Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 is a lavishly produced roleplaying videogame that combines elements of traditional, turn-based RPGs with fresher ideas that dominate the new school of action RPGs, particularly those popularized by FromSoftware’s inescapable Dark Souls series. The story begins in the island city of Lumière, which 67 years previously was separated from the mainland by an event known as The Fracture. With The Fracture came the arrival of The Paintress, a giant who appears once a year to paint a number on The Monolith, a mountain face visible from Lumière’s shores. Beginning at 100 and counting down by one every year, anyone older than The Paintress’ scrawled number experiences the Gommage, in which their body dissolves into a shower of rose petals. Since the yearly culling will reduce the population to only children in less than two decades, the extinction of Lumière’s people feels imminent and inevitable.

Lumière’s survivors do not idly wait for their extermination. Once a year, shortly after the Gommage, they send out an expedition whose goal is to reach The Paintress and put a stop to her countdown. None of the previous expeditions have been heard from again. Expeditions are numbered after the year The Paintress draws on The Monolith, and this year’s group is Expedition 33. Their mission is an immediate disaster. As soon as they make landfall on the continent nearest to Lumière, Expedition 33 is overrun and slaughtered by grotesque monsters called Nevrons, led by a wrinkled, gray-haired man—a man who should have Gommaged decades ago. With only four survivors left of the dozens who first set out from Lumière, Expedition 33 must pull themselves together and explore a bizarre world of fine artwork brought to life, seeking to overcome the mysterious old man, find and confront The Paintress, and put a stop to the cruel cycle of death.

Clair Obscur’s world is a painting. I do not believe this is meant to be a revelation. The evidence is there from the beginning. The first image I see is a structure resembling a dissolved Eiffel Tower, as though an unhappy artist dashed paint thinner across a failed piece they wanted to destroy, trapping a visage of the tower dripping off the overturned canvas forever in time. Similar scars of melted terrain are found all across the world.

As Expedition 33 explores beyond Lumière’s shores, they encounter more sights and figures that seem like artwork come to life. One early area is Flying Waters, an aquatic environment complete with barnacle beds, plants swaying with the underwater tides, and whales swimming overhead. Expedition 33 is able to travel through it because it is devoid of actual water. Another area, Sirène, is a massive colosseum made from rosy stone and draped fabric; it’s as much a cloth sculpture as a building, and the delicate Nevrons inside dangle and spin like dancing marionettes guided by strings from an invisible puppeteer. Another of the world’s prominent races are the Gestrals, artist’s manikins whose featureless bodies are brought to life as boisterous, childish scrappers and decorated with faux-tribal markings. Expedition 33 themselves seem aware of the nature of their existence. A frequent battlecry is not “let’s shed some blood,” it’s “let’s shed some paint!”

Once it settles in that this is a painted world filled with painted people, I begin to question Clair Obscur’s visual design. If this is all an artist’s creation on a canvas, why does it have the distinctive faux-photorealistic appearance of a contemporary videogame? Do I see its world as “real” because its painted protagonists see it as real? Perhaps the title hides a clue. From French to English, Clair means Clear and Obscur means Hidden, a contradictory duality that reflects the lifelike visuals found in this painted world. Expedition 33 is certainly mortal; they suffer frequent losses across the story and often enter cutscenes smeared with blood from their most recent battle. But is it blood, or is it paint? There seems to be no satisfactory answer. Maybe there is no answer at all and I am only meant to ponder the question. The answer is both clear and hidden.

Or maybe the answer is cynical. Maybe Clair Obscur visually defies its own setting because it wants to punch above its weight by looking like a Final Fantasy videogame. If this is the reason, I am disappointed. It looks great in screenshots, but once I begin playing, I can see its limitations. Distant waterfalls pour from nothing and disappear into nothing. Characters’ clothes and hair often clip through their limbs and torsos as they move. When Expedition 33 makes camp, their site is always on the same cliff overlooking The Monolith, regardless of where they actually are in the world. These details are small compared to the wonderful facial animations and a beautiful lighting system, but as I am called to question why Clair Obscur looks the way it does, these budgetary shortcomings become more difficult to overlook without comment.

Aside from its AAA-adjacent visuals, Clair Obscur’s most attractive attribute is its combat systems. Nevrons wander the world and chase the current party leader when they are seen. If the Nevrons make contact with the party or the party leader is able to land a First Strike with a burst of energy from their hand, the perspective shifts to a familiar RPG battlefield where both groups face each other across an invisible line.

At first, battles seem to be a straightforward imagining of how they unfold in a traditional, turn-based RPG. Party members and Nevrons take turns to attack each other. Every party member always has a basic attack available to them. Their advanced abilities are limited by their Action Points. They generate one each turn, which feels quite limiting to start out but they soon access ways to create many more.

Action Points may be spent in two ways. The first is to use a character’s Skills, powerful abilities that deal damage, empower the party, or disempower the enemy—and as the Expedition grows more powerful, frequently all three at once. Skill animations are accompanied by fast on-screen button prompts and successfully inputting them increases the Skill’s power or potency.

Action Points may also be used to fire a character’s ranged weapon. These are manually aimed using an over-the-shoulder perspective familiar from third-person shooters. Many Nevrons have minute weak points that take additional damage from projectile attacks. Interestingly, the number of shots a character may fire each turn is limited only by their available AP. If I want to have them expend all their AP every turn firing projectiles, I may do so.

When Nevrons attack, Clair Obscur remains highly interactable. Enemy attacks may be dodged, jumped over, or reflected with two distinct kinds of parries. Dodges have wider windows of opportunity than parries, creating a tradeoff between risk and reward. Parrying a Nevron’s attack opens them to a devastating counterattack, but missing the timing can be just as harmful to Expedition 33.

Nevrons come in all shapes and sizes. Some will claw at the party with their hands. Others carry long swords they swing and thrust in elaborate combos. A few are giants who use their bulk to crush their enemies or overwhelm them with shockwaves. Most Nevron varieties recur across the entire campaign and there are only a few dozen in total. While this does make Clair Obscur’s bestiary feel limited, it also lets me become familiar with their attack patterns, learning to dodge and parry with exact timing through rote exercise. This is mandatory for success, as even the hardiest party member will quickly succumb to just a few successful hits from a hostile Nevron.

These serviceable and familiar combat systems are elevated by the party members that make up Expedition 33. Each one has distinct mechanics that take practice and effort before I learn to use them to their full effectiveness. For this reason, I cannot be complacent about which party members I use. If Expedition members I have relied on suddenly become unavailable—and this happens multiple times—then I can be in a bad situation when forced to use another character whose mechanics I have not learned to use effectively.

Gustave is the simplest and most straightforward Expedition member, and fittingly the first one I gain control over. His engineering genius manifests in the form of his prosthetic arm, which accumulates electrical charges from many of his abilities. The more charges Gustave can stockpile, the more powerful an attack he unleashes with it. Gustave’s partner in invention is Lune, a mage who generates elemental Stains whenever she casts a spell. Stains increase the effects of her other spells and are expunged upon use, encouraging a strategic roulette of all her abilities instead of abusing only her most powerful spells. Maelle may be the youngest member of Expedition 33, but she is also its most accomplished swordswoman. Every time she uses a skill, she shifts between stances that affect the damage she takes and enhances one of her other skills. Similarly to Lune, this encourages chaining her skills together to create powerful outcomes instead of relying on her most expensive skill.

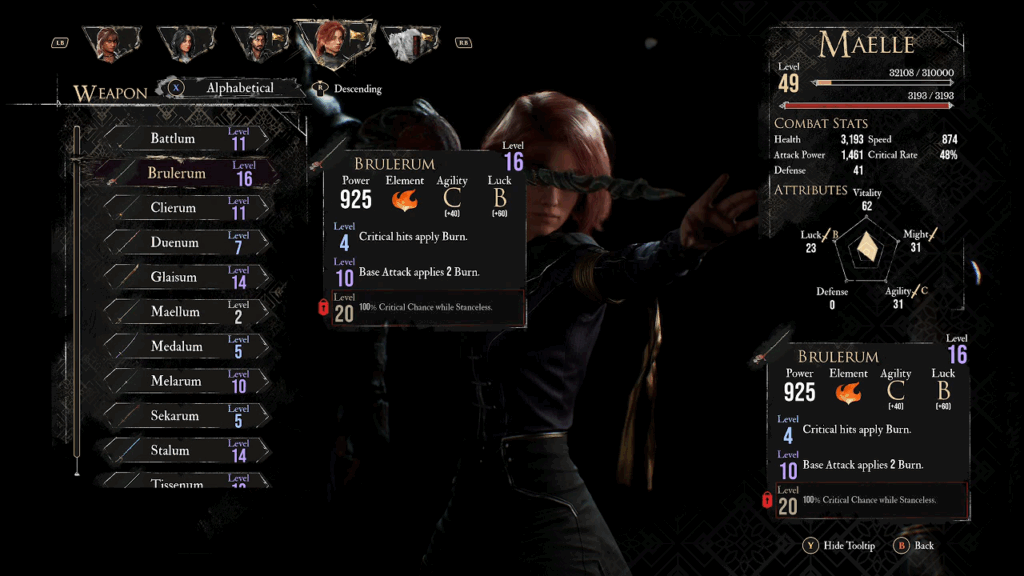

A character’s individual skills can be further enhanced by how they are equipped. I found Maelle to be the backbone of my party, so she has several good examples.

Weapon drops are frequent and they come with attributes that can completely change up party strategy. One of Maelle’s weapons heals the party each time she enters Virtuose Stance and casts a defensive buff when she leaves it, encouraging a skill loadout that lets her frequently leave and re-enter that state. For a more damage-focused build, another of her weapons doubles the number of Burn debuffs her abilities place on enemies and increases the damage they deal, encouraging a build loaded with her most fiery attacks.

Pictos are the other half of developing characters with a powerful strategy. Instead of armor, equipment-based boosts to a character’s RPG statistics are provided by Pictos. These numbers are incidental. I never equip a single Pictos to an Expedition member purely for the statistical benefit. It is each Pictos’ Lumina effect that is the real reason to seek out and equip them.

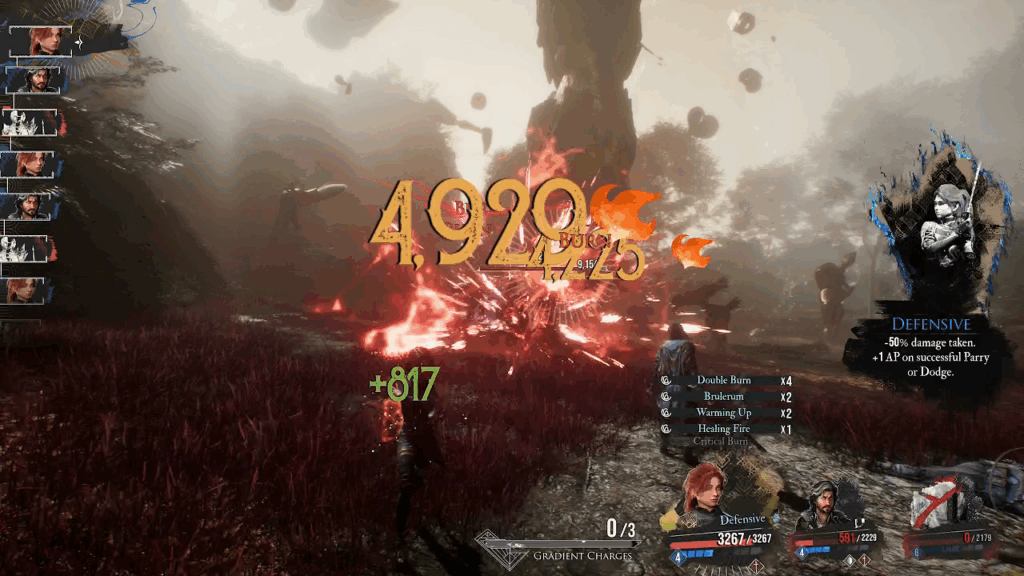

Lumina passively enhance a character’s skills when they are equipped. When equipped with the right sword and skills, Maelle is already a fearsome fire-based fighter, able to apply Burns to her enemies that damage them every time they get a turn in combat. Her effectiveness may be further enhanced with Lumina that double the number of Burn stacks she applies, increase the number of turns Burn affects the target, heals the party each time an enemy takes damage from a Burn, increases all damage dealt to a Burned target, increases the chance a critical hit will be dealt to a Burned target, and generates Action Points each time a Burn is applied. All of these Lumina may be equipped simultaneously.

With the right loadout of Skills, weapon, Pictos, and Lumina, Maelle can blaze her way across Clair Obscur’s world as a one-woman army. Her Burn damage can be built to such heights that even fire-resistant enemies barely slow her down. And this is just one of many possible strategies to employ. Clair Obscur is one of those RPGs where it’s fun to find the myriad ways its systems can be broken by exploiting available tools. There are some Nevrons who are immune to certain effects and Expedition members occasionally become unavailable during the plot, so finding more than one viable strategy is advisable. Building an entire team of broken Expedition members is a joyous activity.

There are some limitations to these systems. Only three Pictos may be equipped at a time, so characters only ever benefit from three Lumina from those sources. To equip more, Lumina may be learned from Pictos by equipping them on a party member in four battles. Once a Lumina is learned, they may be equipped to any other party member without a Pictos.

Equipping Lumina by this method is limited by the character’s Lumina Points. They earn a few points every time they gain an experience level, but this will only give them a few dozen total by the end of the story. The best Lumina can require as many as 40 Lumina Points to equip. To increase the party’s Lumina Points, they can use an item called the Colour of Lumina. The main reason to thoroughly explore every area of the world is to find these items, which are found stashed in almost every corner and closet. A player struggling with Clair Obscur probably hasn’t spent enough time pursuing Pictos and using Colour of Lumina to enhance their party.

The final element affecting a character’s battle performance are their Attributes. Weapon damage scales based on one of five character stats: Health, Attack Power, Speed, Defense, and Critical Rate. A weapon with an A in Speed damage scaling will deal more damage in the hands of an Expedition member with points invested in Speed than one without. The temptation created by this system is to invest every level up point into a weapon’s favored Attributes and put the rest into Health. I try this for a while early in my time with Clair Obscur, to mixed results.

The twist to these systems is that even if they are not scaling their weapon damage, none of a character’s Attributes are truly useless. I can get away with only putting points into health and a damage Attribute early on. If that damage Attribute isn’t Speed, it soon happens that Nevrons get up to a half-dozen turns in a row before my damage-specced Expedition member gets even one. They will likely kill the Nevron in one hit during that turn, but then they have to survive six more turns before they can attack again. Attack Power is the catch-all. I do not encounter a single weapon that scales off Attack Power, but this is not a bad thing. It makes that Attribute equally useful to all characters, allowing them to boost damage with all weapon types instead of just the ones that specialize in a particular type of scaling. Clair Obscur’s Attribute systems are made with intention, deliberately cutting off this player’s tendency to min-max my way to success.

I have some hope for Clair Obscur’s many areas when I first encounter them. Spring Meadows, the first proper area Expedition 33 explores, follows a zig-zagging path through a canyon filled with water and greenery. It soon becomes apparent that zig-zagging is all it does, and it sets the model for almost every subsequent area. They follow a single linear route. There are a few paths that shoot off from the main one, but they quickly deadend on a Colour of Lumina, a Pictos, or some other pickup, and the party must backtrack to the main path to continue on. Levels have scale but not intricacy. They are uninteresting to explore.

Actually navigating each level becomes a pain. Colors and objects repeat themselves across every area, blending together into a mass of sameness. In many areas, Expedition 33 wanders back and forth across the same space repeatedly because I cannot tell from their surroundings that they’ve already been there. Navigating levels is difficult because I often can’t tell where Expedition 33 can go, where they’re supposed to go, and where they’ve already been. A minimap could alleviate this problem and there’s no good reason for its absence. Areas are not large or intricate enough for a minimap to betray their secrets. Most areas do not have secrets. The party is kept in these level boundaries by a mashup of random barriers. It’s disorienting first encountering an invisible wall, then around the next corner a pit the party can freely fall into, then around the next a steep rock face or an inexplicably solid thicket of trees.

When Expedition 33 first leaves Spring Meadows and enters the world map for the first time, I am intimidated by its scale. Swirling portals lead to dozens of areas spread across the map. I soon learn this apparent scale is an illusion. The main story follows a straight line directly across the map from Lumière to The Paintress’ Monolith through a small number of areas. Most of the dozens of side areas they pass on the way consist of a small circular space, usually a cave, meadow, or ruin, with a single NPC inside. Many areas are a static location, the camera locked at a distant perspective to keep Expedition 33 from exploring them in detail. They contain an item to pick up—usually a record that may be played on a record player in camp—and nothing else. These areas have a landscape-like quality, leaning into Clair Obscur’s fine art theme, but they are not interesting to explore. When I finally find one of the few optional areas that contains an explorable space, discoverable bonus items, and a challenging optional boss encounter, it’s an elating moment. I wish Clair Obscur’s world elated more often than it does.

These few side areas contain some of Clair Obscur’s most frustrating activities. Many contain pure white Nevrons, docile and apparently amnesiac creatures who request that Expedition 33 deliver them an item found somewhere else in the world. There’s no element in the interface to track these fetch quests, leaving me with annoying questions. Who wanted this item? Where are they? How do I tell them apart from every other NPC with nothing to say? I do my best to check in with everyone before credits roll but I do not worry about any I may miss. Clair Obscur does not treat them with any importance.

The most infuriating side areas are the multiple Gestral Beaches. These are gigantic open spaces, suggesting they were meant to contain much more than they do. What they do contain is a single friendly Gestral who presents Expedition 33 with a platforming challenge. Clair Obscur is not designed for platforming, so completing these challenges is a miserable experience. Thankfully, all they reward is Victorian-style swimsuits for the party. I do not feel disappointed that Expedition 33 misses the chance to wear them.

I admire Clair Obscur’s combat systems and am disappointed by its level design. Where it challenges me is in its plots, characters, and themes. It goes many places I do not expect and ends with a moral I’m not sure wholly works.

The premise is compelling. At its outset, Clair Obscur approaches the timely topic of a generation’s despair at what feels like their inevitable extinction. Post-apocalypses have been frequent settings in all forms of media these past few decades as our collective unconscious has descended into darker and more nihilistic places. Clair Obscur makes the novel choice to set its story in an apocalypse as it is happening. It is slow, excruciating, and traumatic to all trapped inside. Expedition 33’s quest is based in hope for the future even as its characters feel hopeless against everything they have endured. At just sixteen years old, Maelle is the focal point of these ideas. She is terrified at what’s coming within her lifetime, furious that preceding generations have been unable to stop it, and desperate to do what she can to help. Clair Obscur has the most relevant plotline in recent memory.

As Expedition 33 explores the continents beyond Lumière, they find signs of another conflict juxtaposed to their own. In many surprising places they find out-of-place regal wooden doors that all lead to the same manor’s interior. The space is eerie, well-kept, warm, and friendly, but devoid of any life. If I examine the portraits and journal entries Expedition 33 discovers during their visits to this extradimensional manor, I slowly assemble a picture of what happened there.

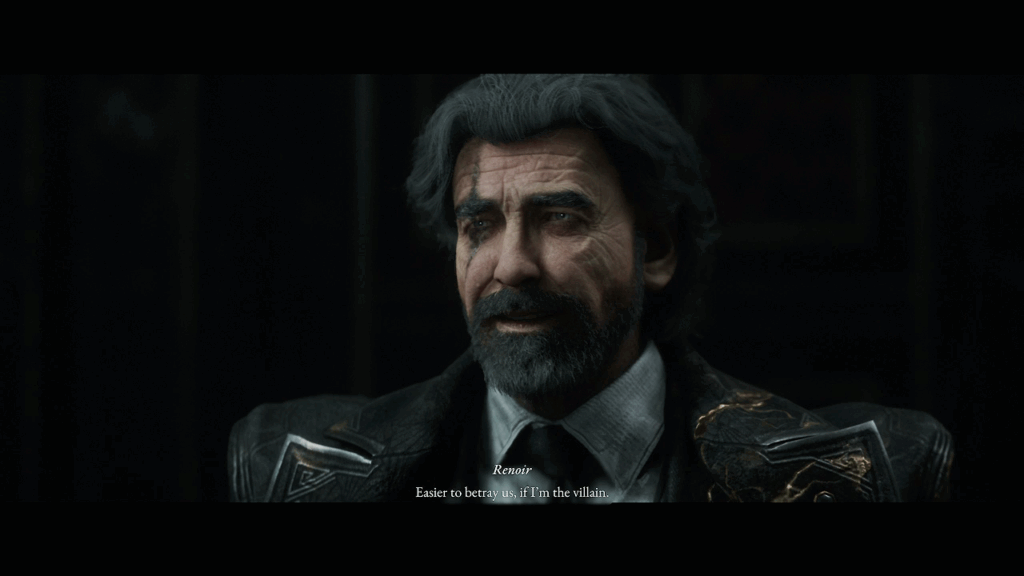

The longer I play, the more Expedition 33’s role in the story is swallowed by the history of this manor, a domestic drama in which they are only significant as its incidental victims. If I haven’t written much about Expedition 33’s individual members, it’s because they feel incidental to the actual conflict that unveils itself. By the final third of the story, their societal-level anguish and grief that totally enthralls me at the start is subsumed by the personal anguish and grief experienced by a single family.

This avoids being disastrous because the characters and details of this domestic drama are strong enough to carry Clair Obscur’s plot once they fully take over. The manor is home to a family with incredible powers whose abilities are only just barely explained. They exist on a tantalizing line between coherent enough to be interesting and vague enough to be unfathomable; their powers are Clair Obscur, both clear and hidden.

The conflicts that arise from this hidden story challenge traditional RPG concepts of right and wrong. The villain’s motivations push against the boundaries of evil and Expedition 33’s efforts to stop them create a new idea of what it means to save the world. As much as I love these elements, the possible endings to this conflict go back to being frustrating. The apparent bad ending spits in my face, my feelings, and my efforts; the apparent good ending spits in Expedition 33’s. It is thankfully not difficult to get both endings. This does little to resolve the ambivalence they leave in me. My catharsis at finishing this story is, once again, both clear and hidden. It’s an unsatisfying conclusion.

Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 is a beautiful, wonderful mess. Its incredible combat systems are the reason to play. They are deep and approachable, challenging and fair, fun to break but not presenting themselves as already fractured. The level design disappoints. Areas are difficult to navigate because environments frequently look the same, they are filled with lazy shortcuts to keep the party on the intended path, and collectively do not fulfill the intricacy they first present. Its plot is its most challenging element. I am fascinated by it from start to finish despite it often leaving me confused by its choices. The story it tells at the start is not the one it tells by the end and if I make an effort to reconnect those two points at the climax, the resulting ending seems to mock me for it. I will spend a long time thinking about how Clair Obscur has treated me.