Turnip Boy Robs a Bank picks up three days after the events of Turnip Boy Commits Tax Evasion when the mute, antisocial player character is recruited by the gangster pickle Dillitini to mount a heist on the Botanical Bank. This new premise imposes a new style upon the game design; where Commits Tax Evasion was a silly take on Zelda-inspired action and adventure, Robs a Bank is a twin-stick shooter. Dillitini’s seemingly simple plan quickly becomes complicated. The gigantic Botanical Bank is filled with inexplicable additions and its manager, Stinky the garlic bulb, seems to know all about Turnip Boy and his family’s criminal history. During multiple heists across many days, the crew works to unlock the treasure at the bank’s heart all while it becomes apparent that Turnip Boy will find much more than the riches hidden away by Stinky.

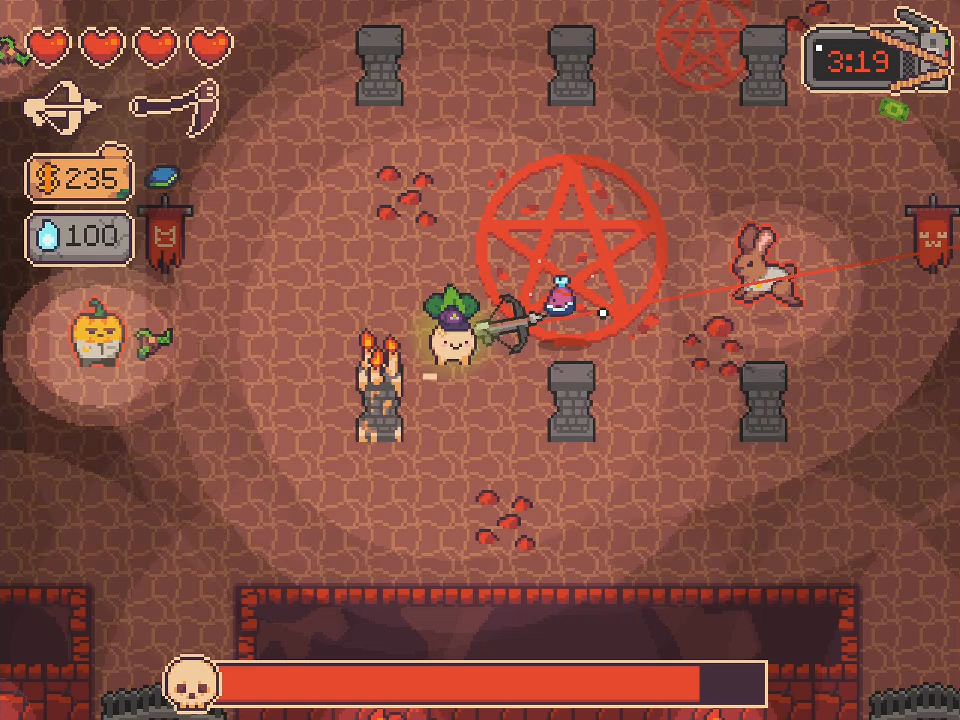

Turnip Boy arrives at the Botanical Bank by crashing through a lobby wall in a truck then jumping out pointing a gun. This immediately sets off the bank’s alarms, which the heist team’s tech expert Annie is able to jam for three minutes. Wherever Turnip Boy goes within the bank, this time limit ticks in the corner of the screen, counting down to the arrival of the heavily armed local police force. Turnip Boy must get as much accomplished within the bank as he can before escaping in the truck back to Dillitini’s hideout. He will return the next day, crashing through the same wall, running through the same rooms, and rushing against the same time limit.

Turnip Boy’s heists feel like they are trapped in a time loop, though this is just a feeling. Reiterative chaos is how this world works. Every day the bank opens, every day Turnip Boy robs it, every day the police wait a few minutes before they arrive to defend it, and every day everything the player character destroys, steals, or kills is restored as though the previous day never happened. It takes me about 30 days of this routine, or about four and a half hours total, to help Turnip Boy fully explore the bank and complete all the tasks inside its walls.

Turnip Boy’s quest in the Botanical Bank requires him to fully explore each of its four wings. Each has a unique theme and enemies designed to match.

In the ordinary offices of the bank’s south wing, peppers dressed in white dress shirts and whip out pistols made of wood when Turnip Boy draws near; these are presumably the “good guys with a gun” of United States myth who are as unsuccessful in this videogame as they are in real life. The west wing hosts an incongruous and inexplicable indoor forest. The ravenous snails, rabbits, and worms that tried to eat the protagonist in Commits Tax Evasion have taken refuge here. The posh mahogany-paneled east wing would seem to be home to executive offices, but the eerie candles adorning every surface and skeletons chained to walls give it the atmosphere of a haunted castle. The angry slimes, upturned ice cream cones, and howling candies that protect this space add to its macabre atmosphere, but try not to think too much about where skeletons come from in a setting where humans do not exist.

Only the bank’s north wing has enemies that feel out of place. It is a delivery dock filled with toxic chemicals and a pervasive darkness. Though it shares these features with a primordial cave, the enemies encountered here are gun-toting security peppers. The creatures that do fit in there, skulking goblins living in patchwork tent villages, are friendly and ask for Turnip Boy’s help.

When Turnip Boy’s alarm timer runs out, the bank fills with police who rappel down ziplines into the middle of every room. In keeping with the level of sophisticated humor exhibited in Commits Tax Evasion, these cops take forms which double as puns. Strips of bacon swing at Turnip Boy with batons. Peaches, noted for their fuzzy textures, charge through the bank hallways with automatic rifles. Large donuts wield a combination of weapons, spinning them around their bodies with invisible hands. Turnip Boy Robs a Bank hopes all of these allusions make me laugh. They do not.

Turnip Boy carries two weapons of my choice to attack the bank’s defenders. I control him with a typical twin-stick control setup. One input, the left joystick or the keyboard, controls where Turnip Boy moves, while the other input, the right joystick or the mouse and cursor, controls where he aims his weapon. This gives him all the nimbleness I expect from a twin-stick shooting protagonist, able to navigate away from enemy attacks while directing his own back at his attackers.

Weapons come in ranged and melee varieties. Turnip Boy begins a heist wielding a selection of plain guns taken from Dillitini’s hideout, such as a pistol or a shotgun, and later on even a bazooka or laser. He can also loot guns dropped by enemies in the bank. These tend to be much more interesting and powerful, like a cactus that shoots a burst of spines or a giant glove that fires projectiles from its fingers. These guns also have limited ammunition. Though some enemies drop more ammunition when they are killed, a gun will inevitably have to be replaced when its ammo reserves are emptied. Melee weapons do not need ammunition but necessitate close-range combat and are often slow to swing. It feels wise to carry one ranged and one melee weapon, though this is not forced on Turnip Boy.

Sometimes the spray of projectiles coming towards Turnip Boy is too dense to be run through. In typical twin-stick shooter fashion, he is equipped with a dodge for these situations. The dodge empowers the player character with a split second of invulnerability, letting him pass harmlessly through an otherwise solid wall of enemy fire.

While Turnip Boy does get a lot of use out of the dodge, particularly against the boss fights which often demand it, I find it is often unnecessary to use it. Taking an all-out offensive approach against most enemies proves more effective than defensively avoiding their attacks. The dodge is important but is not as foundational to the mechanics as I expect from a contemporary twin-stick shooter.

Another particular weakness of the design is the weapon variety. During one of Turnip Boy’s early bank heists, he comes across a room where a living flame named DJ Sizzle offers a deal: Gather souls from the bank’s occupants using a special scythe, the Soul Sampler, and Sizzle will gift Turnip Boy with copies of his music. The Soul Sampler is absurdly powerful, and being a melee weapon, it does not need its ammunition refilled. Turnip Boy spends most of the rest of our time in the bank using the Soul Sampler and not just because it is the only way to earn all of DJ Sizzle’s extra music tracks. I am never given a reason to stop.

There’s a clear hierarchy in weapon usefulness and the Soul Sampler sits near its top. When Turnip Boy does try another weapon, I am dissatisfied with the results and soon return DJ Sizzle’s singular scythe to the player character’s invisible hands.

Not every non-player character Turnip Boy encounters in the Botanical Bank is hostile. Many have requests like DJ Sizzle. A starfruit artist needs to collect payment for a commission from a popular streamer. A lime needs signed divorce papers retrieved from her husband. A carrot needs ethical advice about the abomination they are creating from random body parts.

These are all boring and routine fetch quests which require finding the quest giver at Point A, speaking with another NPC at Point B, then returning to Point A to complete the quest. The only thing that makes them interesting is the NPC that must be spoken with is not marked on the map. Turnip Boy must search the bank for them. Quests may thankfully be completed across multiple heists. If they prove too cumbersome or irritating, I may even ignore them. Quests reward achievements and new hats for Turnip Boy to wear but give no material advantage. There is no penalty for ignoring them.

I may be tempted to ignore quests because of where some of the NPCs are found. The Botanical Bank is mostly static. Its four wings and the bosses which capstone them always appear in the same cardinal points and these are the spaces where most NPCs wait for Turnip Boy to visit.

Each wing also features elevators and the rooms they lead to change on each visit. This is explained as one of the bank’s security features. The first time Turnip Boy finds an elevator, it may lead to an office where he can navigate through a hallway of defensive lasers that protect a vault. On the next visit, the elevator takes Turnip Boy to a plane of hell where he can compete in a gladiatorial arena hosted by a demon. On a third visit, the elevator ends in a dank basement where a mushroom-worshiping cult gives new hats for killing certain numbers of specific enemies.

These instances of quest-giving NPCs are where the elevator randomization becomes a headache. Finding the lime’s soon-to-be ex-husband skulking somewhere in the bank should be the hard part of completing her quest. Returning the divorce papers may prove more difficult when it takes many heists for the elevator that leads to her office to appear again. I get it done through sheer doggedness. I am sympathetic to those who give up on the idea the first time they return to the elevator shaft and it no longer takes them back to the quest giver.

Turnip Boy’s most immediate task on each bank heist is to steal money. He can begin looting as soon as he crashes through the lobby wall. Turnip Boy can lift the terrified bank patrons and workers above his head to shake dollars and coins loose from their bodies which are hoovered automatically into his pockets. He can smash glass cases that appear across the bank, adding jewels and objet d’art to his collection. Whatever money and valuables Turnip Boy is able to take back to Dillitini’s hideout, or half of whatever he has accumulated if the bank’s defenses or the attacking police can drain his hit points, is added to his total riches.

Turnip Boy does not steal money and valuable objects from the bank for no reason. Between heists, he visits Dillitini’s hideout, a nondescript warehouse where the crew prepares for their next mission. Speaking to the NPCs here allows Turnip Boy to purchase upgrades and items using the riches he steals from the bank.

Most of Turnip Boy’s purchases are made at the Robo-Roids shop. Run by Robo-Rafael, a cybernetically reconstructed turnip who worked for Mayor Onion in Commits Tax Evasion, he sells dubious vitamins and injections which improve the player character’s statistics and other variables that affect the heist. Whey increases Turnip Boy’s melee damage, candy hearts grants him an additional hit point, and steroids increase the damage of projectile weapons… somehow. He also sells other useful items, like a larger money bag so Turnip Boy can carry more loot and a better jammer so it takes longer for the police to arrive.

Turnip Boy can also spend his stolen money on the Dark Web. Accessed through a web browser, the Dark Web sells quest items that are needed within the bank. Some of them are practical items that see repeated use, like a laser pointer that can cut open safes, letting the stacks of cash inside be stolen. Most items are needed to bypass specific obstacles and are only used once.

Turnip Boy encounters these barriers almost right away with a line of statues blocking the south wing’s access to the rest of the bank. A pickaxe that looks suspiciously like it’s been used to break voxels in the past can do the job. The only place to buy it is from the Dark Web. Turnip Boy encounters many more obstacles where his progression through the bank comes to a halt until he returns to Dillitini’s hideout and drops a huge amount of money on the next figurative key to open the current figurative door.

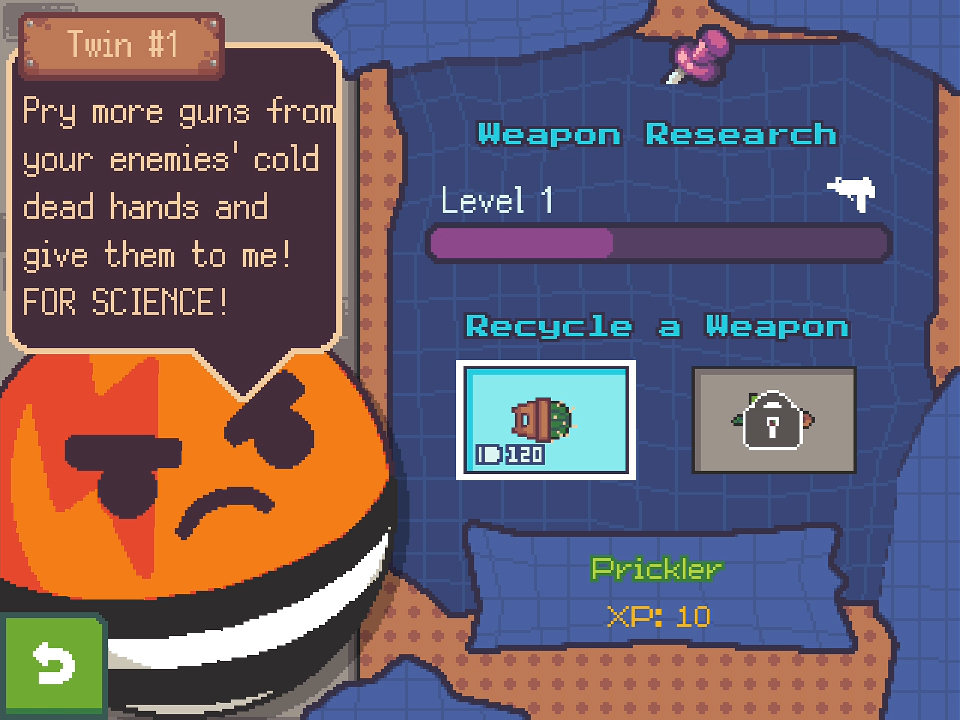

The final way to improve Turnip Boy does not use money at all. Twin tangerines are in charge of arming Turnip Boy for each of his heists. At the start their selection is poor, only providing a pistol and the sword Turnip Boy wielded in Commits Tax Evasion. Their armory stock can be expanded by delivering the weapons enemies drop in the bank. The more rare the weapon, the more points Turnip Boy earns towards the next weapon unlock.

This system creates an interesting tradeoff. The guns the twins provide are generally weaker than ones picked up in the bank. They also have infinite ammunition and a fresh one is provided to Turnip Boy at the start of each heist. At first, giving up a cactus gun to unlock an uzi feels like a dubious tradeoff. As Turnip Boy earns more points and unlocks guns with higher attack power and greater accuracy for the twins’ armory, giving up looted guns begins to feel like a better deal.

In my review of Turnip Boy Commits Tax Evasion, I questioned the purpose in choosing to skewer taxes and the government as a whole. I concluded that its humor was so broad that it did not express any actual ill will towards these institutions. It mocks taxation and the government because they are easy targets. I also examined Turnip Boy’s characterization and found him to be an off-putting player character.

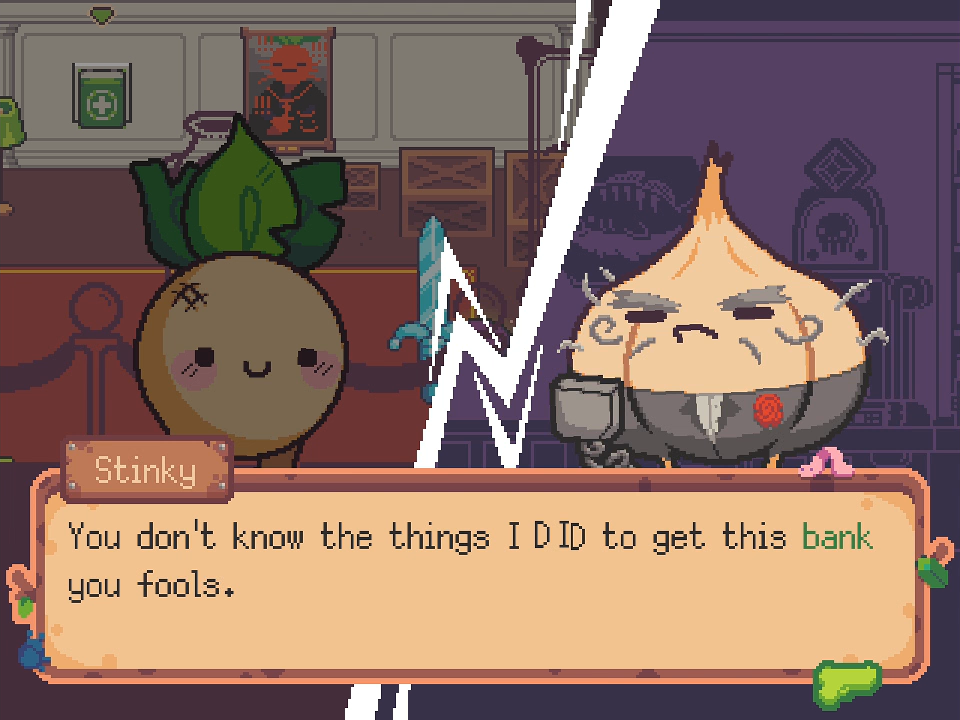

I do not find myself grappling with either of these questions in Turnip Boy Robs a Bank. Turnip Boy’s new goal is so obviously criminal and pointlessly violent that I cannot discern in it even a fragment of social commentary. It would even have been easy to do so by making Stinky an openly malevolent force whose greed is at odds with the region’s recovery. Instead, Stinky is an obviously corrupt and criminal character, though in non-specific ways. Instead of involving himself in the conflict, Stinky taunts Turnip Boy over an intercom from the safety of his office. He is a weaker antagonist than Mayor Onion.

Turnip Boy’s own characterization is weaker as well. I feel much less unease about his behavior, despite his more openly despicable nature, because he barely has characterization at all. His habits of destroying any documents he gets his hands on and passively staring at anyone who interacts with him are now absent. He is much more of a cipher in this videogame, a conduit through which I can rob a bank and kill the things that try to stop me. He is a less disturbing and less interesting character.

Turnip Boy Robs a Bank is a decent twin-stick shooter. It’s not groundbreaking but it keeps me entertained for four to five hours. The gradual buildup of Turnip Boy’s power using the money and guns he steals during his heists is rewarding and the videogame is short enough that I can experience major shifts in strength in a short play session. Where it feels weak is its sense of humor and characterization. I was skeptical of these aspects of Commits Tax Evasion, though I admire it for taking big swings. Turnip Boy Robs a Bank feels much safer in its sense of humor. It’s a fine videogame and a good way to spend an evening.