Hades II is a fast-paced isometric action videogame set in a procedurally generated underworld where a wrathful princess embarks on nightly raids to avenge her deposed family. It is set in the same underworld portrayed in the first Hades, but the comfortable status quo established in that story has been overturned. Chronos, the Titan of Time and cruel father of the current generation of ruling Olympian gods, has escaped from the void in which he was imprisoned. Swiftly deposing his son Hades and taking over the many realms of the underworld, the revived Titan besieged his remaining children in their sanctuary on Mount Olympus. The only member of the underworld’s royal family to escape Chronos is Melinoë, Hades’ infant daughter, who was smuggled away just before her grandfather’s attack. She was raised among the Unseen, a cadre of goddesses, witches, and mortal heroes who secretly operate from the unmappable forest of Erebus on the border of the underworld. For all her godly young life, Melinoë has trained as an assassin-witch with a single task and mantra: Death to Chronos.

Players experienced with the first Hades will find its sequel immediately familiar. In structure and goals, it is a broadly similar videogame. Melinoë progresses on her vengeful task by making nightly raids into the underworld, her father’s former domain, in the hopes she can reach the heart of Tartarus where Chronos has re-established his clockwork kingdom. Her task initially feels like a futile one. The inexperienced Princess of the Underworld is easily overpowered by the forces Chronos has unleashed in the underworld. Only a spell that pulls her back to the safety of the Unseen’s hidden camp when she is in peril keeps her from being killed or captured. Over many nights and many attempts, Melinoë’s power and my skill grows until together we are able to progress all the way to the depths of the underworld and dislodge Chronos from his stolen throne for the first time. But Time cannot be stopped, and the next night Melinoë must begin another raid, her struggle against her grandfather’s rule seemingly unending.

Melinoë’s mission takes her through a series of randomly generated rooms whose shape and contents are determined by which of the four regions of the underworld she is passing through. In the forest of Erebus, Melinoë follows secret Unseen routes through the endless labyrinth of branches while weaponizing the brittle trees into razor sharp shrapnel to pelt those who get in her way. The mechanical realm of Oceanus is located so deep beneath the seas even Poseidon has abandoned it, leaving its narrow corridors teeming with aquatic monsters and delicate machinery that burst forth clouds of scalding steam. Beyond Oceanus are the Fields of Mourning, an endless expanse of dead grass and bloody rocks where clouds of despair overwhelm Melinoë as she tries to dash away from swarming enemy attacks. At the end of each region, the Princess of the Underworld confronts a powerful Guardian boss, and at the end of all four regions she has a fateful encounter with the Titan of Time, her grandfather Chronos.

Experienced Hades players will likewise find it familiar to play as Melinoë as she battles through these regions. She moves swiftly, responding in an instant to the slightest gesture from the joystick. She fields two attacks, a basic Attack and an advanced Special, against Chronos’ hosts. A third face button directs her to Dash in the direction the joystick is pointed, allowing her to evade a telegraphed enemy blow or the many elemental and magical effects that frequently envelop the ground beneath her bare feet. In these ways, Melinoë is quite like the player character of the original Hades, her brother Zagreus.

It is with the rest of her abilities that Melinoë diverges sharply from her sibling. She may only Dash once. I expect Melinoë to earn additional Dashes as she expands her skillset but they never come. This feels like a response to the original Hades, where entire strategies were built around Zagreus’ ability to Dash several times in a row while stacking additional potent effects. Melinoë makes up for her limitation by more than doubling her running speed if I hold down the button after she Dashes; she doesn’t need to Dash multiple times to evade effects if she can simply outrun them. At first this change feels sacrilegious. I adapt after a few hours and come to prefer the greater mobility and sense of momentum created by Melinoë’s distinct, sprint-focused movement.

Melinoë’s final major ability is a Cast that drops a magical binding circle on the ground beneath her feet. Common enemies caught in the Cast are nearly immobilized while inside the circle. The first real learning curve I must overcome is developing the habit of exploiting the Cast to keep Melinoë safe, using it to keep crowds of enemies under control then either attacking them from a distance or rushing in to deal precise blows before rushing back out. There may only be one Cast active at a time, but Melinoë may drop another as soon as the previous one expires. This ability, more than any other, emphasizes Melinoë’s role as an agile trickster witch in comparison to her brother, the swift and brutal warrior.

The final trick in Melinoë’s toolset is the one that makes Hades II feel the most different from its predecessor. Attacks, Specials, and Casts may be charged into an Omega form by pressing and holding the associated face button. The Omega forms of the Attack and Special become bigger and more powerful versions of themselves. The Omega Cast has the most impactful new effect, causing damage to enemies caught within the binding circle in addition to the slowdown.

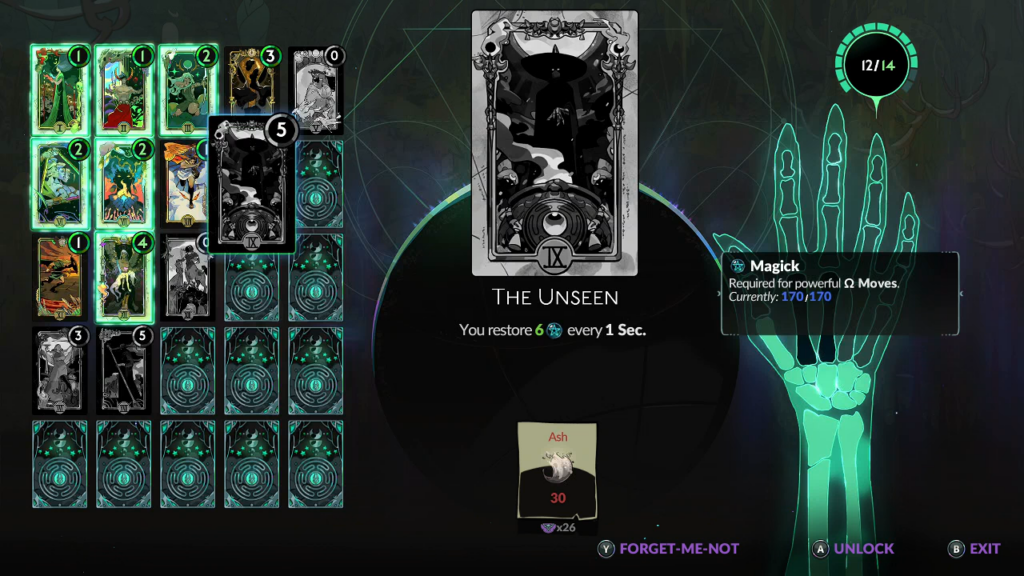

Omega moves are powerful additions to Melinoë’s toolset but they carry additional risks and requirements. Each takes a moment to charge to its full power, during which Melinoë is motionless or has a significantly reduced movement speed, leaving her vulnerable to enemy attacks. It takes me some practice and effort to remember to charge her Omega moves in response to an enemy’s attack instead of pre-empting it. A more significant limiter is Melinoë’s Magick resource. Each Omega move requires a certain amount of Magick. If the Magick gauge is empty, Melinoë cannot empower any more Omega abilities until she finds a way to restore it. In the first few runs these options feel hopelessly limited; the only guaranteed way to earn a refill is to enter a new room, which instantly replenishes the gauge. Over time, as I learn the significant depths of Hades II’s complexity, I find that there are innumerable ways to restore Melinoë’s Magick even in the heat of combat. Under the right conditions, she functionally never runs out.

These movement, offensive, and crowd control abilities are the baseline at which Melinoë operates. She always has access to them. Her performance may be further tuned as she progresses on a run depending on the choices I make for her. The most significant of these choices are made before Melinoë even leaves the safety of her sanctuary. A small clearing serves as a meditation space where she may train and prepare for her next attempt to assassinate her usurperous grandfather.

Beneath a stone arch, Melinoë may outfit herself with a hand of Arcana cards. Each Arcana has a different effect on her abilities. Improved numbers for her starting Health and Magick pools. An increase to her damage when attacking enemies under special conditions. Slowing enemies around Melinoë while she charges Omega moves. Extra chances to keep fighting when Melinoë’s Health pool depletes. Every Arcana is potentially invaluable but only a small number may be equipped at once. The number of Arcana Melinoë has access to, their level of quality, and the total she may equip at once may all be increased using resources she gathers in the underworld. This is where Melinoë’s growing power is most felt early on. Her first successful defeat of Chronos is likely to coincide with purchasing, enhancing, and equipping some of the most useful Arcana before she begins that night’s attempt.

The other major choice that impacts Melinoë’s performance is which of the Nocturnal Arms she equips. Each is a different legendary weapon that was once, or someday will be, wielded by a godly figure significant to the mortal world. Each Nocturnal Arm has distinct Attack and Special functions that change up how Melinoë plays. Some are predictable. The Moonstone Axe has slow, hard-hitting attacks with impressive range. The Sister Blades contrast the Axe with limited range and damage but make up for it with the fastest attack speed of all weapons. Other weapons are more mechanically unusual. The Umbral Flames are a purely ranged weapon, letting Melinoë bombard enemies from a distance with continuous damage from two different projectiles. Melinoë wields the Argent Skull by hurling it at enemies, but she may only carry a small number of Skulls at once and must run and pick them up before she may hurl them again. Even the Witch’s Staff, Melinoë’s default weapon, is unusual in combining a fast and weak melee attack with a slow and slightly more powerful ranged one.

It’s how the Nocturnal Arms distinguish themselves under the effects of Omega Moves where they show their true diversity. I expect the Moonstone Axe to be the weapon of a brutal Melinoë who relies on getting in her enemies’ faces and dealing crushing, single blows to defeat them—and under the right conditions it does excel with this approach. Alternatively, Melinoë may rely on its Omega Special attack that creates a wide shockwave across the entire battlefield. With enough skill and preparation, it’s entirely possible to exploit this attack to transform the Moonstone Axe into an impromptu ranged weapon. Many of the six Nocturnal Arms have their already-unorthodox attacking methods further specialized by the unique effects of their Omega forms in this way and may be further specialized with additional upgrades and customizations.

The remaining adjustments made to Melinoë’s performance are earned over the course of her next run through the underworld. The goal in most individual rooms is to defeat all of Chronos’ servants that guard it. When this task is completed, Melinoë earns a reward. Centaur Hearts increase her Health pool. Soul Tonics increase her Magick pool. Hammers left by the mortal craftsman Daedalus imbue her Nocturnal Arm with new or modified attributes. These rewards are essential, empowering Melinoë so she may survive the harder challenges she faces as she nears her grandfather’s throne. They are also transient, disappearing at the end of her current run when she is recalled to the Crossroads.

The most important of these impermanent rewards are the Boons. When Melinoë touches one, she is connected with one of her extended family in their sanctuary on Mount Olympus and gifted with a powerup to one of her abilities. Each Olympian’s Boons specialize in a particular effect or playstyle. Zeus causes thunderclouds to appear over enemies heads when they are struck, which will eventually drop a lightning bolt down on them for extra damage. Hera curses enemies with a mark that causes them all to take shared damage, letting Melinoë casually mark a crowd then decimate them with sustained damage against a single target. Hephaestus adds colossal blows from his blacksmith’s hammer to attacks whose sheer power is offset by the long cooldown before the effect will happen again.

Boons will be familiar to players of the original Hades as the system is faithfully reproduced here. The most obvious changes are some fine tuning and redesign brought to effects from certain Boons; Athena and Poseidon no longer have the runaway-best Boons to choose for any run, and Boons as a whole feel much better balanced. Once again, Hades II distinguishes itself through increased complexity. There are many more Gods and Goddesses to offer Boons to Melinoë, and with the unique properties of the Cast, the addition of Omega moves, and a Magick recovery option unique to each Olympian, there are many more effects for their Boons to take.

Melinoë is rarely put in a place where a poor selection of randomized Boons cripples her potential early on. With enough practice and patience, any combination of Boons will be effective. Yet some Boons are still more effective with certain Nocturnal Arms. The rapid-fire damage from the Sister Blades match best with the critical damage bonuses from Artemis and the raw damage boosts provided by Aphrodite and Ares. The Moonstone Axe already has impressive reach but combine it with Apollo’s Boons that increase the area effect from Melinoë’s attacks, and a few upgrades can have a single axe swing envelop most of the screen. I don’t really become successful in Hades II until I learn to recognize which Boons synergize best with which Arms and deliberately lean into choosing them among Melinoë’s randomized rewards.

After each of Melinoë’s raids on the underworld, successful or unsuccessful, she is teleported to the Crossroads, a hidden camp in Erebus and the home base of the mysterious Unseen. It is a place of safety, invisible to Chronos and his forces, where Melinoë may rest and decompress before beginning her next run.

The most important activity in the Crossroads is interacting with the other members of the Unseen and the various guests and refugees they allow into their protected encampment. Their leader is Hecate, Olympian mythology’s most powerful witch, who was the one charged with raising Melinoë and training her for Chronos’ defeat. As the story begins, the pair have an interesting dynamic of a recently graduated student slowly being accepted as an equal by her mentor. Melinoë’s progress on her quest may be marked in step with her growing familiarity with her former headmistress.

Most of Melinoë’s other relationships are similarly stressed by difficulty, conflict, and change. Her best friend and confidant is Dora, an ancient mortal shade who alternates between dour advice and taunting threats. Dora’s mood swings are miserable attempts at comedy, but I believe they are meant to portray a character with a terrible sense of humor, and Melinoë takes it in her stride. A new visitor to camp is Moros, the Fates’ messenger whose lonely existence was broken only by deliveries of the worst news to humanity. It takes a long time for Melinoë to break through Moros’ reserved personality and get to know the tenderhearted man beneath. About the only uncomplicated relationship Melinoë has is with the hero Odysseus, who is never anything but polite and courteous to the goddess; perhaps he learned a lesson about angering the gods during his mortal life.

Speaking with Hades II’s supporting cast is the primary way to progress its narrative. Every time Melinoë encounters a supporting character, be it in the Crossroads, encountered at random while exploring the underworld, or even when accepting a Boon from an Olympian during a run, they will have something new to say. This tidbit of information will either progress the greater story of the struggle against Chronos, develop the personal relationship between Melinoë and supporting character, or fill in more of their personal backstory. There are hundreds of individual dialog exchanges between all thirty-three characters to witness and every single one is fully voiced by a talented cast of actors. Even after more than one hundred hours of playing Melinoë still encounters characters with new things to say.

This incremental approach to storytelling and character development is what the first Hades did best, and it returns here without much expansion. Even an unsuccessful run in the underworld can still be an enticing prospect because it gives Melinoë an opportunity to further deepen her relationship with her friends and family and learn new details from them. Progress is gated only slightly by gifts which must be given to each character to build their relationship meter. Some dialog will never appear until Melinoë gives enough Nectar to a person. The ease with which these gifts may be earned—plenty of gifts are found as rewards during underworld runs, and more may be purchased in town at a cheap price—masks the feeling that this is all one giant grind. In all my time playing Hades II, I cannot recall a single instance when I really wanted Melinoë to give a character a gift and she didn’t already have one close at hand.

The centerpiece of the Crossroads is a massive cauldron. By using reagents to complete Incantations in this device, Melinoë accesses improvements that benefit her on every subsequent visit to the underworld. Reagents are gathered during Melinoë’s visits to each region of the underworld. Here again Hades II reveals its increased complexity over its predecessor. In the first Hades, Zagreus collects seven different resources to increase his power and expand the size of the playable world. By significant contrast, Melinoë must amass dozens of different reagents, including varieties of flowers and minerals exclusive to each region, and seeds grown in a small farm plot tucked into a corner of the Crossroads.

This system for unlocking new features has a real impact on the pace at which Melinoë, the Crossroads, and the underworld grows. Because specific reagents are needed to activate certain Incantations, Melinoë has to proactively work towards unlocking the next one by purposefully seeking out missing materials. Luckily, Incantations (and other unlocks) may be bookmarked, highlighting places where needed reagents appear during her next visit to the underworld. This minimizes the possibility of missing them, expediting the labor of finishing that next, vital Incantation. Even with the aid of these bookmarks, Melinoë can still go several nights not finding a reagent she needs because it simply doesn’t appear. This creates a disconcerting sensation of standing still despite putting in hours of effort across multiple runs, a feeling I almost never experience in the first Hades.

The cauldron is not the only source of improvement for Melinoë found in the Crossroads. Different collectables allow her to expand, improve, and equip more Arcana, purchase and upgrade new Nocturnal Arms, improve the benefits offered by animal Familiars that join Melinoë on her nightly raids, and even make purely cosmetic changes to the Crossroads. The number of items to keep track of quickly becomes overwhelming. Even after Melinoë unlocks most of the Crossroads’ bounties, it’s easy to forget to purchase or improve at least one thing before sending her off on another attempt on her grandfather’s life.

A trademark feature in Supergiant-developed videogames is the option to replay their campaigns with special modifiers applied to specific aspects of the scenario. This familiar feature returns in Hades II as the Testament of Night and is earned the first time Melinoë defeats Chronos. By toggling oaths at the Testament before starting a new run, Melinoë may granularly increase the amount of damage enemies absorb or dish out, reduce the number of upgrades presented to her by her cousins’ Boons, place a hard limit on how much time she may spend in each region, and many other factors. The more Oaths Melinoë accepts before beginning a new run, the more difficult it will be.

The most impactful Oaths are Fangs and Rivals. The Fangs oath adds additional modifiers to some enemies, essentially adding a new layer of randomness for Melinoë to overcome in each room. The Rivals Oath upgrades each region’s Guardian boss into a new Unrivaled variant. Unrivaled Guardians move even more quickly than their regular forms, add additional bodies to their fight, and fill their arenas with dizzying arrays of damaging fields, projectiles, and obstacles. They make the enhanced bosses that appear in the first Hades look like the easy mode in a videogame for preschoolers. If Melinoë doesn’t wield as many powerful and synergizing Boons from her cousins as possible, Unrivaled Guardians are next-to-impossible to defeat.

The real purpose of accepting Oaths is to build the level of Fear that fills the underworld that night. Each Oath taken adds at least one point of Fear. If Melinoë builds the Fear value high enough, she may accept bounties to defeat certain Guardians while wielding certain Nocturnal Arms. Finishing these bounties earns Melinoë Nightmare, Hades II’s rarest and most valuable resource that upgrades the power of the Nocturnal Arms. For every bounty she finishes, the amount of Fear needed for the next one rises. As Melinoë finishes more and more of these bounties, I start to realize that it is not the heroine who experiences these high levels of Fear. It is her enemies, who continue to fail even as their advantages grow. Melinoë is never granted the title, but I begin to regard her as the Goddess of Fear by the end of her story.

The strength of a procedurally generated videogame is dependent in large part on how well it entices me to keep playing, particularly after I have successfully reached the end of its campaign and conquered its final boss. I criticized the original Hades in my review for offering few surprises; Zagreus always visits the same locations in the same order even as his number of successful escapes grows into the hundreds and he reaches the limits of the Pact of Punishment, his equivalent to the Testament of Night. Hades II seemingly suffers the same fate until it pulls a surprise from behind its back: An entire second campaign.

Hades II’s second campaign should not be taken for granted. It’s as fully featured as its first, sending Melinoë through four new regions filled with new enemies, reagents, and supporting characters. It all culminates in a titanic boss fight even more epic and challenging than Melinoë’s battles with Chronos. To keep things fresh, the second campaign thoughtfully remixes how rewards are earned. The first region allows Melinoë to pursue which rewards she wishes from a preset group instead of choosing between two doors with randomized rewards behind them. The next region is structured more like the spaces in the first campaign but provides opportunities for Melinoë to earn multiple rewards in a single room. Small gestures like these keep Hades II fresh and breathe new life into it just when Melinoë’s struggles through the underworld begin to feel predictable.

At every step of the first Hades’ narrative, Zagreus’ reasoning for nightly escape attempts from his father’s realm makes sense. I understand the purpose of continued runs through its procedurally generated dungeon long after its protagonist’s original motivation has been resolved and discarded. It is a genius synthesis of narrative and videogame design. By contrast, the reasoning for Melinoë to continue her nightly assaults on the underworld after her story’s conflict has been resolved feels obligatory. The narrative justification is contrived. She must do it because a procedurally generated dungeon crawler requires her to continue her raids in perpetuity. Nothing disappoints me more about Hades II than my inability to be as complimentary about its narrative devices as I am towards its predecessor.

Supergiant openly workshopped the conclusion to Hades II’s narrative during its open access period, reworking and tweaking events and characters’ responses to them based on player feedback. I understand the reasoning behind many of the changes made during this process. Melinoë was originally a virtual non-participant in her narrative’s resolution. In the touched-up ending, she is more of a proactive contributor to the found solution, though with the result of a change in attitude towards her circumstances that feels sudden and unearned. Melinoë chooses to remain in the Crossroads and continue endlessly hunting her grandfather instead of rejoining the family she has struggled for literally her entire life to free. The only sign that anything has changed is a portrait hung in Melinoë’s tent, depicting the grown Princess posing happily with her royal family. It is a lie. This never happens. She has never known them, and apparently never will.

This feedback-based approach to developing the narrative, and particularly its convoluted justification for Melinoë’s neverending attempts to assassinate her grandfather, stinks of a story written by committee. Seemingly in an effort to dissatisfy the least number of players, no firm justification is made for anything that happens as a result of the narrative’s conclusion. Almost everyone around Melinoë questions why she chooses to stay in the Crossroads instead of indulging in the outcomes of her efforts. She has no satisfactory response because there is no satisfactory response. Zagreus chooses to stay in the House of Hades because it is the natural conclusion to his character arc. Melinoë remains in the Crossroads in spite of it not being the natural conclusion to hers because the scenario demands she do so. Hades II’s narrative is out of sync with its scenario.

After reaching this first ending, Melinoë may continue on through many more hours and many dozens more runs through both campaigns to reach a second ending. The outcome here is even less satisfying. Most of the cast is not involved emotionally or practically in the stakes of the second ending; when given the chance to comment on its outcome, most of the Olympian and Chthonic gods even dismiss it as unlikely or irrelevant. Few seem to care about what is happening, which in turn makes it difficult for me to care. It all occurs offscreen and potentially hundreds or even thousands of years in the future. I have no choice but to take the narrative’s word that it happens at all. It has no impact on Melinoë, her family and friends, or their present situation. I continue playing Hades II long past its second ending and one hundred hours of playtime because it is fantastic on a mechanical level. Its story taken as a whole is a dud.

I am unable to disentangle Hades and Hades II from each other in my critical appraisal of both. There are times when I will prefer the first Hades’ mechanical simplicity and narrative intricacy. At others I will appreciate Hades II’s greater systemic complexity and grander scope even though its story disappoints. My suggestion to all is to play Hades first, then continue on to its sequel if you’re still interested. Which is the overall better videogame is a tedious and irrelevant discussion. It’s much more important to recognize that the weaknesses of one put the strengths of the other in an even greater light. Both are incredible videogames who complement each other well. If one must be weighed against the other, I would say that the first has greater precedence and will have more long-lasting resonance. This does not mean the second is worse or a waste of time, merely less urgent and less immediately iconic. Fans of action videogames, dungeon crawlers, and family drama narratives driven by strong characters should make time for both. Since I suspect most of these people have already played the first Hades, there is no reason not to play the second. It is a marvelous sequel.