogames I have ever played. The care and thoroughness it demands from my efforts reminds me why I love videogames. I derive much satisfaction from methodically scratching off a long list of simple objectives, each adding up to a greater whole. This method of digging molehills into mountains is how I have learned to accomplish the successes I have in life. I hadn’t quite drawn the line between that philosophy and my lifetime of playing videogames until PowerWash Simulator illuminated it for me. For this, I will always be grateful. If a player isn’t quite as prone to compulsive behavior as I am, they may find PowerWash Simulator to be as dreadful as its premise first sounds. If they’ve ever found themselves caught by the irresistible urge to methodically complete a list of objects, they will be as enraptured as I am.