Harold Halibut is a narrative videogame that utilizes the distinctive and time-consuming stop motion animation technique to create its sci-fi world and colorful characters. The story is set aboard the interstellar ship Fedora. Launched to carry a select group of humanity away from the certain nuclear extinction brought by the Cold War, the Fedora’s crew traveled for two hundred years and multiple generations to a distant planet only to discover their new home had no land and a toxic atmosphere. Before the crew could come up with a new plan, solar storms sent the Fedora crashing into the planetary ocean. For more than 18,250 days, the Fedora’s survivors have lived in the submerged ship, safe and alive, but trapped deep in the ocean of a poisonous and alien world.

The story takes place over the course of three months in which the Fedora experiences a number of curious events. A new communication buoy receives a message from the Earth they assumed was destroyed. An unexplained energy shortage causes chaos in the ship’s tube-based travel system. An illusive rebel group, the Lightkeepers, undermines the Fedora’s ruling authority, the All Water Corporation. The crew’s most brilliant scientists propose competing plans to free the ship from its ocean prison and launch it back into space. And for the first time in over fifty years since the crash, the Fedora’s crew encounters sentient life native to the planet. At the center of all this is a low-ranking laborer named Harold Halibut. His participation in these events changes his life and the lives of everyone living on board the waterbound spaceship.

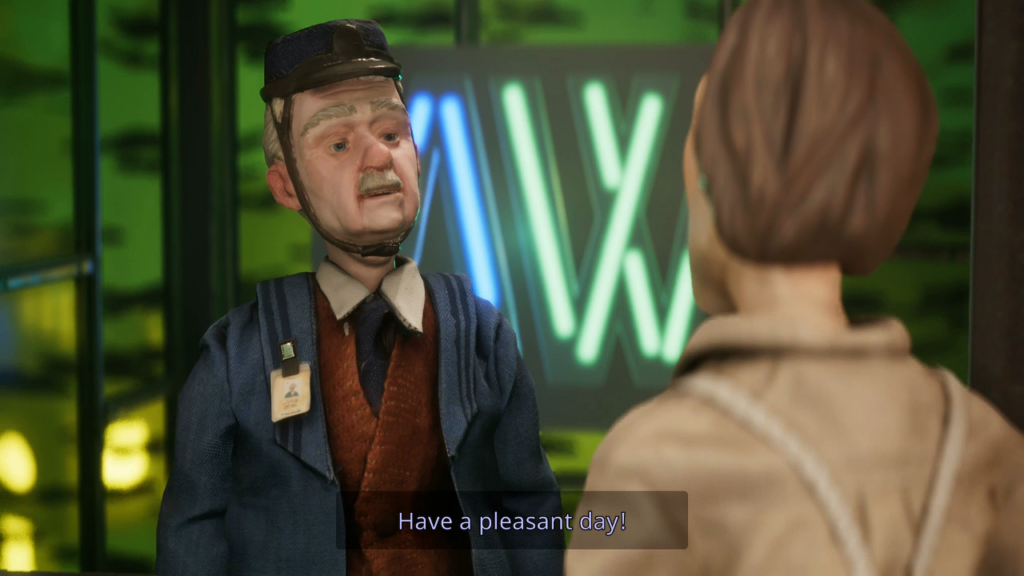

The characters who live on the Fedora are lively and diverse, encompassing a variety of personalities, body types, and skin tones which are all enhanced by great designs. Brenna Casselchop’s design is a particular standout. Her bow-legged stance and neat black pant suit aren’t unusual. It’s her flat-top haircut and round, red eyeglasses that make her memorable, a fashion disaster that makes her look like a character from a 1980s music video crawled out from a TV screen and took a position as CEO of a sketchy extraplanetary corporation. Other memorable character designs include Rafi, a sullen, freckle-faced boy with a giant afro that has the texture of popcorn, and Chris Tinnerbaum, a huge and muscular man with long, bleached-blonde hair who wears a tropical robe, underwear, and nothing else. He is the Fedora’s schoolteacher.

Harold himself seems to be a deliberate contrast to his friends and coworkers in design. Where the other Fedora crewmembers stand out through distinctive garb and unique body shapes, Harold is aggressively bland and ordinary. He wears humble, earth-toned clothes on his lanky body and his brown hair atop a narrow, almost elongated head is styled with a common part.

Harold has lived his entire life on the submerged Fedora where his official duties seem to be delivering messages and performing manual labor for the ship’s scientists. This lowly status causes his crewmates to take him for granted, but Harold occasionally shows depth that catches them by surprise. When Cyrus Soleil, an especially pompous scientist, explains his plan to launch the Fedora back into orbit, Harold correctly compares it to the biological propulsion techniques of cephalopods, to Cyrus’ audible astonishment.

Harold is not unintelligent, but he is simple. At one point, Professor Mareaux, his supervisor and landlady, proclaims that the All Water Corporation leadership expects the Fedora’s scientists to jump on command. Harold’s immediate response is to ask how high they should jump. He is the everyman among a self-contained, self-sustaining society of eccentrics and geniuses, able to understand the delicate and incredible scientific marvels that keep him alive in an alien ocean, but unable to take the initiative to change his circumstances. He is always at the mercy of forces greater than himself.

The Fedora itself is equally distinct as the characters and even more detailed. Before beginning Harold’s story, the videogame’s opening moments take a few minutes to introduce me to the Fedora in montage. A fish swims through the deep ocean until it reaches the ship, a bubble of light in the depths of the ocean where sunlight cannot reach. Instead of a solid craft, the Fedora’s different compartments spun around a central propulsion unit, tethered to and allowed to rotate around it. Now underwater and mostly disconnected from the rocket, these compartments are connected by a pressurized tube network that carries the crew from space to space like hamsters in an aquatic cage.

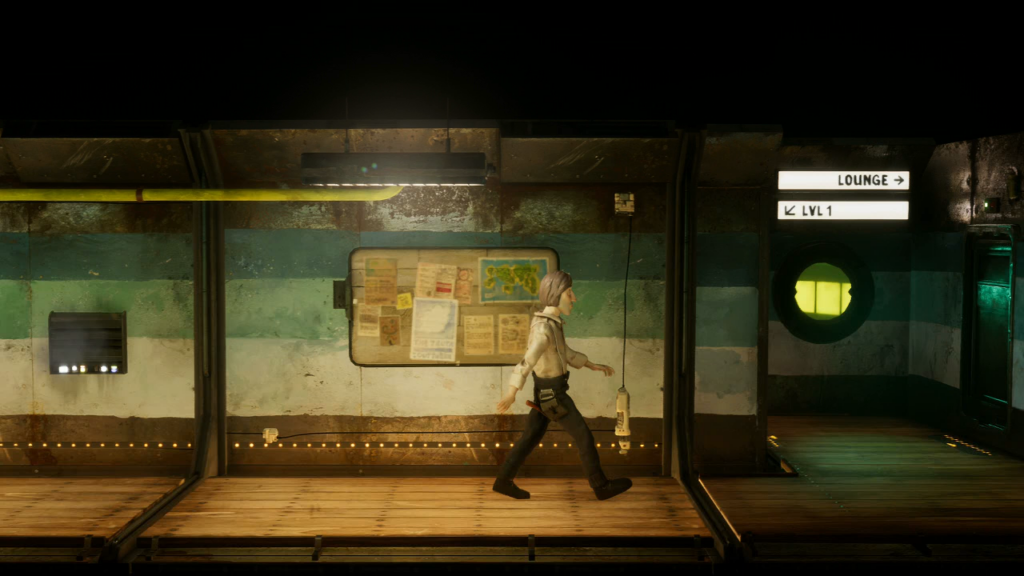

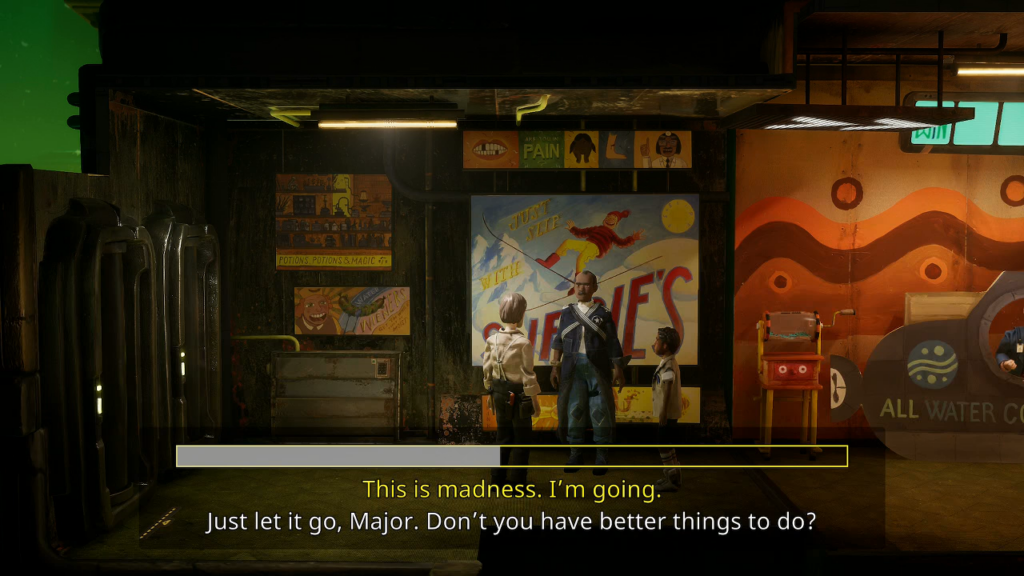

Over the course of the story, Harold is called to different locations around the Fedora. It’s easy to deduce what function these compartments serve based on their names. The Lab District is where the Fedora’s scientists conduct their research. The Energy District extracts resources from the ocean to power the Fedora. The Agora Arcades are an especially thoughtful location. It contains the Fedora’s social spaces, including an automated bar where Harold can eavesdrop on a gossipy couple discussing the plot’s latest developments and a shop where he can play simple third-person flying videogames. Its name and construction also evokes the Greek Agora, a public gathering place, and an Arcade, a space supported by arches. When events call for the crew to assemble as one, they meet in the Agora Arcades, and its structure is built like a giant terrarium supported by firm metal arches.

Places don’t just exist in Harold Halibut. I can see that thought and care are put into their imagination, that each has a meaningful purpose for the Fedora and its crew even if the protagonist isn’t called to spend much time within them.

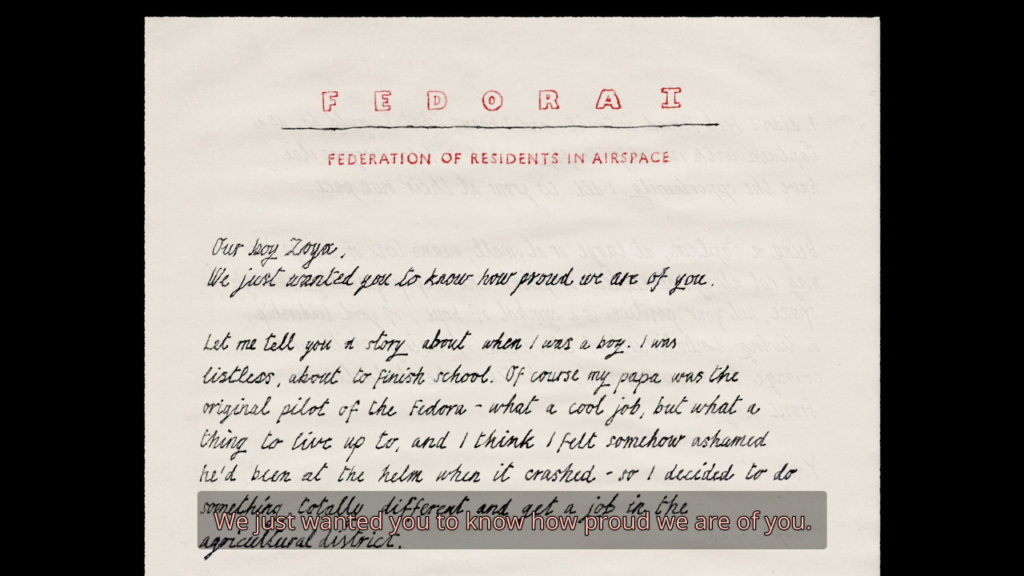

Even more impressive are the finer details I see when I stop for a moment to scrutinize the environment. By reading the words printed in the heading of an undelivered letter, I can deduce that they are truncated to give the ship its otherwise inexplicable name—Federation of Residents in Airspace, or FedORA. Nothing draws my attention to or spells out this abbreviation. It is left to me to notice these details and deduce their meaning.

Other environmental details also gain more meaning upon closer examination or reconsideration. In the Social District, a large empty room sits outside the ship’s only schoolroom. I deduce from the disco ball hanging from its ceiling that this room is used for parties long before Harold actually attends one near the story’s conclusion. When visiting Agora Arcades, Harold has the opportunity to try out a crude skiing simulator in Slippie Schlipmeier’s shop. What at first seems like a slapstick gag and a moment to earn an achievement takes new meaning when the story approaches its climax.

At most other points in the story, Harold can sit down in the Lab District’s dingy kitchenette to watch episodes of Sonsuz Ask, a Turkish telenovela. Its plotlines are endless and repetitive, its production values non-existent, and Chris—a big fan—insists it’s worth sticking with it if you can power through the first couple dozen seasons. It’s apparent that what little culture the Fedora’s crew has retained from Earth is of low quality and they have been forced to make their own. Back in the Arcades, Harold can indulge in some of this culture by stopping to watch a one-man show or a barbershop quartet perform on its stage. The Fedora teems with hidden activity and minute details if I am patient enough to look and wait for them.

These great character designs and thoughtful details are made all the more impressive because all are ostensibly captured with stop motion. This animation technique uses highly articulated puppets in elaborate miniature sets to create their worlds. By photographing dozens of images, each of them slightly changing the puppet’s face and body, and playing them quickly in succession, an illusion of movement is created. Stop motion animation is time consuming and expensive, so its success in mainstream films has largely been limited to specialist studios like LAIKA and Aardman Animations. In a videogame, to the best of my knowledge, stop motion animation has not been used to this extent since the 1990s 16-bit videogame Clayfighter.

The result is Harold Halibut is stunning to look at. While guiding the player character through the Fedora, I see the world from a fixed, side-on distance as though I am observing ants in an ant farm. These perspectives recall the scene-setting montages from the films of Wes Anderson, himself no stranger to stop motion animation techniques. This kind of perspective doesn’t bear mentioning in other videogames. It’s standard. It’s expected. When it’s mixed with stop motion animation here, it feels novel and notable again.

The way Harold swings his arms as he ambles through the Fedora’s hallways would be a simple walking cycle that, again, wouldn’t bear commenting in most other videogame reviews. Here, knowing every frame of that animation is painstakingly photographed from every possible angle, it feels like showing off. If anything, the animation is too fluid, lacking stop motion’s signature jerkiness.

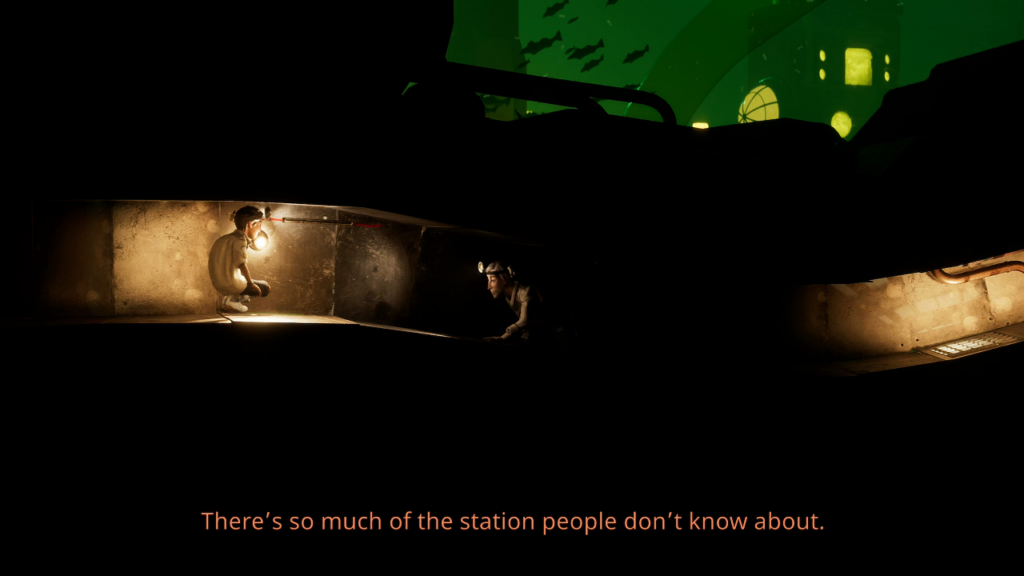

More stunning than the animation is the lighting. Harold Halibut takes full advantage of the ship’s powerful lamps and beacons to create dynamic light sources. When Harold stands between a light and another character to speak with them, half of his face is brilliantly lit and the other half falls into deep shadow in a way that’s breathtaking to witness. The deep sea environment is taken advantage of to create haunting scenarios. Most areas of the Fedora are well lit, but when Harold ventures into the ship’s less-traveled access corridors or travels outside the ship in a submersible, then figures turn into silhouettes backdropped by the sickly green of the deep ocean.

The full-body shadows are disappointingly inconsistent. In a few locations, lights cast stretched and distorted shadows from the characters onto the walls and ceilings. In other places—especially high traffic areas where I have full control of Harold’s movements—character shadows are barely visible at all. The more specialized an area is in the plot, the more likely I am to see an incredible interplay of shadow and light.

Similarly to the shadows, it feels like more effort is put into the cinematography in some areas than in others. Camera angles during cutscenes and conversations are mostly static, likely because of the difficulty of combining a moving camera with stop motion animation. Static angles aren’t always a problem when they’re approached with creativity and diversity, and characters are captured from interesting and unexpected angles during key moments in the plot. It’s during the slower, more incidental moments that dominate most of my playtime where the cinematography disappoints. The camera cuts back and forth between the same few boring over-the-shoulder shots dozens of times while the characters converse. The visual tedium this creates can make prolonged playtime challenging for my attention span.

The more I play, the more I begin to recognize other imperfections in the visuals. When Harold climbs up and down stairs, his legs stretch and contort as though they have been digitally manipulated to keep them planted on each step. Sometimes when he enters large areas, it takes a moment for all of its visual assets to load in and I can briefly see the cold, white, untextured heads and limbs of non-player characters before their stop motion animated assets appear. It makes me wonder how much of Harold Halibut is truly animated by photographed puppets and how much of it is digital trickery.

I do not write this to accuse the developers of deception. Stop motion animation is already a monumental task for a ninety minute film feature. To attempt it in a videogame, containing hours of dialog and multiple huge environments, certain shortcuts are not only understandable, they are necessary. Yet these occasional lapses in technical performance impact my experience. It never stops being visually unique, but each time I get a glimpse at the magician setting up their trick behind the curtain, my acceptance of the illusion lessens.

It’s with the overall plot that my misgivings turn into disappointment. Reflecting his lowly position in the Fedora’s hierarchy, Harold has little agency. Few of his actions contribute meaningfully to the plot, including its incitement.

I am confronted with this fact right from the start. The first chapter begins as Harold is charged with completing his daily chores around the Lab District. With those tasks finished, Harold watches a televised presentation from the All Water Corporation revealing the launch of a communications buoy. He goes about his business for several more days, assisting the science crew with various research and power-generating chores. The next major event is Harold, along with the rest of the crew, overhearing a message the buoy receives from Earth which is accidentally broadcast over the Fedora’s intercom. The next day an embarrassed Brenna Casselchop admits that they did receive a message and apparently plays it for everyone, but it is clear she is hiding the full meaning of the message. This doesn’t concern Harold, who continues doing chores around the Fedora.

Little of the plot happens to Harold. Instead, the plot happens around him. Even as he is drawn more directly into its events when he is clandestinely recruited by the Lightkeepers and rescues an aquatic humanoid alien from the Fedora’s filtration system, the greater quantity of my playtime is focused on Harold awkwardly helping his crush establish a bakery, deliver mail from a dead letter office, and reuniting estranged quadruplet brothers. The story is meandering and unfocused, indulging in tangents and details that inform me about life on board the Fedora, but do not inform me about its current, urgent situation. It takes over ten hours of playtime of thirteen total for a clear conflict to appear.

I must ask the question: Why is Harold Halibut the protagonist of Harold Halibut? In this setting filled with fantastic science, corporate intrigue, idealistic rebellion, and interspecies diplomacy, why is the ship’s handyman through whose eyes I view these events? The story of how ordinary people are affected by extraordinary events beyond their control is even one I am interested in. Harold Halibut fails to make it interesting.

Harold seems unaffected by everything happening around him, along for the ride because his job on the Fedora is to be along for the ride, supporting much smarter, more independent, and more interesting characters. This makes the story’s conclusion, when Harold makes a choice that suggests he has been profoundly changed by everything he has experienced, challenging and ambiguous but for all the wrong reasons. I don’t ask, “Why did Harold do that?” because there are many possible answers. I ask because for the first time I am seeing Harold as more than a hangdogged errand boy. A single moment in the filter station when Harold sings to himself about there being more to life isn’t enough to create the depth of character the ending tries to capitalize upon.

If the plot is unbalanced, then the gameplay is askew. The vast majority of Harold Halibut’s interactivity is devoted to guiding Harold up and down the Fedora’s hallways and choosing different compartments from the tube transport network, which stripped of its science fiction functionality is essentially an elevator. Other interactive elements feel perfunctory, like deducing how to clean the Fedora’s filtration system, which is operated by pictographic buttons whose purpose only feels obvious in retrospect. I can play for hours before encountering another of these minimally interactive puzzles.

Narrative videogames are inherently dialog heavy, so it is common to add interactivity into conversations by letting the player choose what the character will say next. Harold Halibut has this feature, but utilizes it sparingly. An uncommon few conversations will let me choose a handful of Harold’s response. It can be a long time and many conversations later before I encounter another exchange that isn’t completely scripted.

When I am given a choice of what Harold will say next, the dialog prompts are deceptive. The prompt I select from the bottom of the screen rarely resembles the words that actually come out of Harold’s mouth. Some prompts are also timed, like when Harold walks in on a boy being questioned by the Fedora’s security officer. I have just a few seconds to read multiple wordy text prompts, choose one which then doesn’t represent what Harold says next, and to cap it off the choice doesn’t seem to matter anyway. No matter what option I select in any conversation, the plot continues in the same way as before. Prompts feel pointless, existing because narrative videogames are expected to have them.

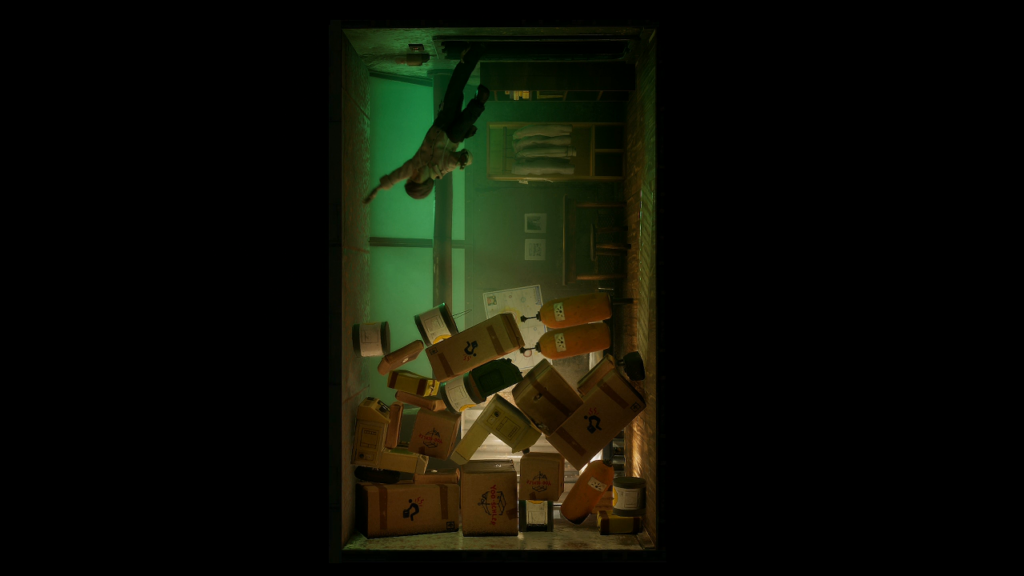

There are times when I feel like Harold Halibut is aware of its interactive deficiencies. One of Harold’s more obnoxious labors is clearing out a storage room, which involves picking up and carrying boxes, one box at a time, between three different rooms. Just when this task becomes laughable in its repetitiveness, suddenly the perspective changes. I see a room turned on its side, and boxes begin to rain down through the doorway and I can drop them to the bottom of the screen like tetrominoes in a puzzle videogame. As the room overflows with boxes, Harold himself appears at the top of the room, dangling from his ankle like a toy caught in the claw of a crane game. The sequence ends when Harold plummets into the pile of boxes and is never spoken of again.

For about ninety seconds, Harold Halibut seems to become fed up by its own drudgery and throws this inexplicable bit of whimsy at me. If it did this more often, I might have felt less bored by its lack of interactivity.

The exception to all of my complaints is Chapter 5. It sends the protagonist through a psychedelic dreamscape at breathless speed. Harold runs up an endless hallway while his sneering crewmates parade between adjacent doors, Scooby Doo-style. I control Harold’s breaths, in and out, each breath summoning a different vision of his friends. Joined hand-in-hand with a fish alien, Harold flies after a massive jellyfish through a shadowy solar system, gathering up the rings of stars it leaves in its wake. Every moment is visually breathtaking and every moment capitalizes on its simple interactive elements to maximum effect.

If one hears “stop motion animated videogame” and imagines “Coraline: The Videogame,” Chapter 5 is as close as Harold Halibut comes to fulfilling that hope. It’s barely a half-hour long and most of its best moments appear in the trailers. It’s a microcosm of this videogame’s potential and its reality, of the incredible devotion its creators must have put into its stop motion animation and the limitations that method imposes upon the final product.

Harold Halibut’s use of stop motion animation to create its world and characters is an impressive technical feat. Once that novelty wears off what’s left is a lumbering plot and intermittent set pieces that only gesture at interactivity. Most of my time playing consists of thirteen interminable hours watching Harold trudge up and down hallways and having long conversations with his crewmates, most of them not related to the ongoing plot. Prospective players may get the best out of Harold Halibut by watching any of its trailers on YouTube instead of playing it. It’s a wonderful idea for a videogame and I wish I enjoyed it more than I did.