Ebenezer and the Invisible World is a non-linear platformer based on characters from Charles Dickens’ 1843 novella A Christmas Carol. Yes, this is a real videogame. A Christmas Carol tells the story of Ebenezer Scrooge, a wealthy and miserly moneylender, who is visited by the ghost of his business partner Jacob Marley and three Christmas Spirits. Confronting him with visions of his past, present, and future, they inspire Ebenezer to use his wealth and influence to improve the difficult lives of the impoverished people around him in Victorian London.

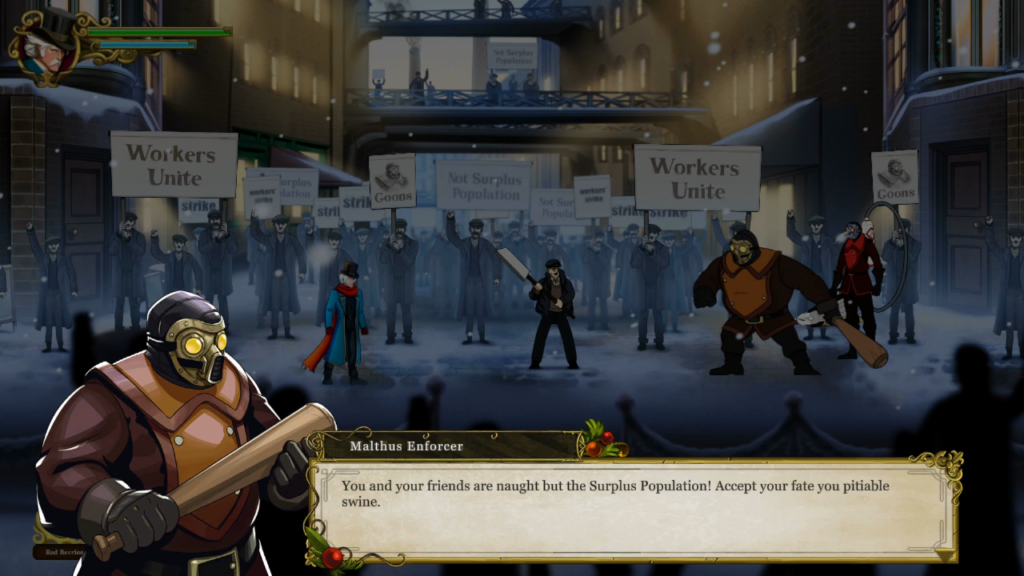

Ebenezer and the Invisible World picks up a few years after those events. The Christmas Spirits have continued their holiday task with Caspar Malthus, a contemporary of Ebenezer’s, showing him a future where he forsakes his family, friends, and business, all to create a device that generates limitless power. Just when he succeeds with his creation, he dies, and the device shatters before anyone can benefit from its use. This time the Christmas Spirits’ benevolent haunting backfires. Instead of being humbled by the experience, Caspar is inspired by a fourth, malevolent spirit to use the visions to create the power source in his present day. Now wielding endless energy in Victorian London, Caspar becomes a bitter autocrat who lays off his entire factory workforce and oppresses and abuses them with a private police force when they protest.

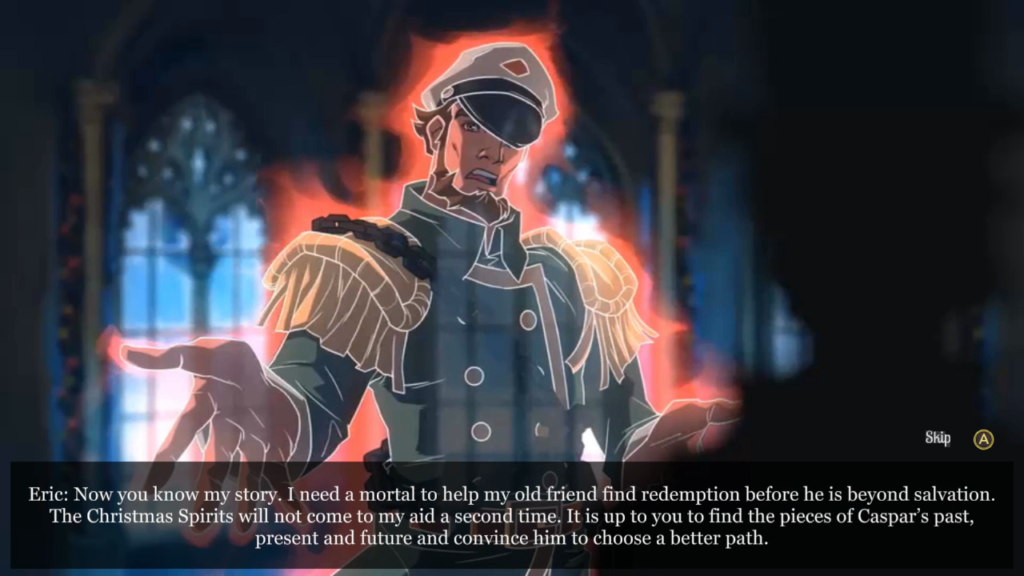

On Christmas Eve a year later, Ebenezer is approached by the ghost of Eric Fellows, Caspar’s equivalent to Jacob Marley. The Christmas Spirits refuse to offer Eric any further aid following the debacle so in desperation he recruits Ebenezer, whose experiences have left him with the ability to see and interact with the deceased who still wander London: The Invisible World. It falls to the elderly moneylender to platform across an open-ended, side-scrolling London, enlist a strange collection of ghosts with incredible powers, and deliver Caspar improvised warnings from his past, present, and future that might save his soul from the mysterious fourth spirit.

Ebenezer handles like a typical platforming protagonist at his adventure’s outset, able to run and jump through a London strewn with ramps, platforms, and rooftops that seem more like a videogame playground than an industrial age cityscape. A few exchanges between friendly characters highlight the unlikelihood of Ebenezer, a man well past middle age who has lived his life concerned with business and profit, performing these acrobatic feats with tireless skill. Part of The Invisible World’s charm is it knows how audacious its premise is. It leans fully and unquestioningly into its own absurdity, offering the whimsical explanation of “a Spirit did it” if ever Ebenezer’s aptitude begins to stretch credulity.

This spiritual aid comes in forms familiar in non-linear platforming, yet not wholly predictable. Ebenezer does learn to double jump, but surprisingly late in the adventure. Before then, Ebenezer must make due with bouncing off the tops of spectral balloons that appear across London. He can also dash through the air, temporarily becoming intangible along the way so he may pass through some obstacles. The most original traversal idea comes in the form of special mirrors. By entering them, Ebenezer can platform through cloudy obstacle courses suspended in an endless void of purple clouds and ruined aqueducts, emerging from them through another mirror nearby.

When Ebenezer first ventures from his manor—now filled with happy servants and lavish Christmas decorations to highlight his transformation into a munificent philanthropist—he encounters Caspar’s police force. Equipped with impenetrable shields, electrified blunt weapons, and gas-spewing contraptions, they don’t fit in with the merrily lit streets of Victorian London at Christmastime. They look more like the fascist stormtroopers England shouldn’t have to deal with for another hundred years. Caspar’s private police recur across Ebenezer’s adventure, but I soon find they are not nearly his most numerous foes.

London teems with residents of the Invisible World, the unrepentant spirits. Each of them has a name and a history logged in the journal-like menu, telling me exactly how they ended up as a bitter and hostile ghost impeding Ebenezer’s quest. Lady Adeline was a tactless critic in life; in death, she hurls phantom tomatoes to express her opinions. Wailing Wendy would be an ordinary banshee in any other videogame, teleporting across the screen before screaming up a beam of damaging sonic energy. Here, I learn that she was in love with her best friend who did not return her affection. Her damaging wails are her pent up grief as without the love of her friend she refused to love herself.

The unrepentant spirits’ visual designs are just as detailed as their backstories, drawing from elements explained in the novella. In A Christmas Carol, Jacob Marley appears before Ebenezer wrapped in a heavy chain, explaining that it is “the chain I forged in life.” Each link represents one of his cruelties to his fellow man and he is doomed to wear it for eternity. The character designs of the unrepentant spirits in The Invisible World reflect this detail; chains feature prominently in most of their designs. Titus, a belligerent bully to all around him, has become so wrapped up in his chain he can no longer stand and so shuffles on his bottom to reach Ebenezer and belch up toxic gas. Evelyn Michaels was a vain tightrope walker who resented sharing the spotlight. Her ghost now balances high in the air on the chain she forged and pokes at Ebenezer with her balancing stick to attack.

Ebenezer fights off his enemies with what one weapon description calls his “mastery of tactical cane combat.” His cane attacks quickly but has limited range. To make up for this, with a simple button press he performs a quick dash backwards to avoid an enemy’s counterattack. Ebenezer begins with only the Regal Redwood, an ordinary cane, but with thorough exploration of the world he uncovers additional canes with effects like a wider swing radius or a weak projectile.

More interesting additions to his arsenal are the Spirit weapons. These metaphysical weapons come in varieties like an axe, which has a slow swing but great attack power, and chains, which have a narrow field of effect but great reach. It’s easy to swap quickly between any of Ebenezer’s weapons in a menu, letting him use different weapons which have varying utilities against certain enemies.

It’s tempting to use Ebenezer’s Spirit weapons thanks to their greater range and strength, but they have an important caveat: They do not refill Ebenezer’s Spirit energy. Only his canes have this power. Spirit energy is used to wield Ebenezer’s most destructive abilities, each of them actually unleashed by a cadre of friendly ghosts that follow him throughout his adventure.

Each ghost has a radically different function to their powers, making them more or less useful depending on the area’s geography. Bruce Hagan was imprisoned for his prejudices before his death; as one of Ebenezer’s attacking spirits, he uses the ball and chain still shackled to his legs as a mighty flail, dealing damage with a single colossal blow. Gaetano Lo Grosso, a lamplighter, is Bruce’s practical counterpart, spinning his long candlestick in a small area to deal large amounts of damage through many small hits.

The choice between Canes and Spirit Weapons creates an interesting choice in playstyle. Wielding Spirit Weapons, Ebenezer is a more traditional platforming fighter, dealing good amounts of damage from different ranges and angles. Wielding Canes, he functions more like a wizard. Canes are less versatile as damage dealing weapons and their inferior range puts Ebenezer in much more physical danger, but the regeneration they confer to his Spirit energy lets him use his allies’ powerful abilities in combat more often.

Unlike the hostile spirits who impede Ebenezer’s journey, the ones who join him are repentant. Like Jacob Marley and Eric Fellows, they regret their actions in life and seek to heal some of the damage they caused. Ebenezer encounters them almost everywhere in London whereupon they explain their troubles. In order to enlist their aid, Ebenezer must first help them to right their wrongs through completing a sidequest. Objectives are straightforward and predictable, tasking Ebenezer with defeating a powerful enemy or delivering an item to another character somewhere in London.

The difficulty in completing these sidequests is their objectives are not marked on the map and the conditions needed to complete them are not always clear. To add Luscinia Saari to Ebenezer’s party of spirits, she wants him to deliver one of her beautiful dresses to a poor girl who has been wandering London gazing longingly into shop windows. Getting the dress is straightforward—there is only one actual shop in the entire game world—but to find the girl to whom the dress must be delivered, Ebenezer wanders many broad areas talking to every non-player character until he finds the right one. There’s a similar dilemma involving Angus Bouchard, a fisherman who wants Ebenezer to drive his former criminal business partners out of a fish market. Where this fish market is located is not clearly communicated.

These vague directions give a sense of aimlessness towards completing the repentant spirits’ various tasks. Ebenezer must spend an inordinate amount of time wandering back and forth across screens he’s already visited, talking to people he’s already met, looking for the right person who will complete the quest. It quickly becomes tedious.

It’s not just the repentant spirits’ objectives that are unmarked, but every quest and collectible. Whenever Ebenezer enters a new screen, its entire perimeter is automatically logged on his map whether he explores it thoroughly or not. If there are any hidden treasures beyond an obstacle Ebenezer lacks the power to bypass, the map does nothing to help me remember he should return to that space later. The only way to know is to remember myself. This isn’t unheard of in a non-linear platformer, but it does feel notably archaic in a genre that has become much more friendly about marking collectibles in the past decade.

When Ebenezer is able to reach a collectible, they aren’t always rewarding. A handful are new weapons. Many are Heirlooms, equippable items with magical properties that change how Ebenezer moves or attacks. Most hidden collectibles are treasure chests or vaults that Ebenezer opens by beating on them with his cane. They contain randomized reagents that are delivered to a pair of alchemists in western London who can increase Ebenezer’s health and spirit totals.

I’m disappointed to see The Invisible World follow this route for upgrading the player character. In a non-linear platformer, finding a collectible should always provide a discernible and immediate reward. When random items are turned in to a non-player character instead, it delays the reward and turns it into a grind. Ebenezer scours London for every chest and vault and even then may come up short on ingredients to increase his health and spirit totals. The only choice to find the needed ingredients is to grind them from defeated enemies. Again I feel that The Invisible World becomes tedious.

All of this I have described could add up to an adequate and unremarkable addition to the smorgasbord of indie non-linear platforming. What truly troubles Ebenezer and the Invisible World is an overall lack of polish. Everywhere Ebenezer travels in London, I witness minor problems.

Character interactions are marked by occasional conversation boxes that are blank or attribute dialog to the wrong character. Ebenezer helps a spirit named Haley Hall; when she adds her powers to Ebenezer’s collection, the confirmation box refers to her as “Rose Reed,” a different spirit he will not encounter for many more hours. When Ebenezer crosses from the Observatory to the Malthus Factory by aerial cable car, the camera pulls so far out that I can see the sudden edge of the beautifully painted London skybox and into the empty blackness beyond it. The Apothecaries who expand Ebenezer’s Health and Spirit totals only respond to the Jump button; every other NPC responds to the Confirm button. Sidequests sometimes list incorrect objectives. After I have completed all of Ebenezer’s main quests and finished the story, when I reload the file I am no longer able to browse his unfinished side quests.

And on and on and on, each minor problem becoming another unbreakable chain that binds itself to the Invisible World. By the time I see the ending, my experience is weighted by grievous disappointment.

The best thing about Ebenezer and the Invisible World is its premise. A sequel to A Christmas Carol isn’t the most outlandish idea, and following The Invisible World’s plot points I could easily imagine it being a dialog-driven adventure with simple puzzles. Instead, its developers made the unusual choice to make a non-linear platformer. Where it runs into trouble is its interesting choices stop there. The conventions of non-linear platformers are familiar by now and The Invisible World does little to stray from its comfortable box. A rudimentary map makes collectibles difficult to obtain. When Ebenezer does find them, they don’t feel especially rewarding, either through minor or delayed effect. An overall lack of polish to design and text serves as further obstacle to full enjoyment. I hoped Ebenezer and the Invisible World would be a new classic holiday videogame. Instead it is a footnote.