The Bookwalker: Thief of Tales is a narratively-driven adventure videogame set in a world where writers can dive into books and interact with their settings as though they are real and alive. I play as Etienne Quist, a novelist who begins the story sentenced to thirty years of labor for a mysterious crime. Part of his punishment includes shackles on his arms which inflict “writer’s block,” an affliction that drains his lifeforce every time he tries to change or add to a story.

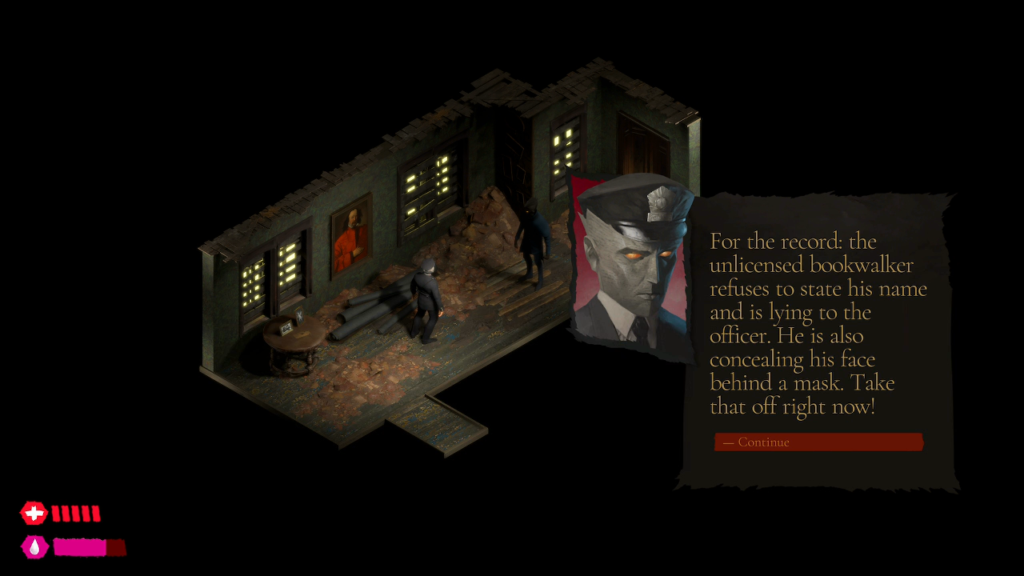

Etienne is contacted by a man who promises to remove the shackles early if Etienne will do some work for him: Bookwalk into another writer’s story, pilfer a MacGuffin from its narrative, and deliver it to the man’s organization in the real world. Objects stolen in this manner are reworked into other stories and published under a different author’s name. This thievery is a kind of plagiarism and is illegal in Etienne’s world; if he’s caught by the Writers’ Police in another author’s story, he will be in even more trouble. I guide Etienne through six heists, along the way learning more about the illicit organization he works for and the unusual crime he committed that led to his harsh sentence.

The Bookwalker’s greatest attribute is undoubtedly its plot and setting. Bookwalking, a writer’s ability to enter a story and manipulate it literally from the inside out, is an incredible imagining of the creative process that suits a videogame format well. Every other detail about the narrative and setting grows from the implications of this power: the consequences both from bringing objects into the narrative and removing them; the ethical concerns of Bookwalking into a story that is not your own; the institutions that would mandate legality and bring justice to these actions; and the criminal underworld that would seek to exploit them. The Bookwalker has one of the most exciting and original settings I’ve encountered in a videogame in years.

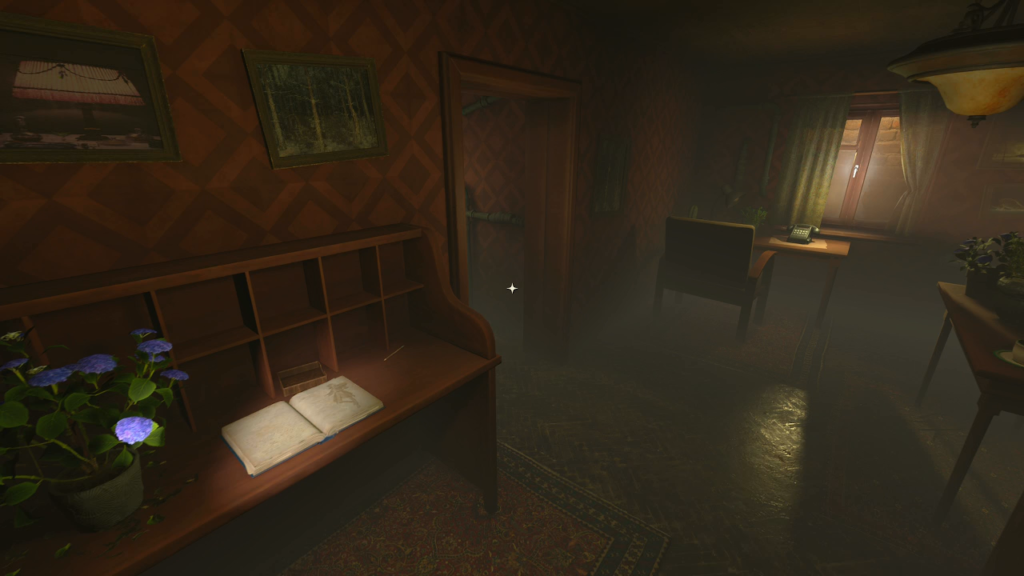

Each heist begins with Etienne answering a knock at his apartment door to find a suitcase left on his doorstep. Each suitcase contains a few objects that act as a kind of dossier of his mission: A cutting of a review for the book, a photograph of the book’s author, a description of the object Etienne must steal, and a copy of the book itself. A handle beneath a gauge opens a sealed vault where the stolen object is placed; it only opens with a grinding of invisible gears and a burst of steam, suggesting that the seemingly-ordinary suitcase is a mechanical marvel. It makes me wonder just who Etienne’s illicit employer really is and where they get their resources.

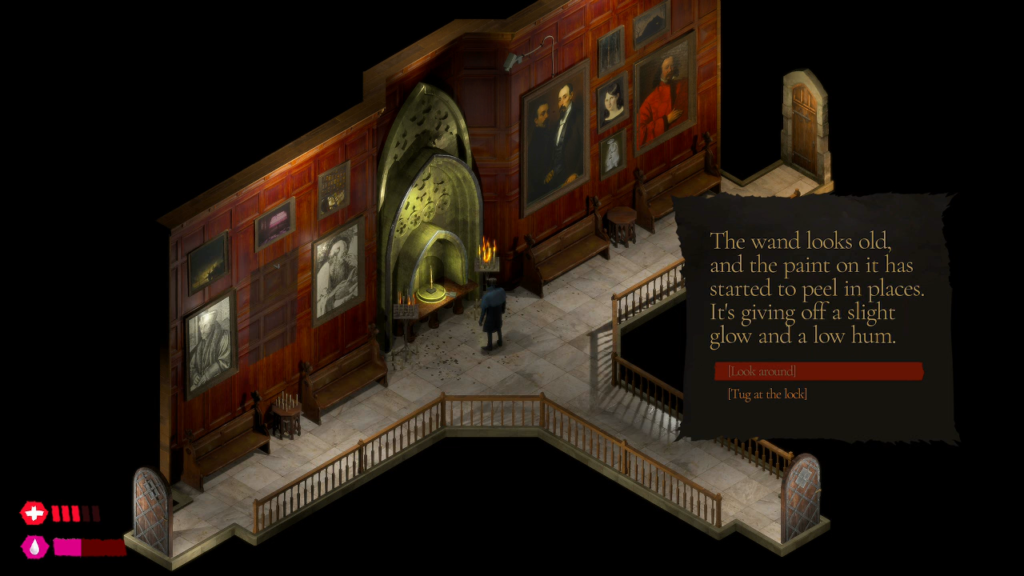

The six books Etienne enters are diverse in their settings and themes, though most have at least a subtle bias towards science fiction. Settings include a medieval dungeon that imprisons an immortal alchemist, an urban fantasy where a school for magic tries to teach young wizards and witches computer programming, and a desert punk apocalypse where everyone lives on trains and trades using a bizarre sand-based economy.

Each of these settings contains an iconic MacGuffin which Etienne must steal and return to the world where it is delivered to his mysterious employer. Some of these objects are recognizable fictional artifacts like Thor’s hammer and the sword Excalibur, still locked in its stone. I interpret the presence of these familiar objects as a sign that, in The Bookwalker’s world, writers have been stealing objects from their peers’ books for a long time, passing them from story to story for so long that their origins have been muddied and forgotten.

The story isn’t without at least one weakness. Early in his first mission, Etienne encounters the corpse of another Bookwalker who carries a character extracted from a story. This character, who remembers little of his identity and exists only as a voice in a copper lantern, is dubbed Roderick by Etienne and acts as his assistant during the heists. Roderick recalls fragments of his past as the story goes on, enough for me to correctly deduce his identity on the first try. He is, strangely, the only character in The Bookwalker to not be a wholly original creation. He is taken from a story in the public domain.

Roderick’s true identity adds nothing to the plot. The last second plot twist reveals nothing new about his relationship with Etienne or his situation at the story’s beginning. He exists as a recognizable reference from famous literature and nothing more. He functions more as a fairy companion, present to provide Etienne with clues and reminders about his current goals and give him someone to talk to on what would otherwise be a very quiet and solitary adventure. This makes the epilogue, which focuses on Etienne and Roderick’s relationship, feel bereft of emotion or closure. Roderick is back where he belongs and it means nothing to the narrative or to me.

Visually, The Bookwalker is just as creative as its concept. I am first drawn to play by the visual design of Etienne’s head. It appears as an opened book with his face printed on the covers and spine, while the unfurled pages behind him are stylized to resemble an unkempt haircut. It’s such a striking image that I am disappointed to learn late in the story that it is a mask and not the glamour that all writers adopt while Bookwalking. The mask is meant to hide Etienne’s identity while he performs his thefts, but it causes so many problems with each book’s characters that it seems to invite more trouble than it prevents.

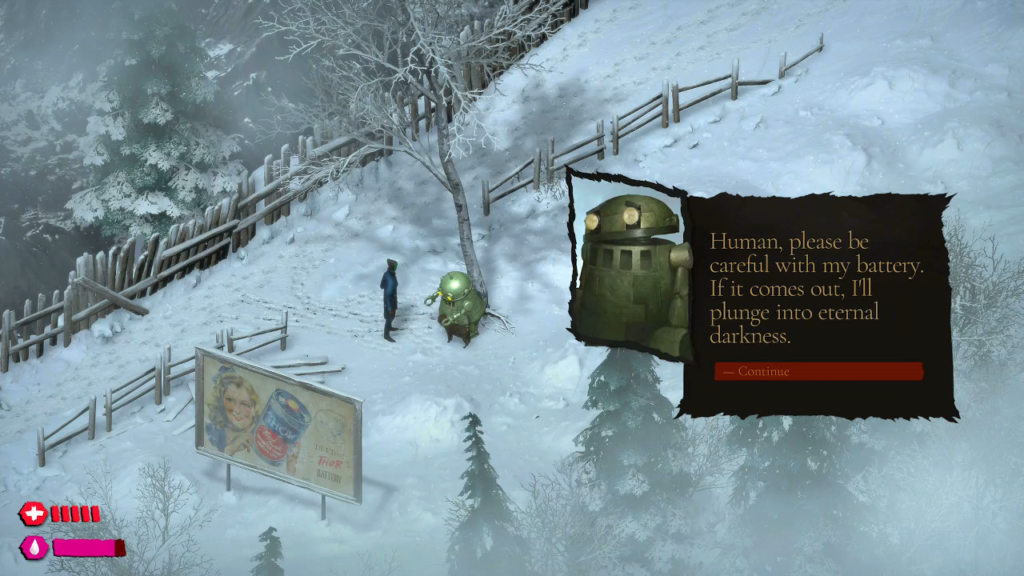

The best visual idea is how the different worlds are portrayed. Etienne Bookwalks into a story through a swirling vortex of words printed on browning paper. Once inside a story, I view the environments from an isometric third-person perspective. This grants me sight of all spaces around Etienne and lets me guide him effortlessly to objects of interest in each room. It essentially grants me the ludic equivalent of third-person limited omniscience.

The real world of Etienne’s apartment is played in first-person. To find all the details hidden around his apartment, particularly reading the letters shoved through a mail slot that provide a glimpse at Etienne’s ongoing financial problems, I must carefully point the player character’s vision into every corner. Instead of the omniscience granted from viewing a story from a detached, almost neutral perspective, time spent in Etienne’s apartment puts me behind his eyes and inside his narrow perspective.

During the segments in Etienne’s apartment, all of its non-player characters are hidden. His neighbors exist as disembodied voices speaking through cracks in doors. When a courier picks up stolen artifacts, only their arms and legs are visible. I imagine this was a practical choice to hide how low detail the character models are, a factor that is concealed better in the zoomed out Bookwalking sequences, but it has the additional effect of making the protagonist feel lonely and isolated. Bookwalking back into a story, while legally and ethically dark, feels much less suffocating than the narrow rooms and suspicious neighbors in Etienne’s tiny, lawful apartment building.

Its actual adventure videogame mechanics is where The Bookwalker is weakest. Despite the variety of settings, Etienne uses the same few tools in most of his missions. Locked doors are opened with a lockpick. Containers are forced open with a crowbar. Delicate objects are manipulated with pliers. Most of Etienne’s heists consist of searching every box and drawer for the scrap parts needed to craft these core tools at one of many crafting tables found across every environment. Once all three are in his possession, he encounters few obstacles he lacks the tools to overcome.

Each book does contain a few objects unique to their settings. At a manufacturing plant filled with sentient robots, Etienne must swap around a limited number of batteries to activate different machines. This includes some of the robots, which the narrative does its utmost to make me feel horrible when Etienne essentially rips out their modular hearts. The desert punk story does the most work to distance itself from Etienne’s core toolset, tasking him with scrounging up enough bags of special sand to buy his way into a protected city. This requires him to trade away almost everything in his pockets and potentially perform a few more unsavory actions.

The most intriguing puzzles require Etienne to take advantage of his ability to carry objects with him into books. This is demonstrated immediately on his first heist when he Bookwalks straight into a prison cell. To pick the cell’s lock, he must carry a lockpick from his apartment into the book. Almost every subsequent heist has a similar puzzle, most of them forcing Etienne to bother his neighbors for a shovel or a pickaxe as though he is borrowing a cup of sugar, to their growing bewilderment and annoyance. It’s a fun idea for a puzzle, but it never expands beyond this. At some point during each heist, Etienne encounters an obstacle the setting provides no solutions for. Roderick suggests Etienne retrieve something from his apartment building, he does so, and the problem is solved with little fuss.

When there are no tools available to solve the current problem, Etienne can make use of his writer’s powers. The shackles on his arms make this a taxing and risky choice, but there are multiple puzzles that can be solved or bypassed by having Etienne write a new solution into the story. This drains his limited Ink reserves, but he can recover them by gathering garbage and scraps found in nearly every room and crafting them into a bottle of ink.

Etienne’s ability to manipulate the narrative in this way is a dangerous addition. It’s a deus ex machina, potentially trivializing any problem he encounters at the cost of some ink. It also stands in opposition to one of the first things I am told at the story’s beginning, that Etienne’s shackles prevent him from changing or adding to a story without great pain and effort. Apparently these difficulties can be overcome by drinking a bottle of ink. Regardless, it’s a fascinating ability I wish was explored more than the few times Etienne is prompted to explore it during his criminal Bookwalks.

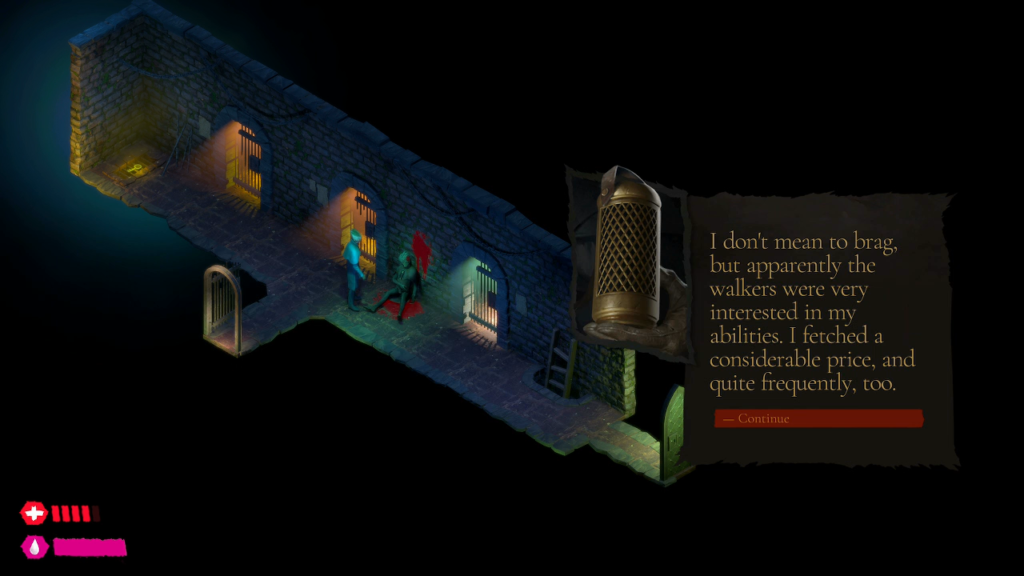

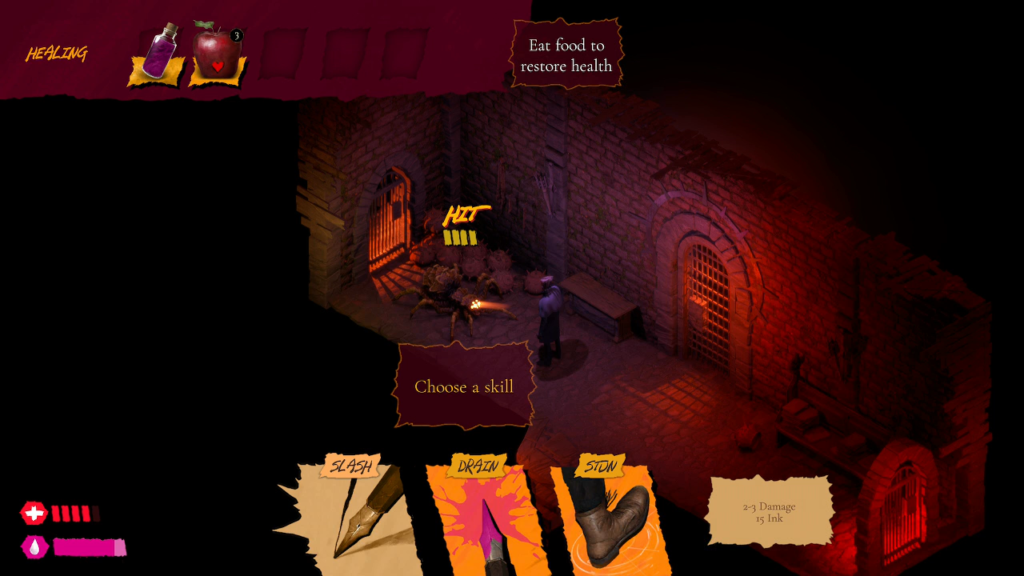

Midway through Etienne’s first heist, he is ambushed by a spider called an “Ink Eater.” These insects are not part of the story, but invade its interiors much like the Bookwalkers and attack any people or characters they come across. This encounter is where I am bewildered to discover The Bookwalker has a rudimentary turn-based combat system inspired by traditional RPGs.

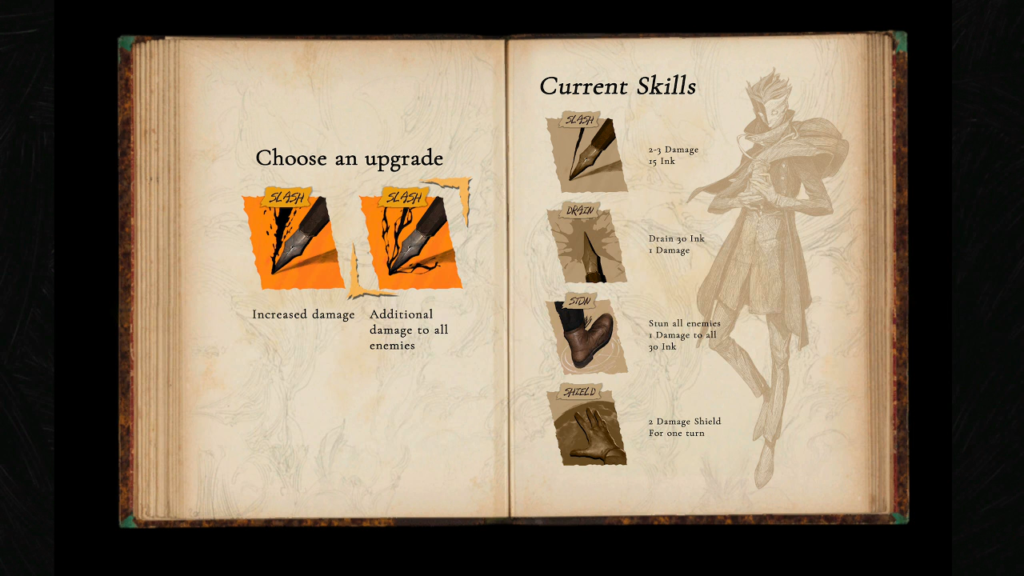

Etienne has four abilities he may use in combat. Two are powered by Ink; he can Slash with his pen to deal a decent amount of damage, or Stun the entire enemy group with a kick, delaying their action for a single turn. If Etienne runs out of Ink, then he can Drain a single enemy, which deals a small amount of damage and restores a large amount of Etienne’s Ink pool. His final ability is a Shield that blocks a few points of incoming damage.

This combat system is not deep and some of its skills are of dubious use. The action each enemy is about to perform appears above their head before turns are executed, giving Etienne a chance to respond strategically. An enemy who is Idle that turn can be ignored. An enemy who is about to Hit Etienne for a single health point may be dispatched with a Slash attack. A Strong Hit will take two of Etienne’s limited hit points. Stun sounds useful in this situation, but it only delays enemy actions for a single turn and does not change the actions they will perform. It essentially deals a single hit point of damage at high ink cost but otherwise does not change the outcome of the turn; two Slashes in a row are nearly always a better option than a single Stun and a Slash.

The combat system’s inanity is made up for by being easy. The enemies Etienne confronts, whether as Ink Eaters, hostile characters, or other forces invading the story, miss their attacks frequently. Resources to restore Etienne’s health and ink pools are plentiful if he opens every container in every room and may be used in combat without using up Etienne’s combat turn. After every Heist, Etienne may upgrade one of his combat skills at a ledger in his apartment. Improving the strength of his Slash and Shield turns the encounters from easy to trivial.

The Bookwalker’s combat systems are simple and easy, and not in a good way. They are padding, existing to create an illusion that the videogame is longer and more action-packed than it is. It would immediately be improved if they were removed and replaced with puzzles more suited to the adventure game format.

The best ideas in The Bookwalker: Thief of Tales are in its setting and its visuals. As an actual adventure videogame, concerned with exploring an environment, discovering the features within it that are broken, and finding the pieces needed to put them back together, it is rudimentary. It recycles many of the same ideas across its many environments, creating the practical but uninteresting suggestion that a crowbar or a lockpick is equally useful in an alchemist’s torture dungeon as in an urban school for magic. Even its narrative isn’t as interesting as the setting it takes place in; the revelation about the crime Etienne committed, the nature of the organization he works for, and the true identity of Roderick ends up being either predictable or explored in such little detail that they cannot be compelling. It’s a good thing the setting and the visuals are so striking, as they’re the only things that really keep me engaged throughout all of Etienne’s heists.