Rift of the NecroDancer is the third entry in an indie music videogame series that has consistently confounded expectations. The original Crypt of the NecroDancer appears to be a typical turn-based dungeon crawler, akin to Rogue or Mystery Dungeon, but with the unexpected twist that the player character must move through the grid-based dungeons with the relentless beat of a fast-paced electronic soundtrack. Its sequel, Cadence of Hyrule, transports that concept to Nintendo’s kingdom of Hyrule, blending the first installment’s rhythm- and grid-based movement with the open-ended world and puzzle-based dungeons of classic Zelda videogames. Rift of the NecroDancer is the most recent release and makes the interesting choice to reinvent the world and characters into an apparently conventional and familiar rhythm/music videogame experience. It would not appear out of place alongside Dance Dance Revolution, Guitar Hero, Amplitude, and similar titles of the late-2000s music videogame trend. Despite this seeming capitulation to the trite and safe, the concept is given a NecroDancer twist.

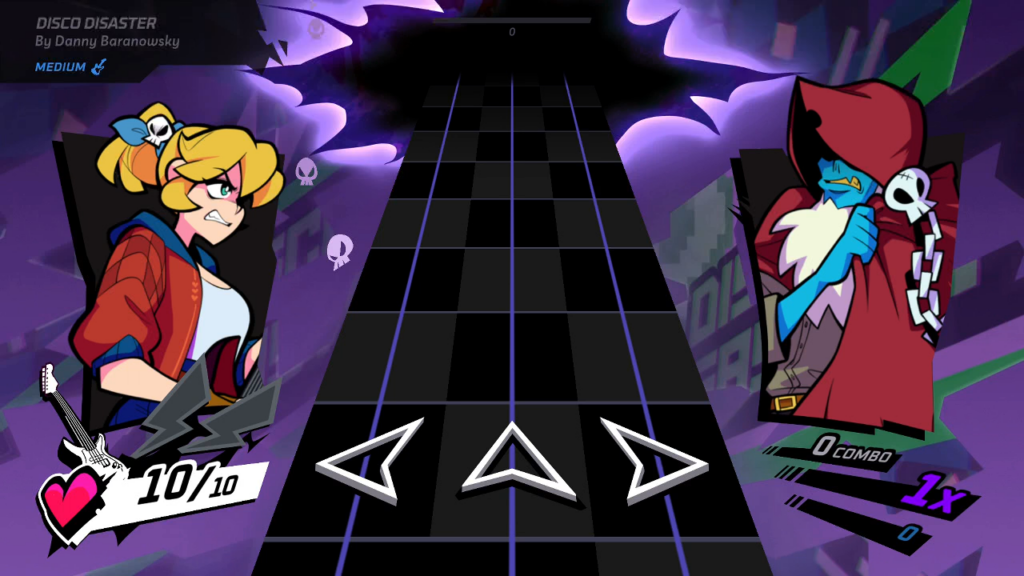

When I play the first song in Rift of the NecroDancer, it strikes me with déjà vu. A black column dominates the screen’s center, stretching from an ominous rift in the background to the screen’s bottom. Gems cascade down this column as the song plays, zig-zagging between three rows in a pattern that roughly follows the rhythm and tune of the music. Each row is assigned to a button on the gamepad. My job is to press the appropriate buttons when one or more gems reaches their row’s bottom. When I perform well, it approximates playing the song using a videogame controller as my electronic instrument.

From a surface level, playing along with these songs seems easy. Each row is assigned to a logical button on a standard controller. I can use either the D-Pad or the face buttons, with the left, top, and right buttons activating the left, center, and right rows, and the bottom button activating all three at once. These three options add up to a possibility of seven total button combinations, a miniscule number by the standards of the genre’s foundational predecessors.

My initial impulse is to take advantage of this simple control scheme and play every note using just the face buttons. I get away with it for the first half of the tracklist. This plan becomes less effective as faster and more difficult songs send so many notes at a rapid tempo down the column that the only way to hit them all is to use both of my hands on both button sets. This minimizes time wasted moving my thumb between buttons and lets me alternate between both sides of the controller when multiple gems of the same row must be pressed in quick succession. The challenge grows as I adjust to this new strategy, evolving from the difficulty of hitting every gem that appears in the field to also remembering where my fingers are on the controller while I try to keep up with multiple notes per beat. Rift of the NecroDancer’s note charts seem simple when compared to the likes of Guitar Hero or Dance Dance Revolution. This is a deception as devious as any of the NecroDancer’s plots.

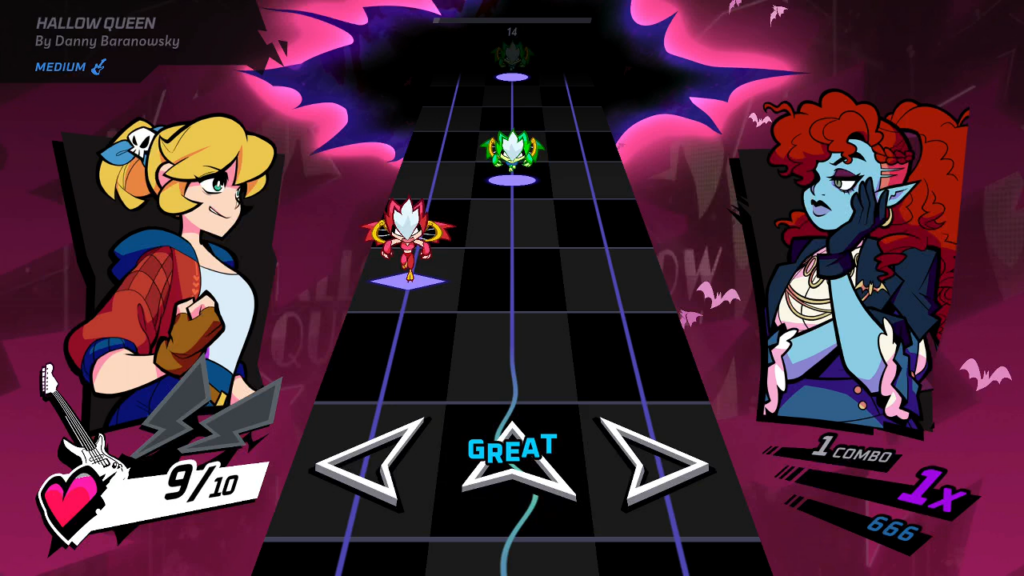

The twist to these familiar rhythm and music mechanics, and the element that makes this a true NecroDancer videogame, is the symbols that represent button presses are not gems at all. Each is replaced by one of the monsters that danced around the NecroDancer’s Crypt, now moving up, down, and sideways along the column with the beat of the music. Rift’s challenge comes not just from keeping up with the music’s tempo but also interpreting how these monsters’ movements translate into the gem notations they overwrite.

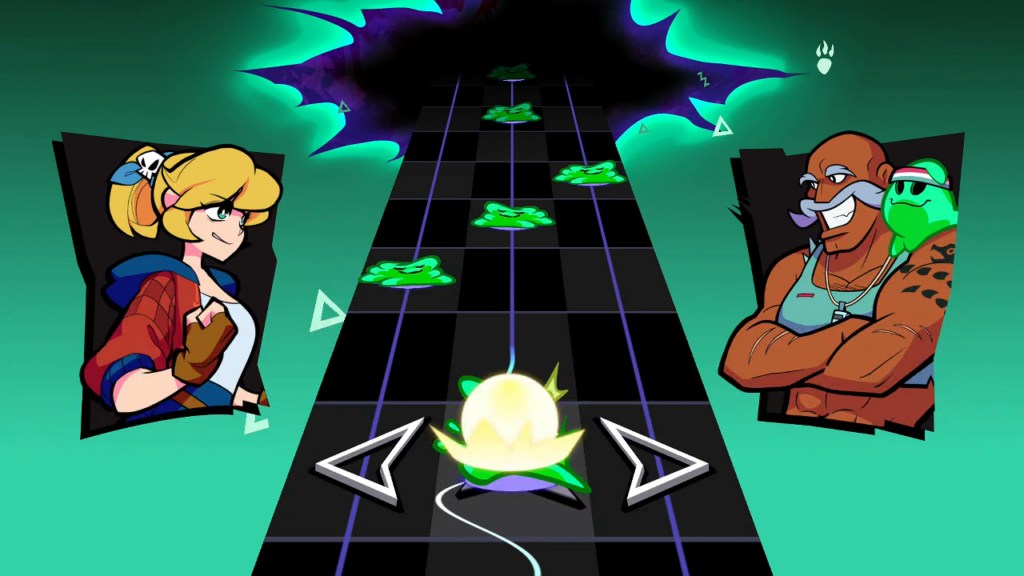

Nearly all the monsters from Crypt of the NecroDancer reappear in Rift and each moves across the column in a unique pattern. Slimes are the first monsters introduced and, in the easiest songs, the most numerous. They move in a straight line directly down the column, bobbing in time with the beat. Monsters are further specialized by their color. Green Slimes are defeated with a single hit. Blue and Yellow Slimes take two and three hits respectively before they disappear from the column, sliding back when they are struck then moving forward again on the next beat. These rules mean Green Slimes are one-to-one translations of the gems obscured beneath them, Blue Slimes are the equivalent of two Green Slimes in a row, and Yellow Slimes are the equivalent of three.

Slimes become less common as songs grow more difficult, disappearing almost entirely by the end of the tracklist, replaced by other monsters with patterns that are much trickier to read. Zombies have similar durability to Slimes, but they hop diagonally between rows on each beat. Bats always take two or three hits to defeat and hop between rows each time they are struck. Skeletons lose their heads when they are hit, rebound back up their row until they collide with another monster, then make their way back down where a final hit finishes them off. For Wyrms, I must hold a button down for the duration of their long bodies, even as other monsters continue to cascade down the remaining two rows.

The trickiest monsters are the Harpies. They move down their row two squares at a time, but only on every other beat. This technically means they are the equivalent of Slimes, though I have difficulty convincing my brain of this. Harpies are made worse by their red variety, which do move on every beat. They are the only monster with a variety that has a different movement ruleset from their fellows. Any song that includes Harpies is much harder than it first appears since their erratic movement makes it difficult to tell when they will reach the screen’s bottom alongside other monsters, who at least have the courtesy of marching in lockstep with their neighbors.

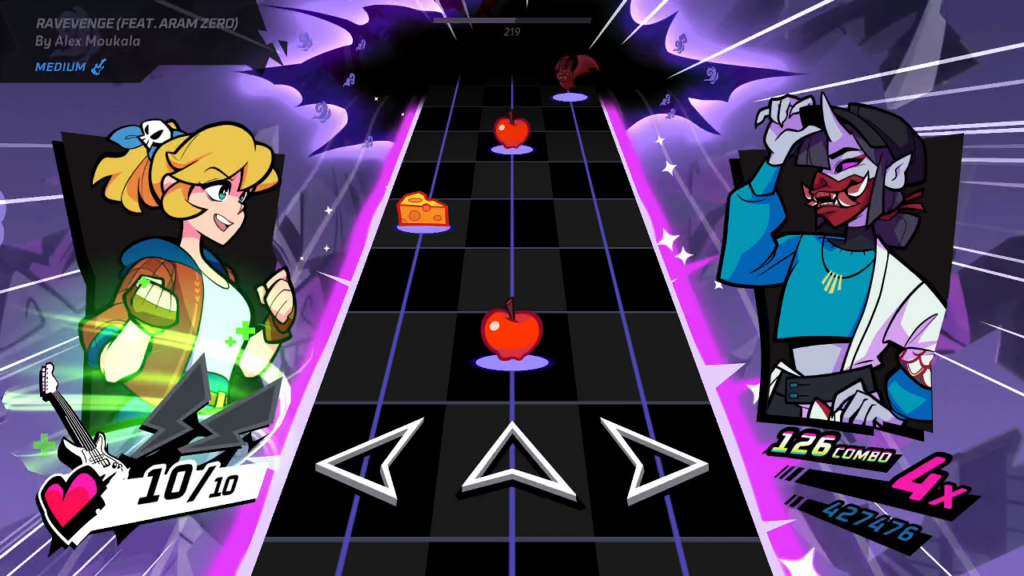

The final twists are the magical effects which occasionally take hold of the column. Shimmering cracks may appear which transport monsters to other rows, perhaps even depositing them directly at the column’s bottom. Molten eruptions set monsters aflame when they pass over, sending them rocketing downwards. Blocks inscribed with question marks obscure monsters who pass over them, forcing me to watch the top of the column to memorize what’s appearing while simultaneously watching the bottom of the column to hit monsters passing across it. With the already tenacious difficulty the dancing monsters add onto traditional rhythm/music design, these magical additions feel like overkill. Thankfully, they are only utilized in a handful of songs.

Another NecroDancer-like element brought to familiar rhythm/music videogame concepts is a health meter. If a monster makes it to the bottom of their row and I fail to press its button on beat, then the player character takes a single hit point of damage. She has ten total, and if her entire stock is drained, the song immediately ends and I must retry it from the beginning.

I may restore any damage the player character takes by hitting the food that occasionally appears in the column alongside the monsters. It’s nice to have this recovery method but it’s a token gesture at best; if I’m doing badly already, I am likely to continue doing badly and miss the food pickups, or immediately squander them in the next section of the song. If I’m doing well, I don’t need them in the first place. The player character also gains temporary invulnerability when I activate her Vibe Power. She earns charges for this mode when I hit every monster in a chain who crackles with electrified energy. The same caveats apply: If I’m doing well, I don’t need the invulnerability, and if I’m doing badly, I am unlikely to earn it. Vibe Mode also wears off quickly. It lasts only a few seconds on the fastest songs, limiting its usefulness as a shield, particularly on the most difficult songs.

These health and damage systems are the weakest aspects of Rift of the NecroDancer’s new approach to typical rhythm/music design. Before the market bottomed out from oversaturation and declining interest from players, later-stage rhythm/music videogames began to embrace letting the player continue all the way to the end of a song no matter how badly they performed. A low score is a much less demoralizing and frustrating punishment for playing badly than an old-fashioned game over screen and a boot back to the song’s beginning, especially since it’s often one particularly tricky part of the song which dooms them. Rift of the NecroDancer is no different in this regard and I wish it had been given as radical a change as the traditional field of cascading gems.

Each song comes with four distinct monster charts rated at four different difficulty levels. When I first begin playing, I let my ego get the best of me and insist on playing on Medium difficulty. I can play any song in Guitar Hero or Rock Band on Expert difficulty; this should be easy. I perform well at first, but some of the later difficulty songs humble me as I have yet to absorb some of the fundamentals. I drop the difficulty down to Easy—which is, as I feared, perhaps too easy—and then loop back around through the songs on Medium difficulty again. This time, I am able to conquer them. There’s a tight ascension from Easy to Medium to Hard difficulties that does a good job acclimating me to Rift’s subtler concepts over time. The songs should be played in ascending order of difficulty starting on their Easy variations and progressing into Medium and Hard, regardless of my unearned self-confidence.

The transition into the highest difficulty is less smooth and it is given the apt title of Impossible. Even the easiest Impossible difficulty songs send a dizzying number of monsters down the column. Getting off the beat or losing the pattern of oncoming monsters for even a moment will decimate the player character’s few hit points in seconds. When a player finishes a song without missing a monster, their high score is marked with a Full Clear badge on the leaderboards. The Impossible difficulty is so furious that, at the time of this writing, there is only one player with a registered Impossible difficulty Full Clear badge, a player who goes by H4u who managed it on the song Glass Cages by Josie Brechner. I salute you for this feat, whoever you are.

Aside from the Impossible difficulty, Rift of the NecroDancer also challenges me with a Remix Mode. The standard songs utilize the same monster patterns every time they are played. Since these monsters are really just overlayed over a series of preset gems, the Remix Mode takes advantage of this to randomize the monsters that replace them. This obliterates the patterns which makes it remotely possible to finish a song through anything other than rote memorization. Remix Mode on Impossible difficulty is Rift of the NecroDancer at its most obnoxiously difficult, the equivalent of playing another rhythm/music videogame wearing a blindfold. If that still isn’t enough for me, I can also activate Aria Mode, which makes anything but a perfectly timed note count as a miss. Many Impossible-difficulty songs still have no registered Aria Mode high scores and maybe never will.

At this early stage in Rift of the NecroDancer’s release, it contains 36 songs total encompassing a variety of genres created by a gaggle of talented electronic composers. Danny Baranowsky appears most often, and with his pedigree from the previous NecroDancer titles, Super Meat Boy, and many other indie videogames, his prominence makes sense. His contributions typically have a blazing tempo with significant drum backing, though the horn-driven Count Funkula and the pseudo-theremin in the spooky Hallow Queen create some welcome variety. Three of his songs from Super Meat Boy are even available as bonus tracks and they are befittingly among the most difficult songs in the tracklist.

The remaining songs offer even more variety from other electronic artists of varying notoriety. Alex Moukala’s dance-infused tracks incorporate unusual sound effects and, in one case, Asian string instruments. Jules Conroy’s tracks contain lots of guitar shredding, as though these songs were misdirected on their way to a Guitar Hero sequel. Sam Webster & Nick Nausbaum’s songs have slower tempos and ethereal tunes with many repeating parts, though they still contain tricky sections which should not be underestimated. There is also a premium downloadable content pack featuring music from the precision platformer Celeste. I expect and hope many more indie videogames will find their soundtracks featured as DLC in the months and years to come. Almost everyone will find at least one song in Rift of the NecroDancer they will enjoy, though I fear the overall tracklist will not change the mind of anyone who does not already enjoy electronic music.

Rift of the NecroDancer does have a plot. I have not mentioned it until now because it is not a significant part of the package. The main menu makes this clear. Its first option is Play, which takes me to a long menu containing all 36 songs I may play in any order I choose. The second option is Daily Challenge, a mode that picks a random song for the community to play in Remix Mode and compete on a daily leaderboard. The third option, finally, is the Story Mode. Its tertiary importance feels deliberate.

Rift of the NecroDancer’s introductory cutscene depicts Cadence, the series’ main heroine, fighting monsters with her shovel inside the NecroDancer’s Crypt. A rift of light envelops her and transports her to a contemporary city where Cadence, her friends, allies, and enemies are transformed into young urban professionals. Her shovel replaced by an electric guitar, the determined heroine sets out to search the city for the source of the rifts.

There are possibilities for an interesting story in this premise. Simple dialog sequences give Cadence a chance to converse with her supporting cast more freely than they could in Crypt of the NecroDancer, giving them more personality and a chance to distinguish themselves through their flaws and aspirations. Some characters are put into especially interesting situations by their transformed new lives. Cadence’s nemesis, the NecroDancer, even turns up as a pathetic fast food fry cook who is too busy trying to survive in a city on a minimum wage job to be up to any evil plots.

This possibility is squandered. After wandering the city for a few chapters following red herrings, Cadence discovers the NecroDancer is lying and he’s responsible for the rifts after all. His boring take-over-the-world plot makes me lament the lost days when he was a hidden schemer who literally stole people’s hearts. He is defeated, Cadence and her friends use a magical artifact to seal the rifts, and the world is saved. The end. The story’s structure seems to follow a checklist of all the pre-existing NecroDancer characters. Once all of them are met, the story rushes to a contrived and disappointing ending following the laziest possible route. It doesn’t even utilize all the available songs.

If the Story mode’s unimportance were not telegraphed by Rift of the NecroDancer’s own main menu, I would be more cross about its shortcomings. More effort is put into the standard Play mode, and that’s where most of my time, effort, and attention is focused.

The Story mode does have one redeeming feature. In between the standard Play mode, Cadence is invited to participate in rhythm-based minigames based on her friends’ new occupations, each incorporating visual and dialog queues on top of the music to keep me on rhythm. The minigames depict Cadence participating in activities like a Yoga class, meditative breathing exercises, and helping the NecroDancer assemble hamburgers. Each is a visual and aural delight. There are only five in total, enough to be an enjoyable distraction but too few to be a significant feature of the videogame.

Cadence’s progress through the Story mode is milestoned by boss battles. During her search for the source of the rifts, Cadence finds her friends harassed by mysterious forces that always turn out to be the doing of the evil creatures that once haunted the NecroDancer’s Crypt, all of whom have also been turned into trendy citydwellers.

Unlike the minigames, the boss battles are as forgettable as the Story mode itself. Each focuses on Cadence entering a one-on-one music battle. The boss makes several flourishing movements that represent the timing and direction I must press on the directional pad to make Cadence move out of the way of their attack. Successfully dodging enough attacks leaves the boss vulnerable to counterattacks which are also activated by precisely timed button presses. It’s a serviceable idea that has no staying power. I forget these supposedly titanic clashes as soon as the final cutscene has ended.

Rift of the NecroDancer’s modification of the familiar rhythm/music gem board with monsters that dance between rows in time to the music is ingenious and the best idea introduced to the genre since plastic guitar controllers. My complaints are mostly peripheral. I wish there were more songs. I wish there were far more minigames. I wish the Story mode wasn’t so insubstantial. These do nothing to detract from the incredible ideas built into Rift’s core design. Looking at its gem boards from a distance, it looks ordinary, a baffling deviation from Cadence’s dungeon-crawling roots. After playing it, I believe if Cadence wants to stay in this new, more contemporary world forever, fighting monsters with strums from her electric guitar instead of lunges with her shovel, I’d be just fine with that.