Wavetale is difficult to categorize. It resembles a 3D platformer with simple button-bashing combat, but to describe it only in terms of jumping, double jumping, grappling between ledges, and fending off monsters with a blunt object would omit one of its most noteworthy features. I play as Sigrid Skagerak, a young woman living on the ruins of a city crumbled beneath a vast ocean following an apocalyptic war. Her life is a repressed one, restricted to an island lighthouse by her brilliant and domineering grandmother. Sigrid spends her days patrolling around the lighthouse for Sparks, docile gelatinous creatures who emit an energy that drives away Gloom, a toxic fog leftover from the war. Following an unusually dense assault from a Gloom cloud, Sigrid encounters a shadow beneath the ocean surface. The eerie creature mirrors her every move. When Sigrid stands on the soles of her shadowy reflection’s feet, she gains the power to walk, run, and even supernaturally glide across the ocean’s surface. Using her newfound mobility and independence, Sigrid sets out on a quest across the submerged city of Strandville to rid her world of the Gloom. This goal crosses her path with the Dirty Paws, a remnant still intent on waging the lost war against the world’s few survivors who always appear in the Gloom’s wake.

Sigrid’s ability to walk on the ocean surface, enabled by her symbiotic relationship with the mysterious shadow, is what makes Wavetale unique. With no needed prodding or enabling of any special feature, Sigrid may step off dry land and onto water as easily as stepping from stair to stair. The ocean water still behaves like water; it realistically crests and plunges with roiling waves, creating sliding masses of churning hills upon which the young heroine may glide up and down.

An even more impressive power is prompted by holding down a button. This directs Sigrid to plant her left foot forward and bend her knees, and by some unexplained locomotive power, she slides along the water’s surface in defiance of water tension, friction, gravity, and all other kinds of physics. This sliding power is not only a great way to get around, outstripping even the boats other survivors use to travel Strandville’s ruins, it is also leveraged into Wavetale’s most spectacular and memorable set pieces.

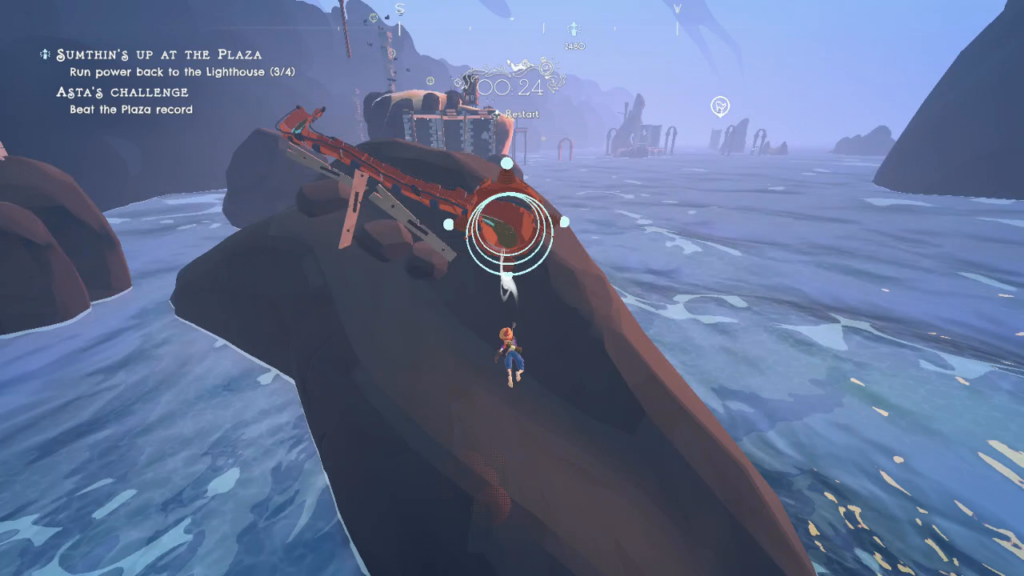

The survivors of the war have set up communities on the ocean’s few remaining islands, connecting their sparse settlements by narrow channels of safety through hazardous Gloom clouds. By some amazing coincidence of postapocalyptic destruction, these channels are dotted with ramps, chutes, and platforms that create the perfect playground for Sigrid to string together her waverunning powers with impressive daredevil acrobatics. Sigrid is a pioneer in a new kind of extreme sport, the only one who can do it through her connection with the aquatic shadow, and one on which the fate of the world is at stake.

When Sigrid sets foot on the remains of Strandville where humanity’s survivors make their homes, Wavetale becomes a much more conventional 3D platformer. She has the basic toolkit I expect from these types of videogame and uses it to gather collectables that gate her progress through the narrative. She is able to jump and double jump to reach higher platforms, and unlike her new waverunning abilities, no character treats her power to kick off from thin air as unusual.

It is the sparknet Sigrid carries with her that truly gives Wavetale its distinct identity while she is away from the water. An elaborate loop of metal connected to a long rod, its state changes according to Sigrid’s needs. Commonly, it is an ordinary net she uses to capture Spark energy. Uncommonly, Sigrid can spin it above her head to slow her fall like the blades of a helicopter. As with her double jump, no other character comments on this, as though her wrists spinning like rotors with enough speed and strength to hold her aloft are mundane in this oceanic setting.

The sparknet’s most fantastic ability is also the one that gets the most use. With a thrust, Sigrid can compel the net’s strings to stretch out and latch onto objects, either pulling collectables to Sigrid or pulling her to a platform. This is key to completing the waverunning obstacle courses; Sigrid’s leap from the peak of a wave is enough to get her close to a chute or platform, but the sparknet’s grapple is what pulls her the rest of the way. At times, the grapple can be too powerful. It will sometimes lock onto a target much higher than I intend, pulling Sigrid past significant parts of level geometry in unintentional sequence breaking.

Sigrid’s sparknet makes no sense. It’s a mechanical marvel even more wonderful than her waverunning abilities, yet much more inexplicable. Waverunning is justified by Sigrid’s relationship with the shadow. No such explanation is exposited or implied for the sparknet’s impossible powers. It’s so versatile and so much fun to use that I’m not going to spend a moment complaining. It’s part of Wavetale’s toolkit for 3D platforming and doesn’t require any further explanation than that.

Most of what survives of Strandville is little more than rubble and crumbling towers, though a few features suggest the thriving metropolis that once stood there. Aside from her lighthouse home, Sigrid applies her platforming skills to the skeletal remains of a ferris wheel and a factory shell recognizable only by its surviving smokestacks, among other crumbling relics. Other structures were built after the war as the human survivors rebuilt their civilization. Ramshackle wooden additions are literally bolted to the side of stone and metal structures, spiraling up and down to create the space humanity needs to live and also the precarious landings that make 3D platforming fun and interesting.

If Wavetale’s imaginative movement abilities have a flaw, it’s how they are applied to a routine campaign. The steps of Sigrid’s quest quickly become ordinary and familiar. Travel to the next major destination, climb to the top of a few disconnected islands to gather Sparks, insert them into a machine that transfers their power back to the lighthouse at the map’s center, find and whack a random lever to compel the machine to work properly, return to the lighthouse for the next story beat, and repeat. There is little variation and even fewer surprises. It’s only in the story’s climax that the scenario design changes at all, and that’s to thrust Sigrid into a last obstacle course before the final boss.

Another disappointment is how often waverunning feels separated from Sigrid’s goals. The sparks she gathers to further the plan that will stop the Gloom and defeat the Dirty Paws are placed high up in towers in the populated areas of the world. Sigrid uses an impressive array of jumps, double jumps, and sparknet grapples to reach them. Rarely does she waverun. This power, the best designed, most fun, most visually distinct part of Wavetale and from which it derives most of its identity, is largely relegated as a way to get from Point A to Point B. It’s a glorified mode of transportation. A surfer Sigrid saves early in her adventure sets up a series of time trial obstacle courses for her to race across; here, waverunning is a minigame, a supplement and still not a center. Only when Sigrid escorts a fleet of pirate ships through a reef choked with Gloom does it feel like what makes her unique among Strandville’s survivors is part of the narrative and not something that happens in between its core beats. This moment is as exhilarating as it is fleeting.

Wavetale’s weakest spot is its combat. Wherever Sigrid encounters Gloom, she must contend with the monsters that sprout from it. There are some variations, but all Gloom beasts share a common appearance: A pulsating orb of black ooze out of which sprouts four slender limbs they use to skitter around like spiders. Each is adorned with a scowling face, dwarfed by their bulbous body, that has too many eyes and too many teeth, emphasizing their monstrous and alien nature. They are simultaneously ridiculous and menacing.

Combat is not difficult. Sigrid’s versatile sparknet is once again her most useful tool. She bashes it like a club against Gloom beasts as hard and as often as I can bash the button that controls her swings. The beasts fall quickly, silently popping like bubbles. Some beasts are armored and take a few extra hits before they go down. Others have fashioned bits of metal into horns and charge at Sigrid like bulls. They are easily avoided. Monsters simply aren’t dangerous. When they do hit Sigrid, they take away a small portion of her life bar, which regenerates if she can go a few seconds without taking further damage. There is an infinite lives accessibility toggle in an option menu, but I never use it. Wavetale’s combat isn’t challenging enough to justify its existence. Even young children will have little difficulty dispatching Sigrid’s foes.

Sigrid also encounters Gloom beasts while waverunning. These are much more interesting, if not more difficult to defeat. They have the same bulbous bodies as their cousins, but attached to long and spindly legs that suspend them dozens of feet above the ocean’s surface. These features let them flit around the ocean like water striders. They attack by spitting globs of Gloom at Sigrid, though this is only dangerous if I try to ignore them. Sigrid overcomes their height advantage by weaponizing her sparknet’s grapple ability, transforming fights against them into a satisfyingly cinematic experience, if not much more difficult than standard Gloom beasts.

The final creature from the Gloom that Sigrid faces are the serpents. These colossal foes seem to be drawn to Strandville’s few populated areas. They are so massive that Sigrid’s sparknet is unable to harm them. They can only be driven off. Sigrid accomplishes this by climbing up their undulating bodies, utilizing all of her abilities to leap up between platforms and hooks driven into their woolly sides. The Gloom serpents are Wavetale at its most arresting and exciting. It’s little surprise that they capstone each leg of Sigrid’s quest in lieu of traditional boss fights.

When Gloom overwhelms a space, any people caught there become enveloped in oily black bubbles. The effects this has on the person are left up to my imagination. I never get the chance to find out since Sigrid may free them with a few whacks from her sparknet while she gathers Sparks.

Once freed, these people ask Sigrid for further help. Mr. Nelson, an engineer, asks for hammers so he and his son can repair a spark transmitter. He wants four, one hammer for each of their hands. A jeweler named Daisy has lost her dogs, her only companions since her family perished in the war. Every single one of these requests is a transparent fetch quest, requiring little more of Sigrid than to travel to where the person’s lost object or person is, then report back to them. Only Wavetale’s wonderful traversal systems makes this remotely appealing.

There is no formal journal or menu to track sidequests. Instead, they appear as a checklist in the corner of the screen, and only when Sigrid is in the region in which that sidequest appears. There are also no markers on the map showing where a quest objective is found or where the person who wants it is waiting. Objectives are never far from where the sidequest begins, but if Sigrid wanders away and returns to finish the job later, she may have to aimlessly circle the area for many tedious minutes to pick up the trail again. It’s best to do sidequests as soon as Sigrid encounters them if I plan to finish them all.

Sigrid initially encounters these sidequests in her first proper trip away from the lighthouse into the most densely populated area of Strandville. There are at least five sidequests to be completed here and probably more. It is difficult to tell what Sigrid has and has not done because of the peculiar way Wavetale tracks sidequests. With each new region she visits, the number of available sidequests is reduced. By the final area, there is only one, an obligatory trip across a sliver of water to gather medication for a survivor named Siobahn. It takes only seconds to complete. As I scrape these last dregs from the bottom of the sidequest barrel, I wonder at their purpose in Wavetale’s broader whole. There’s a lot of heart in Wavetale’s platforming and storytelling. Little is found in its sidequests.

The diminishing number of sidequests doesn’t matter much. The only reward for completing them are stashes of mini sparks. Too immature to power Strandville’s anti-Gloom technology, these are instead used as currency at Mr. Baine’s traveling shop. Sigrid can change her appearance on this boat, dying her hair into a variety of colors, swapping the pattern and style of her clothes, and adopting an array of hats and other headgear. The selection is surprisingly vast and grows even larger as Sigrid progresses through the narrative, presenting far more options than I will ever be able to use in Wavetale’s four-to-five-hour length. I appreciate the opportunity to customize Sigrid’s look with my own personal flair.

Everywhere Sigrid travels in Strandville, she is confronted with many different kinds of distrust from the people who live there. Strandville’s core residents, especially its haughty mayor, dismiss Sigrid for her youth. Later, Sigrid seeks out a group of engineers who can assist with building an anti-Gloom machine. They are reluctant to help because they remember how their guild was treated before the war; even long after civilization has collapsed, the working class remembers their mistreatment. Late in the story, Sigrid discovers a hermit who has isolated himself in a distant section of Strandville out of shame for a tragedy in his past. Her ability to move past her distrust of this man is key to resolving the conflict and cements her as the story’s hero.

Sigrid even encounters distrust in her own family. Doris, her grandmother, doesn’t trust Sigrid to be safe out on the ocean. It is only the urgency of the Gloom situation coupled with Sigrid’s unique new powers that causes Doris to begrudgingly allow her granddaughter to leave the lighthouse. Even with these minor improvements in their relationship, Wavetale’s climax is centered not around the Gloom, not around the Dirty Paws, but around Doris’ inability to trust her granddaughter because of her fears about what could happen. If trust is not the center of Wavetale’s narrative, then fear is. It does a good job communicating these ideas without underlining them, resulting in a satisfying and bittersweet conclusion that ties up all its loose ends.

Wavetale is a great example of style winning over substance. Why Strandville’s destruction perfectly carves waterbound passages where Sigrid’s waverunning powers thrive is unexplained. Her marvelous sparknet is unexplained. I question none of this because Sigrid’s skills and tools are too much fun to use. If their impossibility were examined and collapsed, Wavetale would become a much less fun videogame to play. I only wish waverunning was better integrated into the overall scenario. As fun as it is zooming through Strandville’s specialized corridors, it ultimately feels more like a way to travel between goals than to actually accomplish them. Tedious combat and forgettable sidequests further make me wish that Sigrid was waverunning instead of wandering around swinging her sparknet. A heartfelt story with a clear message that lasts only as long as it needs helps bring my feelings towards Wavetale back around to warmth. It’s flawed, but there’s a lot to admire as well.