A PR representative provided Play Critically with a review code for this videogame.

Wizordum is a high fantasy-themed retro first-person shooter that deliberately invokes the most significant foundational entries in the genre, creating a distinctly lo-fi experience with horizontal level design and a grueling pace. It is set in Terrabruma, a kingdom besieged by an army of Chaos. Terrabruma’s call for help is answered by the magical stronghold Wizordum, who dispatch their most powerful spellcasters to repel the army. None have returned. I play as one of Wizordum’s last magical soldiers who, like those sent before, is deployed to defeat the Chaos army. Across twenty-one levels in three episodes, this final spellcaster becomes a one-person army who is all that stands between Terrabruma and annihilation.

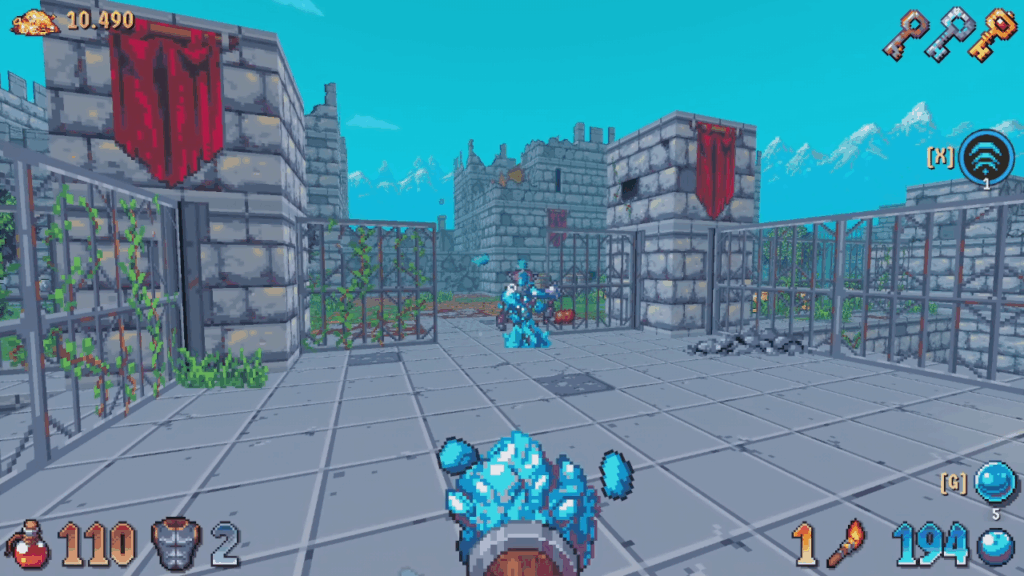

Wizordum’s greatest feature that makes it distinct in the crowded indie marketplace is its visual aesthetics. Every space in Terrabruma has a rigidly cubist shape. Every roof is the same height, every pit is the same depth, every corner has the same hard right angle, and every wall, no matter how long, perfectly divides down to the same least common denominator. Wandering the besieged kingdom’s twisting spaces feels like exploring a labyrinth built from graph paper and simple wooden blocks on an ambitious dungeon master’s tabletop.

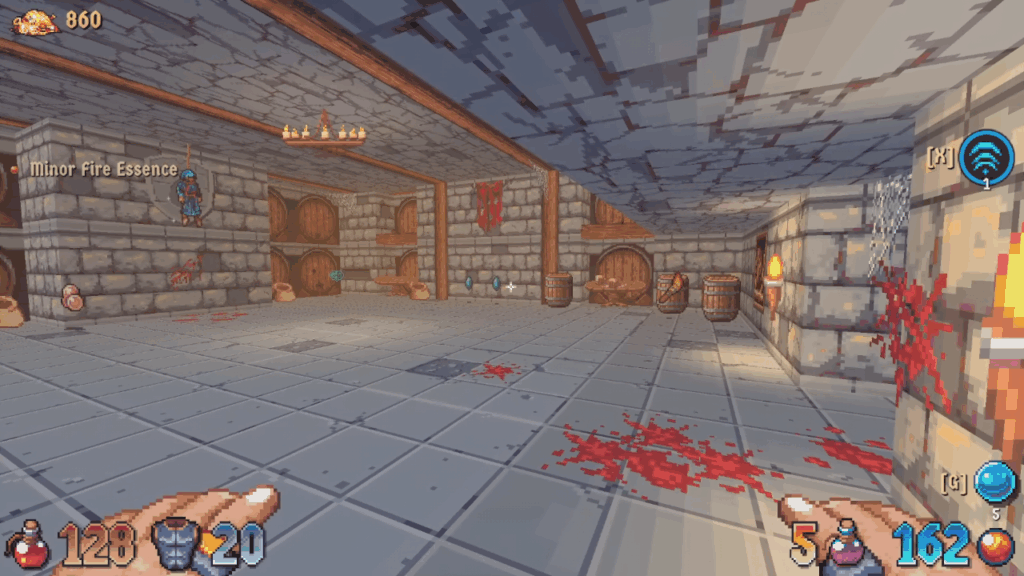

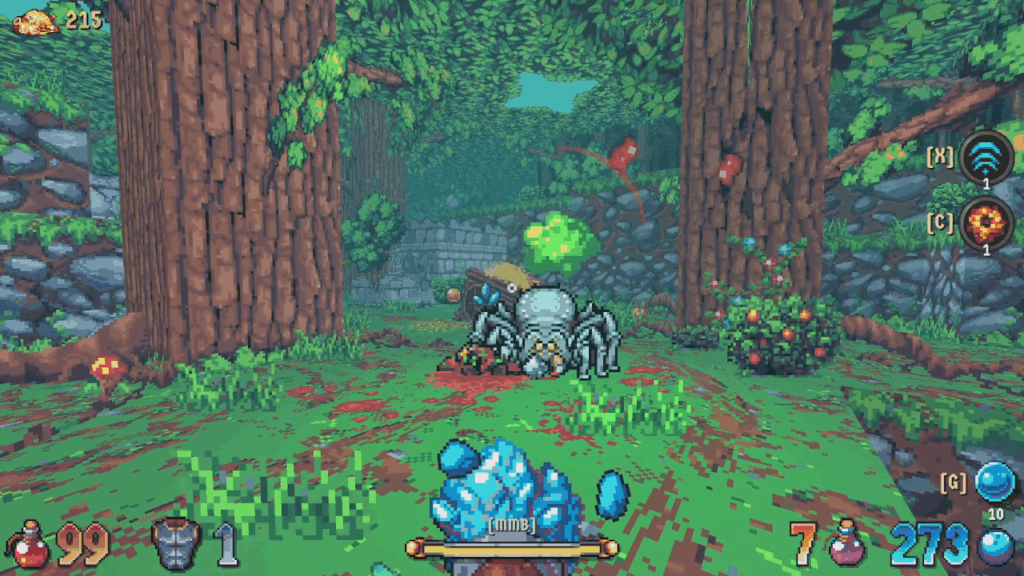

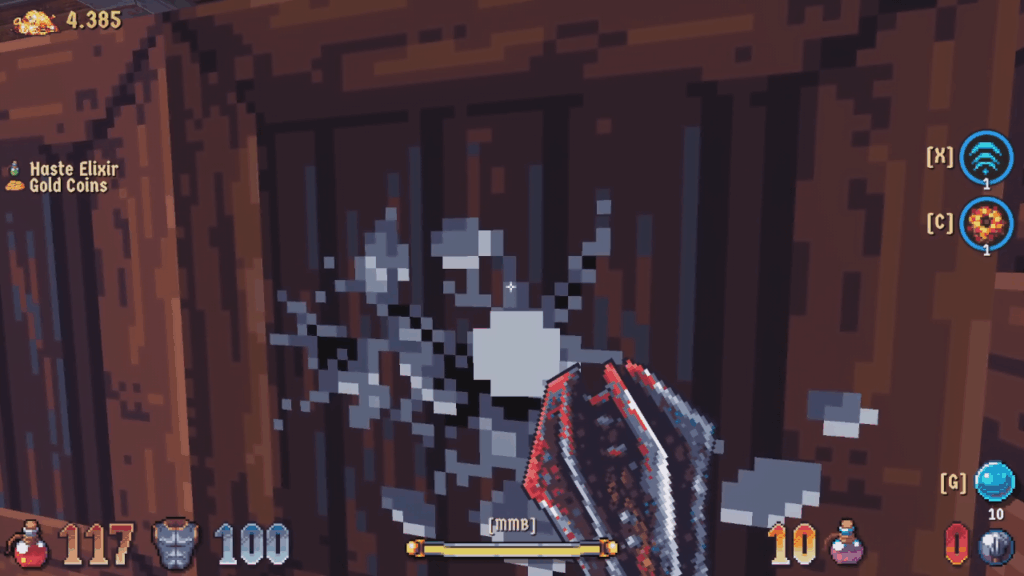

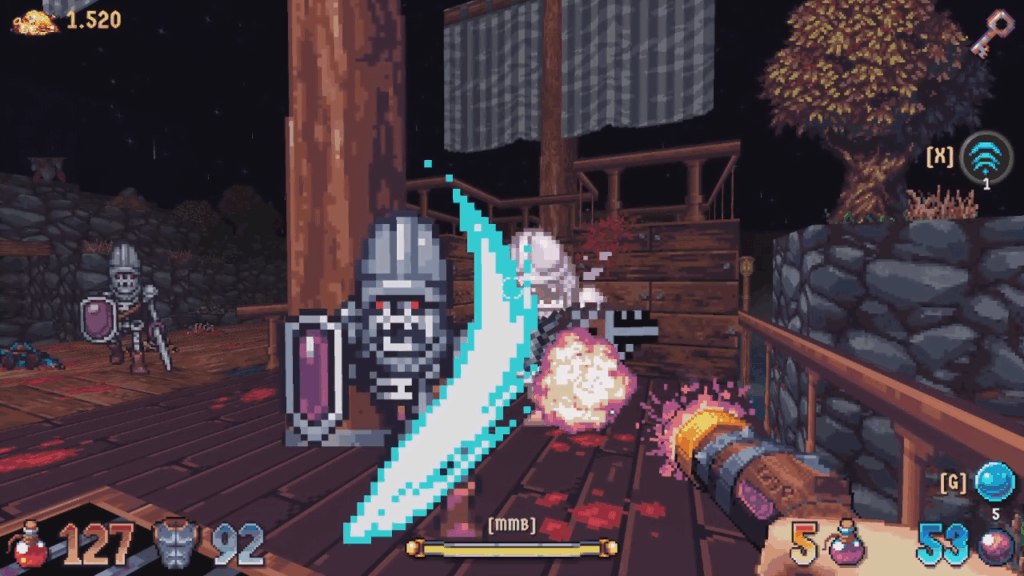

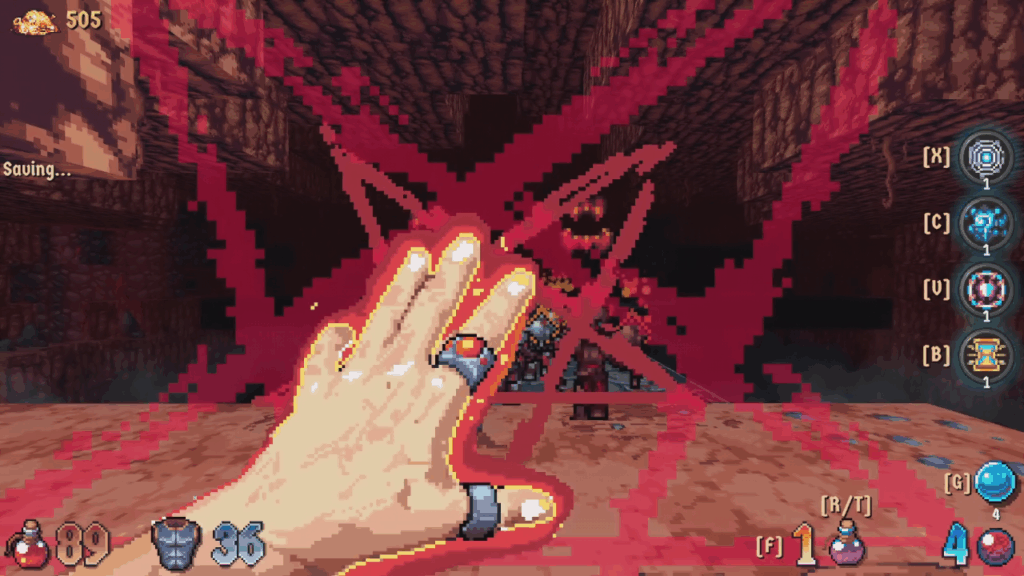

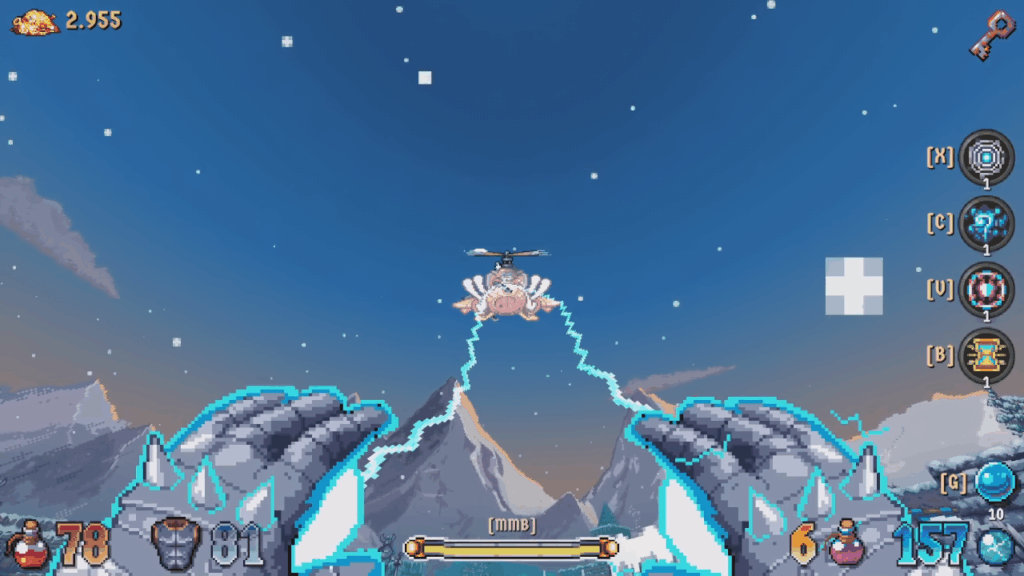

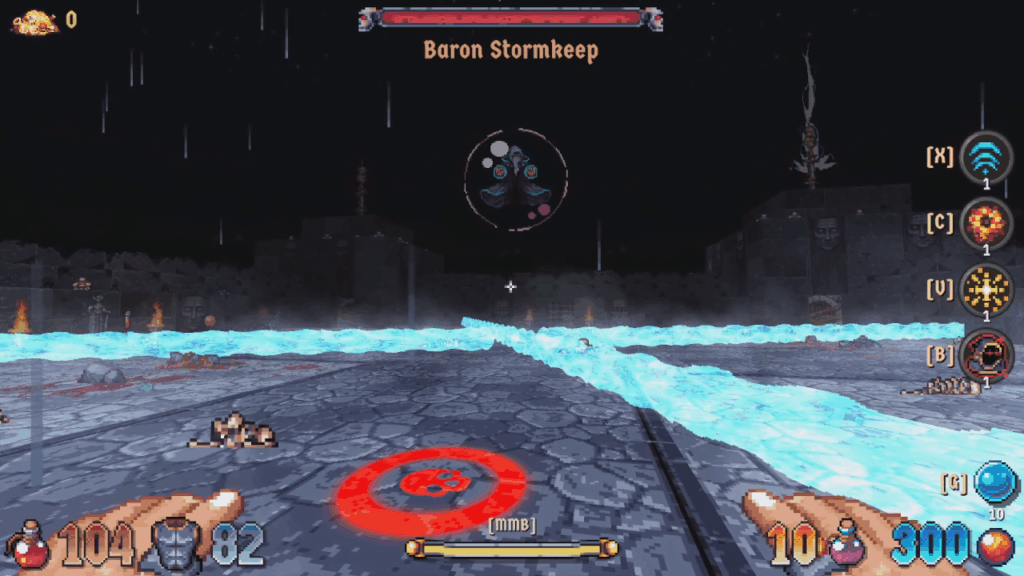

All of this uniformity could look incredibly bland if it’s not matched with strong visual design. Wizordum is up to this challenge. Every surface in Terrabruma is decorated with the accoutrement of a classic fantasy setting. These textures are not created with density or subtlety. Every pixel is big and obvious and beautiful and demands to be seen, whether it depicts a fragment of worn wood, weathered stone, or trampled grass. All these features are created with a bright color palette that defies the gore the player character witnesses and the bloodshed they mete out on the evil Chaos army. Existing in Terrabruma is like being transported back thirty years in first-person videogame history when the cartoonish and the grisly intermingled freely.

The visuals’ real trick is that they contain no true 3D objects. Decorative features like trees, wells, and overturned carts spin in place while the player character circles them. The goblins, zombies, and evil sorcerers that make up the Chaos army are similarly limited; when they are magically frozen or lying in an eviscerated pile on the ground, they remain facing the player character’s perspective as though they are trying to win a deathly staring contest. Even the weapons the player character wields and the hands which support them on the screen’s periphery are obviously flat, though drawn with greater attention to shadow and texture than the environments.

When all of these visual elements come together, it creates a hypnotizing lo-fi effect. It is the first thing I will associate with Wizordum when I look back on it in the future.

Another strength is the level design. In even the best first-person shooters, their most memorable levels are a result of set pieces within them and not the level as a whole. DOOM II’s “The Crusher” is an iconic level, though outside of its titular set piece, its other rooms are functional as a videogame environment and not as a practical one. Wizordum’s spaces are more in line with BioShock’s Rapture, encompassing a believably liveable environment that still operates as a fun place for videogame shooting. Across all of its twenty levels, I can tell exactly what the space the player character occupies is supposed to be and the function it serves in Terrabruma.

Wizordum’s earliest levels feel like the most classic fantasy setting. The city of Grimbrook is under siege by a goblin army and each of its features serve as a unique level where the player character may battle. A castle ruin on Grimbrook’s outskirts leads into streets that zigzag around a canal, then massive sewers beneath the city center, and then the huge commercial dock that brings trade and produce to the city. Later levels enter more mysterious and conventionally evil territory, like an ominous pyramid in a creepy swamp and a demonic crypt set high on a frigid mountaintop. No level recycles an idea. It takes until Chapter 3 for Wizordum to revisit a populated city and the contexts could not be more different. Chapter 1’s City of Ember is a city set aflame by an invading goblin army. Chapter 3’s Hollow Ridge is a forsaken mountain hamlet buried in snow. Even when an idea is similar, in execution it’s still completely different.

Each level is densely designed, filled with winding corridors and innumerable sequestered corners where monsters lie in ambush and pickups are hidden. Some levels have additional environmental flourishes that add an extra level of reality. The player character must trudge through knee-deep pools that fill moats, sewers, and swamps. Some spaces are so dark, the player character can only see a few inches in front of them unless they use a torch item. Torches last for only a few minutes and are limited in quantity. If the player character uses all their torches, they have no choice but to brave the darkness and the monsters lurking within it.

A particular throwback to classic first-person shooters are hidden rooms and spaces filled with treasures and opportunities to pick up powerful weapons. Some secret rooms are found the old-fashioned way: When a particular wall is activated, it slides backwards, revealing the room. This wall is always adorned with a painting or other decoration that makes it stand out in the environment. Moving forward a few years in first-person shooting design, other secrets are found behind walls that can be broken down with the player character’s weapons. Still other secret rooms only open when special locks are shot with a weapon. These locks are often hidden in high or low places, adding a needed sense of vertical discovery to spaces. At other times, these locks are disguised as innocuous parts of the environment distinguishable only by the “Use” command that appears when the player character stands in front of them. Secret rooms sealed by these locks are the most obnoxious to open. Thankfully, there is no requirement to find any of them.

The weaker design in these levels are the results of the engine that drives them. The player character is locked to a single elevation, making spaces feel flat. Though monsters can perch on elevated platforms to fire arrows or fling fireballs, the player character can never drop down into a pit or climb a set of stairs up to a balcony or rooftop. If they do encounter a sheer drop, an invisible wall keeps their feet safely on the ground. These limitations make Terrabruma’s few spaces that are wide and open still feel winding and claustrophobic. Since these feelings are a benefit in a first-person shooter, it’s not totally a problem that needs to be solved, though the inability to drop from a high place to a low place is limiting to the level design.

In order to reach higher and lower elevations, the player character must interact with a trap door or stair set that is literally painted onto a floor, wall, or ceiling. It’s easy to mistake these as decorative features, sometimes turning progress into a pixel hunt. Interior spaces suffer from a similar problem. Wizordum’s early levels do not support them, so when the player character “enters” a house, they are really traveling to another space on the other side of the map. Doors and stairwells drawn on surfaces function more like teleportals than footpaths, making their use disorienting. Even when a doorway moves the player character up or down in the same room, it still feels like being transported from one flat space to a completely different flat space.

All of these spaces overflow with the Chaos army that overwhelms Terrabruma. Its core is made up of goblin soldiers. Small goblins will try to swarm the player character, distracting them with swings from their tiny weapons to give their magical siblings space to fling fireballs. Many goblin packs are led by hulking captains who can buff their smaller companions, adding a whole new layer of strategy and difficulty. As the player character’s quest takes them away from the besieged Grimbrook, they encounter a greater variety of magical monsters. Spiders skitter between trees and bushes in their forest, stopping only to spit poison globs at the player character while their back is turned. Angry revenants with mushroom heads rise from swampy water and use a long tentacle to pull the player character in close for powerful swings from their fetid claws. Over time, the goblins are replaced by skeleton warriors who may reanimate themselves after they are defeated.

The monsters are key to Wizordum’s biggest weakness: its sound design. Most monsters are strangely silent. They do not growl or roar when they spot the player character and move in to attack. When skeletons reanimate from a pile of bones, the magic bringing them back to life is inaudible. This makes it easy to be ambushed. I often have no idea the player character is in danger until a peculiar swishing sound, like a thin wooden rod being swung through the air, accompanies the sword or axe swings pelting their back. The effects of fireballs are even more unusual, impacting surfaces with a sound like snapping fingers. These sound effects, already doing too little to inform me about what is happening around the player character, are easily drowned out by the suitably bombastic and heroic soundtrack. It’s easy to overlook the sound design aspect of videogame design until I encounter it being done poorly. Wizordum is one of these instances. Little in it sounds right.

To combat the inaudible terrors that occupy Terrabruma, the player character equips themselves with nine magical weapons. Three are the workhorses of the player character’s arsenal, seeing constant use in almost every level. The Fire Rings launch a barrage of fireballs from the player character’s hands. It’s steady, accurate, and powerful, making it the most reliable tool in the player character’s arsenal. The Spellstriker is a small handgun that fires a spread of magical projectiles; despite its unassuming size, it is Wizordum’s equivalent of the reliable shotgun and is useful in the exact same contexts. My favorite of all the weapons is the Frostweaver. This frozen rod rapid-fires tiny icicles that can freeze most monsters in a few hits. Hitting them one more time in this frozen state with any other weapon will kill them instantly. The magical gems that power all three of these weapons are plentiful, ensuring I can use them almost whenever I need to.

The remainder of the arsenal have ominous names like Pyroblast, the Eye of Chaos, and the Grimoire that suggest the player character’s awesome power as a practitioner of magic. Just one shot from Pyroblast can obliterate entire groups of enemies. The Storm Gauntlets and the Faewood Crossbow have more specialized uses but feel no less powerful when wielded against the right enemies. The ammunition for these weapons is scarce, forcing the conservation of their awesome power for situations when the player character really needs them.

Between levels, the player character visits the Sorcerer’s Shop where they may purchase upgrades using the gold they pick up in levels. The most notable upgrades are new secondary fire options for every weapon. The Fire Rings’ alternate mode spits a flame torrent from the player character’s hands. The Frostweaver’s makes every frozen enemy shatter, dealing damage to any other enemies standing near them. These alternate firing modes are interesting but also burn through phenomenal amounts of limited ammunition. They’re more cool to look at once than practical to use regularly.

The remaining weapon is the player character’s starting one. It requires no ammunition to fire, making it handy in the search for secret rooms behind breakable walls and smashing open containers that contain treasure, ammunition, and items. There are two of these default weapons and which one the player character wields is determined by the character class I choose when beginning a new campaign.

The two available classes are the Cleric and the Sorceress. The difference between the two is most immediately identifiable by their default weapon. The Cleric is equipped with a mace, Wizordum’s only melee weapon. It is a good choice for smashing open containers and walls. It is a less good choice as an offensive weapon. The player character is fragile regardless of the class I choose, so putting them in melee range of even a single enemy is a tricky and dangerous idea. The Sorceress’s wand is weaker than the mace, which makes breaking open containers with it a tedious process—and Terrabruma has a lot of containers to smash. Its ranged capabilities still creates situations where she can bombard enemies safely from a distance when ammunition reserves for her main weapons are light. The wand is ultimately the more practical choice if I can swallow the extra time needed to collect items from containers.

The other differences between the two classes are philosophical. The Cleric has a larger hit point and armor pool than the Sorceress, while the Sorceress moves slightly faster. Both classes discover three unique spells and a special super attack while exploring Terrabruma. The Cleric’s abilities focus more on defense and recovery, while the Sorceress’ focus on movement and damaging enemies. These spells may be cast freely and their cooldowns recover quickly as the player character defeats enemies, encouraging their liberal use when fighting the Chaos army.

Where I struggle with Wizordum is I often forget to use these spells at all. It has too many tools to keep track of and the class’ unique spells often get lost in the shuffle. In addition to the nine weapons and four class-specific abilities, the player character can also pick up almost a dozen different items which provide temporary effects when used.

The effects of these items are numerous and varied. A Cloak of Invisibility lets the player character slip by monster groups, potentially setting them up to attack from a more advantageous position. Elixirs increase their movement speed or defense. A poison vial leaves a cloud of damaging smoke on the ground. There are even single-use scrolls that give each class limited access to their counterpart’s unique spells. It’s all too much to keep track of on top of an interface that makes it almost impossible to select these items in the pressure of battle. The player character picks up dozens of items over the course of their adventure in Terrabruma. The only ones I direct them to use are healing potions and torches.

At the time I write this review, Wizordum is approaching the end of its Early Access period and is nearly feature-complete. The first two episodes comprising the first fourteen levels are all in a solid state and if they were the entire videogame, Wizordum would get my firm recommendation. The third episode and final seven levels are being actively refined as I play them and they are where I experience the most difficulty enjoying my playtime.

The third episode has unique elements and ambitious design that suggest a videogame approaching its climax. The setting moves to a freezing mountaintop whose interior hides macabre and demonic secrets. There are new enemy types to fight, including goblins piloting wooden flying machines, boulder-hurling golems, and shrieking vampire nobles. There are interesting set pieces, like an army of monsters obscured in a smoke-filled hallway suspended above a fiery trench and a bizarre snake contraption made of moving blocks that crushes anything that wanders into its lumbering path.

Some of the third episode’s new elements even improve upon the limitations I encounter in the early levels. Some areas contain actual, functional doors—though “wall portals” still abound. Other areas feature elevators that carry the player character between floors and a minecart that careens up and down ramps. I can still feel the limitations of Wizordum’s creation tools in these features. The player character is locked in place while the elevator and minecart follow their paths, making them more like cutscenes than interactive parts of a level. When I try to retrace the player character’s path back along the minecart track, its slopes are blocked off by invisible walls. They are illusions, but an important step in advancing Wizordum into fully functional 3D spaces.

My enjoyment of these new, more ambitious levels is impeded by technical errors. After defeating the second boss, Wizordum transitions to a black screen I can only escape by force-quitting the application. Resuming a saved game traps me on a loading screen if it was made while the player character is in certain, arbitrary sections of a few levels. This error is especially problematic given that Wizordum is heavily built around quicksaves and quickloads like the classic first-person shooters it models itself after. Because of these errors, I was only able to complete the remaining episodes by using developer controls on the console to access a level select screen. This method resets all the player character’s resources to minimum defaults at each level’s beginning, making them seem much harder than they actually are.

I presume and hope these problems will be fixed for Wizordum’s 1.0 release that will coincide with the publishing of this review, but I cannot know. I will add a quick addendum reporting whether these problems were addressed at that time.

(Quick addendum: Episode two now properly transitions into episode three instead of a black screen. My old saves still get stuck on a loading screen, but that’s probably because they’re old saves and new saves will probably work. The final boss continues to fight even after its hit point meter is drained. I do not know if this intended or not. It does not feel like what is supposed to happen).

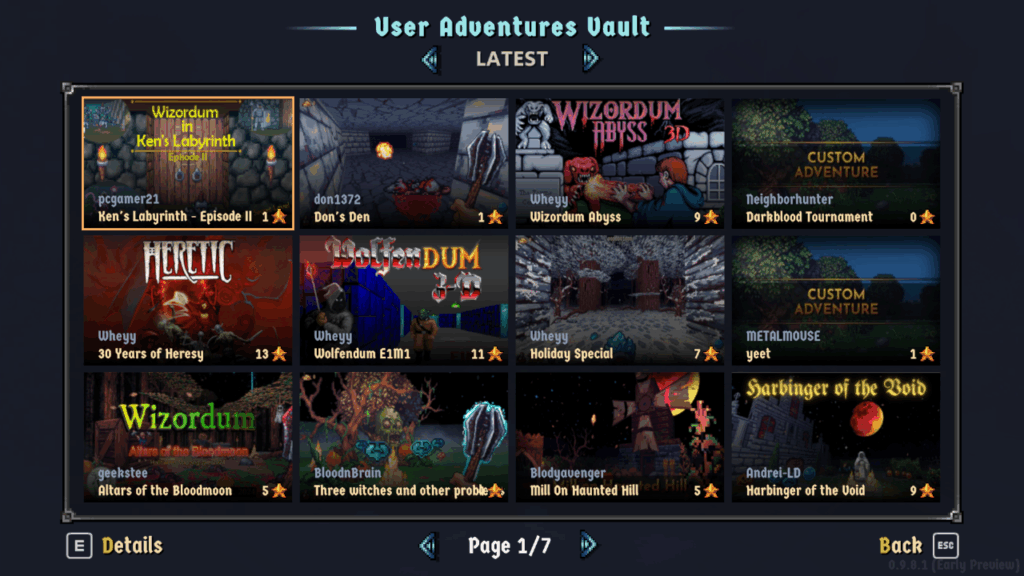

Even if the third episode remains in a perpetual state of black voids and neverending loading screens, it doesn’t have to be the end of my time playing Wizordum. It includes a level editor and integration with the mod.io platform to distribute them to other players. I tried to make a rudimentary level but found the editor’s interface confounding and inscrutable. That hasn’t stopped other players from making and sharing their own creations. The modding and custom level communities for first-person shooters like DOOM are largely responsible for their longevity, so the inclusion here in Wizordum makes perfect sense. Strong community support could carry it far into the future with regular and free new levels. At the least, there’s a bit more for players to check out now than just the default campaign.

Wizordum is a wonderful throwback to classic first-person shooters whose technical limitations only enhance its retro feel. Its level design is a particular highlight, creating settings with a real sense of place and purpose and overcoming a pervading sense of flatness to create environments that are engaging and fun to explore and fight in. The player character’s magical arsenal is an excellent collection of fun weapons. None stand out as obviously overpowered and their many unique abilities make it fun to switch regularly between them. Wizordum’s greatest flaw is its sound design, particularly for its monsters. It fails to communicate their power, where they are in relation to the player character, or what abilities they are using. Despite this notable detriment, I still had a great time playing Wizordum. If the many technical flaws marring its third episode are fixed in time for its 1.0 release, it is an easy recommendation for any player who charts their first-person shooting fandom back to the likes of DOOM, Hexen, and Duke Nukem 3D.