Europa is a linear 3D platformer that follows a boy’s journey across a lush moon to a flying island. I play as a boy named Zee whose father, Adam, has recently died. At the story’s outset, Zee reads from Adam’s journal, its words exhorting his son: “Come to the Island if you ever get lonely. Come here, and think of me.” The Island is visible in the distance from Adam’s grave, floating far beyond Zee’s rustic cottage home next to a pair of grey twin peaks. Strapping a rocket to his back, Zee sets out on a mission to reunite with his father on the Flying Island. His journey takes him across the surface of Jupiter’s moon Europa, terraformed into a green paradise tended by robot herds called Gardeners. Along the way he passes through the rubble of a civilization that presents a mystery: How did Europa get this way, and where are the people who built it?

Most of Europa’s design is built around how Zee moves across its three-dimensional environments. Jumping is unconventional. Pressing the jump button does not prompt Zee to immediately jump. It prepares him to jump, which he will not do until I release the button. Holding the button for a moment charges the rocket on Zee’s back with kinetic energy. Releasing the charge launches Zee a short distance upwards and over many of the small obstacles that block his path.

These short bursts do not need to be the end of Zee’s ascension. Europa is dotted with pools of Zephyr, a blue substance that powers many of the machines found there. Moving near a Zephyr source automatically hoovers it into the rocket’s fuel tank where it may be used to propel Zee even higher. Once airborne, I may slow Zee’s return to the ground by holding down the jump button once more, causing him to spread his arms and glide as though suspended from strings.

The rocket’s use of Zephyr fuel is not efficient. Holding down the propulsion button will carry Zee high into the sky. It will also drain the rocket’s reserves in seconds, keeping Zee grounded until he discovers another Zephyr source to absorb. Claiming crystal stars hidden around Europa expands the rocket’s Zephyr tank, though even at maximum levels it will still burn through its supply in seconds. Many platforming scenarios take advantage of this limitation, setting themselves in locations barren of Zephyr and even siphoning what remains in the rocket’s tank to prevent Zee from simply blasting over every obstacle in his way.

Sometimes the opposite is true and Europa presents an area abundant with Zephyr, allowing Zee to cut loose with his rocket. Alternating short rocket bursts with long stretches of gliding carries Zee a surprising distance. It isn’t flight, but it’s the next best thing. It’s a wondrous and sadly infrequent feeling when an area abundant with Zephyr allows Zee to soar through at exhilarating speed, heedless of what may be on the ground to block his passage.

The terraformed Europa is a splendidly green and verdant world. Arching hills slope down into deep valleys—perfect for gliding down into—filled with trees, rocks, and ponds. These valleys contain the crumblings ruins of a deserted civilization built from warm sandstone and ruddy clay. Their sunny surfaces contrast pleasingly against the green plantlife that overgrows the shattered stonework. None of these elements feel stock, as though a small number of objects were designed then reproduced endlessly to create the illusion of a verdant world. Each tree, shrub, rock, and ruin feels like it was made by hand and placed with intention. All of this is created with a graphical style that makes each frame look like a watercolor painting. The effect is particularly striking when seen from a distance.

While these landscapes are beautiful to behold, they suffer from lacking variety. Only a handful of Europa’s fifteen chapters deviate from the template. As Zee approaches the mountaintop that will allow him to reach the flying island, the greenery is replaced by snow. His path detours through the interior of the mountain where towering lichen and ivy grow upward from the floor, sheltering invertebrates that undulate to propel themselves around the room. It looks exactly like a seafloor ecosystem, but this cave contains no water at all. It is the most haunting and alien location on Europa, its existence a complete mystery next to the fields formed and cultivated to look like Earth in summertime.

At frequent points along Zee’s path to the Island, his progress will be stopped by a sealed door or force field. To continue on he must solve a nearby puzzle which will open the path. These puzzles are simple. Most often, Zee must find braziers hidden around the area and activate them with a pulse of Zephyr energy. Other puzzles task him with searching the area for hidden energy orbs and delivering them to the sealed door. There is functionally zero difference between the torch hunt puzzle and the orb hunt puzzle.

A third puzzle variety, and Europa’s best, finds Zee standing on blocks above a pit. Emitting energy pulses causes the blocks to rotate clockwise around each other. If any blocks collide with another surface, then they all disappear, Zee is dumped harmlessly into the pit, and the puzzle resets. Zee must mindfully direct the blocks into specific positions that will unseal the path forward.

These puzzles exist as purposeful speed bumps. Without them, Zee’s journey to the Island would be an uninterrupted scenic tour, wonderful to look at and occasionally fun to navigate, but with few interactive elements beyond moving forward and jumping over obstacles. The puzzles create a reason to stop and spend a few minutes in each environment instead of zooming across Europa in under an hour. The puzzles aren’t difficult. They aren’t even interesting. They do the necessary job of ensuring Europa’s length creeps into the three or four hour mark.

If I were tempted to steer Zee away from Europa’s speedways and speedbumps, I would find my efforts stymied by its rigidly linear design. The methods it uses to keep me on its designed path is crude and reveals Europa’s artificiality. When I try to steer Zee outside of its designed spaces, the screen fades to white—helpfully hiding from my eyes that nothing exists just over the hills he tries to climb—and strong wind gusts force him back onto the linear path. Once Zee is pointed back towards the Island, the image sharpens back into colors and shapes. At other times, Europa makes the simpler and blunter choice of putting an invisible wall in Zee’s way. The moon appears to be a playground. It’s really more of a highly decorated hallway, pleasant to look at, relaxing to traverse, and focused on shuttling its occupant to a single space at its end.

A more effective motivation to keep Zee pointed towards the Island comes in the form of the collectibles he can gather along the way. Zee is a talented artist and I can direct him to sketch pictures of the Gardeners, the robots that terraformed Europa and maintain its environment, into his sketchbook. There are also forty emeralds hidden around Europa, stashed away on top of the highest rooftops and sequestered in nooks and crannies. The constrained world design makes searching for them tedious. Many are hidden on rooftops and in caves that are only visible by pointing the camera back towards Zee’s cottage. It’s better than nothing at all.

The most significant and obvious collectibles are pages from Adam’s journal. These appear all along the path from Zee’s cottage to the Island, sitting out in the open and highlighted by a brilliant column of golden light visible from great distances. They are not intended to be missed. They serve as flags which mark every small and significant step Zee makes on his journey.

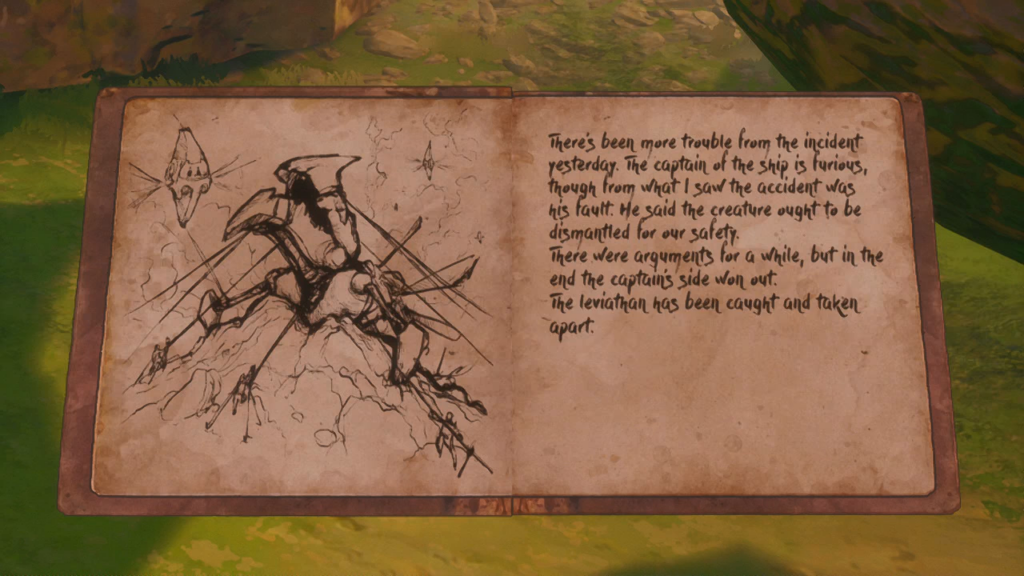

Adam’s journal is where Europa describes its backstory. Through his writings, I learn that he was one of the creators of the Gardeners, nanomachines who were sent ahead to terraform the moon in anticipation of humanity’s arrival. In a short time, the nanomachines evolved into robotic creatures, some as small as insects and others as large as whales which fly through Europa’s skies. When the humans reached Europa in their own ships, they immediately came into conflict with the Gardeners—immediately, as in, before they even landed their ships. This backstory, as described by Adam, is dreary and misanthropic, a dark contrast to the whimsical rocket-powered movement, cheery color palette, and Ghibli-esque imagery.

A later journal entry explains Adam’s relationship with Zee. The way it is written confuses me. The journal treats the detail as a revelation. Europa’s store page treats it as fact, revealing a key aspect of the character before I have a chance to purchase the videogame. It’s a detail that’s easy to presume. I may even deduce it by paying close attention to Zee’s character design when he is facing the camera. The narrative treats it like a twist when nothing else about Europa’s presentation or marketing does. It feels like an example of the left hand not knowing what the right is doing, squandering the one thing that might make me reconsider Adam’s poor evaluation of Europa’s human colonists.

Zee’s journey to the Flying Island ends with his discovery of the remaining human colonists asleep in stasis. Adam’s journal makes it clear that it will be Zee’s choice whether or not to revive them; the default ending makes his choice ambiguous. Based on what I hear from Adam, I feel like they don’t deserve this second chance at life, though his is a biased perspective. I feel dissatisfied by this conclusion. Beneath its bright exterior, Europa offers little to feel hopeful about.

Despite its four to five hour playtime, I have a difficult time with Europa. The increasingly bleak backstory Zee uncovers as he nears the Flying Island drains my desire to see his journey to its conclusion. When it does conclude, a lack of finality leaves me feeling dispirited. The way Europa plays is another, almost opposite matter. At its best moments, crossing the moon’s terrain is reflexive and meditative. The colorful visuals and sense of wonder at hurling Zee across valleys as though he was weightless should make me feel joyous and free. The story the game design tells and the story Adam’s journal tells cancel each other out, leaving me feeling ambivalent about the entire piece. Of all the videogames I’ve played in 2024, I struggle most with feeling anything at all about Europa.