Twilight Monk is a nonlinear platformer set in a dark fantasy world inspired by East Asian mythology. The story begins on Crescent Isle, the home of the Moonken Monks and a haven where nearby villagers seek refuge when their homes are destroyed by rampaging monsters. I meet its player character, Raziel Tenza, when he has already completed many adventures and become a jaded legend in his own time. He is the chosen of the ancient Moonken Monks and bearer of their sacred artifact, the Phantom Pillar, which he wields as a massive bludgeon in combat. Crescent Isle’s peace is sundered when the Darksprite Nox betrays the Moonken Monks, attacking their Master and revealing a plan to reunite the Three Rings of the Triskelion. If Nox can bring them all to an ancient temple, he will unleash a creature known as The World Eater. It’s up to Raz to beat Nox to the Rings and save the world from devastation.

The strictures of the nonlinear platformer are by now familiar, even dogmatic, in the indie videogame zeitgeist. Twilight Monk does not deviate too far from the expected. Raz’s ability to search the lands beyond Crescent Island for the Three Rings of the Triskelion is limited by the platforming abilities he has discovered around the world. At the beginning of his adventure, plain and unadorned, Raz’s progress is regularly impeded by walls too high and gaps too wide for him to jump over. He discovers his first platforming powerup, the quintessential double jump, and his ability to explore is expanded. By the end of his adventure he has added most of the usual skills to his platforming moveset: Air dashing, sliding, wall jumping, bashing, and the abilities to swing from targets and breathe underwater.

A wrinkle to these nonlinear platforming fundamentals comes from Raz’s Phantom Pillar. He may plant it temporarily on the ground to create a new platform. The additional height it provides is small, but is often the last little boost he needs to reach a target just out of reach from his regular jumps. The Phantom Pillar’s bulk is also useful for weighing down certain buttons that activate doors and elevators. Raz may leave it lying on the button so he may explore beyond a barrier, then summon it back to him in an instant from any distance. While these extra uses prove pivotal at a few key locations around Twilight Monk’s world, the Phantom Pillar ultimately feels underutilized as a platforming tool. I would like to see far more situations where Raz is forced to leave his primary weapon behind.

The real surprise Twilight Monk brings to familiar nonlinear platforming occurs when Raz leaves Crescent Isle for the first time. Instead of entering another side-scrolling platforming environment that branches to one or more other areas, Raz enters an overworld map area called the Speria Plains. This small region is viewed from a top-down perspective where I may steer the player character in any direction. By exploring the Plains, Raz discovers the entrances to other locations. Entering any one of them returns to the familiar side-scrolling perspective where Raz may find the upgrades and keys that let him access more of the world.

I am normally critical of nonlinear platformers that divide their environments with a hub world or a similar connective contrivance. Nonlinear platformers are at their best when they take place in a single, cohesive space. It’s what makes it exciting when the player character defeats a boss or breaks down a wall and discovers a shortcut back to an area they’ve seen before, newly empowered to overcome obstacles that previously impeded them. Forcing them to travel between regions using a vehicle or map screen stifles exploration and discovery. In the best nonlinear platformers, areas do not end, they loop endlessly like ocean tides, brushing against their neighbors in a vast global system.

Twilight Monk does not totally avoid this weakness of hub-based nonlinear platformers. Though each of its areas feels small and self-contained, they are replete with many obstacles Raz will be unable to overcome when he first encounters them, making return visits to previous areas highly rewarding with new collectables and upgrades. The world map itself is also filled with secrets. By wandering away from the main path, Raz discovers hidden coves filled with treasure the main quest will never send him to or a talking tree hiding a blacksmith beneath its root who trades his creations for blue diamonds that drop from rare spiders. The hub world may interfere with the cohesiveness of the platforming spaces, but it is still an interesting space hiding useful discoveries rather than a glorified fast travel menu.

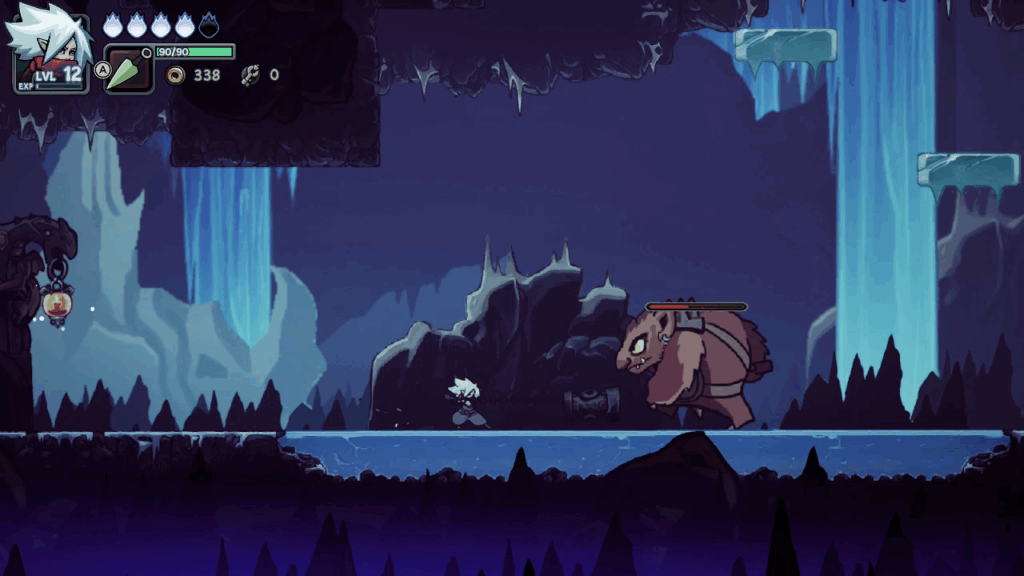

Twilight Monk’s combat is much more typical for a nonlinear platformer. Some monsters are large and try to overpower Raz with slow, powerful attacks. Others match him in size and defensively duel him, lowering their shields only to attack with rapid strikes. Smaller enemies fly and attack with projectiles, dangle down on delicate webs to block Raz’s path, or mindlessly crawl along walls and ceilings. Almost every area introduces some new kind of enemy with a new attacking style to keep things fresh.

Raz’s main tool for dealing with these monsters is the Phantom Pillar. This massive artifact is nearly as wide and tall as Raz but does not slow him down as he carries it slung over a shoulder. It is attached to his arm by a chain he uses to fling it forward and pull it back like a massive yo-yo, crushing enemies beneath its massive weight. When a puzzle or obstacle causes Raz to drop the Pillar, he defends himself with punches and kicks. He is obviously a trained fighter, but the range and power of these attacks are much less than those delivered by the Phantom Pillar. It feels like a depowered fighting state, not an alternate one. Curiously, there is not a single moment across Twilight Monk’s campaign where Raz is forced to drop the Pillar and fight bare-handed. It feels like a missed opportunity.

Variety is added to the combat by Raz’s Mystic Arts. These smaller weapons made from jade are more situational than the Phantom Pillar’s brute force philosophy. Raz’s first Mystic Art are tiny Daggers whose low damage are made up for by their range and the sheer number Raz can throw in a short time. Other Mystic Arts like axes, chakrams, and hammers also provide ranged options but have distinct attack speeds and arcs. Each of them is more or less useful in different situations. Raz can switch between Mystic Arts with a ring menu accessed by holding down a button, making it quick and easy to switch between them as needed.

All of the Mystic Arts are powered by Ember, a green energy meter beneath Raz’s Spirit. He begins with a measly 60 Ember, barely enough to cast most of the Mystic Arts two or three times. Using Mystic Arts regularly still isn’t a problem. Lanterns appear in nearly every room that replenish his supply. The meter is intended as a limiter on how many Mystic Arts he may use in a single encounter, not a damper on how they may be used overall. This being a nonlinear platformer, the Ember meter may be expanded by searching for green crystals hidden around Speria. By the time Raz faces the final boss, provided I make enough effort to explore, he has enough Ember to throw dozens of Daggers.

My ability to customize how Raz performs in combat is provided by Summons and Talismans. Summons are the most straightforward. Raz may choose one of the total four. Each calls a flying companion with a unique ability, like a ball of fire that protects Raz from weak enemies who rely on collision damage—and perhaps unintentionally also reveals breakable walls—and a haunted sword that attacks with erratic, flying stabs at random monsters.

Talismans add the most flexibility. Each enhances one of Raz’s abilities, from adding new behavior to Mystic Arts, to widening the invincibility window when Raz gets hit, to adding a slow regenerative effect to the Ember meter. The most interesting Talismans alter the Phantom Pillar. The more straightforward option increases the length of the chain attaching the Pillar to Raz’s wrist, giving his basic attacks greater range. The more unorthodox allows Raz to kick the pillar after it has been dropped on the ground, turning it into a missile even more powerful than standard swing attacks. A second Talisman further lets him kick the pillar repeatedly. The two options create an interesting strategic contrast, though there isn’t a real choice; there’s nothing stopping Raz from equipping both Talisman sets except the limited number of available slots.

These combat and customization systems are deployed across a campaign with a pronounced difficulty curve. Early in Raz’s quest, the limited number of hits he can take to his Spirit meter makes him feel especially frail. The way damage is calculated adds to this sensation. Each point of Raz’s Spirit is divided into two fragments. The lowest amount of damage a monster can deal is one fragment, or fully one-sixth of Raz’s total. This means that setting out, the lowliest Cave Bat and Skeleton Shuffler are equally as dangerous as the bosses which are nominally Raz’s greatest opponents, and probably greater because of their increased numbers.

Raz’s fragility is especially pronounced early on because of how Twilight Monk tracks progress. Whenever Raz dies, the most recent save automatically loads, overwriting any items obtained, doors opened, and levels up earned after that save. The risk of losing progress incentivizes frequent backtracks to known save points whenever Raz accomplishes something of any importance, especially early on when three or four hits is enough to put his Spirit in a critical state. He may purchase potions which will revive him once, but they are expensive and the Zinny that drops from enemies and destructible objects is needed for other powerups and multiple plot-critical keys.

This situation inverts itself by the end of Raz’s quest. After thorough exploration of every region, his Spirit meter grows more than four times in length. Monsters also begin to drop far more Zinny and there is less that needs to be purchased from shops, making it more affordable to keep a reviving Potion in Raz’s pockets at all times. Even with monster damage scaling up in later areas, these significant buffers help Raz feel more resilient when he approaches the World Eater’s Temple than when he first leaves Crescent Isle. My impulse to save after every minor milestone is much reduced by Twilight Monk’s latter hours.

All of these features come together to create a competent and at times unusual nonlinear platforming adventure that does a good job holding my interest across a twelve-plus hour adventure. This is fortunate, because relying on the plot and characters won’t do the job.

Twilight Monk’s plot isn’t interesting or original. A quest to gather multiple macguffins before the bad guy with the world at stake is a stock videogame premise. The “twist” that Raz is being manipulated to collect the Three Rings of the Triskelion and deliver them to Nox is obvious. These plot shortcomings don’t have to be detrimental if the dialog is well written and clever. It could also be inconsequential enough that I am able to ignore it, freeing me to focus more on mechanics and level design.

Twilight Monk manages neither of these possibilities. Raz’s dialog is mostly bland and straightforward, though when he gets heated he devolves into a preteen boy’s idea of what sounds cool and intimidating. Other characters have ridiculous accents and affectations, like the Moonken Monk Master Klu who speaks like a stereotypical surfer. I understand the theory behind the joke; I expect him to talk like Mr. Miyagi, he talks like a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle. In execution it’s more weird than funny, too inexplicable to elicit a laugh.

Raz encounters these random caricatures across Speria’s multiple towns. Many non-player characters have interesting designs, particularly those who occupy the central hub in Crescent Island. The problem is they are far too talkative, often requiring Raz to speak with an individual multiple times before they begin repeating themselves. I stop pursuing every piece of dialog after a few hours; NPCs have too much to say and too little of it is useful or interesting. The script also likes to CAPITALIZE WORDS for emphasis. It happens so often it crosses from emphatic to idiosyncratic. Twilight Monk’s script as a whole agonizes for a pass from a strident copyeditor.

It is difficult for me to spend any time with Twilight Monk and not be reminded of another videogame: Zelda II: The Adventure of Link. This is most visible on the world map, where shadowy figures appear at random and pursue Raz. When they touch him, he is transported to a side-scrolling battlefield where he must fight off a small monster group before exiting the battlefield from its left or right side, returning him to the world map. This awkward combination of platforming and RPG concepts is pulled straight from Zelda II.

There are many other comparisons to make. Raz finds bags of experience points inside chests, though his experience level increases the damage he deals and none of his other attributes. One area is a labyrinth of short tunnels that connect small valleys between impassable mountains. A dungeon in the desert has a cavernous opening at the surface guarded by a single statue, with a shaft at the far-right of the screen leading into the dungeon proper (attacking the statue does not produce a healing item—I checked). All these features are taken from Zelda’s most divisive legend.

None of these observations are to suggest that Twilight Monk is an unauthorized remake or trite fangame of Zelda II: The Adventure of Link. In execution it is quite a different product, playing more like the voguish indie nonlinear platformers of the past decade than Nintendo’s awkward action/adventure-RPG hybrid. These elements are still here, suggesting its developers are fans and it had at least some influence on Twilight Monk’s overall design.

Twilight Monk is a good nonlinear platformer, made with care and skill, if not groundbreaking ambition. I have to give it particular credit for implementing an interesting hub world into a nonlinear platformer, a feature I usually disdain because it is rarely done to the videogame’s benefit. Exploring this world, disconnected though it may be, to find character upgrades for Raz is engrossing and rewarding. Combat is straightforward for the genre, though Talismans provide some tools to make it more interesting if I’m willing to embrace Raz’s more unorthodox strategies. The script is its main weak point. Its story is obvious and its twist moreso. NPCs are too-talkative, Raz’s dialog meanders between uninspiring and pathetic, and the jokes are too weird to be funny. Twilight Monk is fortunate that story and characterization can get away with being secondary in a nonlinear platformer. In a comfort food genre like this, this is a filling and satisfying meal.