Flipping Death is a story-driven puzzle videogame about the sordid inhabitants of Flatwood Peaks, a ghastly town with a grisly past and a bloody present. The night is Halloween and I play as Penny Doewood, a young woman who has just been fired from her job at a funeral home for getting way too enthusiastic about her devil costume in front of a customer. Running off with her boyfriend to enjoy what remains of the holiday, she ends up in a local mausoleum and falls through a rotten floorboard onto a jagged rock. Penny awakens in a dark mirror image of Flatwood Peaks and soon meets Death, who mistakes her costume’s devil horns for the real deal, assumes she is his long-awaited temp, and pushes his scythe and cloak on her before disappearing on vacation.

Deciding to go with the situation for now, Penny assumes Death’s duties, helping Flatwood Peaks’ recently and not-so-recently deceased resolve their unfinished business in the living world so they can pass on to the afterlife. The situation is made more complicated when Penny discovers someone or something has taken control of her former body and seeks out the bones of a centuries-old murder victim with apparent ill intent. Penny must juggle her new duties as Death’s temp with investigating the theft of her body in the hopes that she might get to live again.

I progress through Flipping Death’s seven levels by helping Penny possess Flatwood Peaks’ living inhabitants. Each of their unique abilities solve puzzles which work towards the completion of a checklist tracking each ghost’s unfinished business. It’s not always clear how freeing the skeletons of a knight and his squire from the blowhole of a battle-scarred whale will lead to waking a thrill-seeking biker from her coma, but everything always links together in a ludicrous yet linear logic. Every level applies thick layers of slapstick to dark topics so I’m spending too much time being amused to be horrified. Taken as a whole, Flipping Death feels like an Addams Family comic coming to digital life.

Flipping Death’s presentation is intrinsic to its charm and design. Flatwood Peaks’ inhabitants are paper thin, tall, and possess disturbing proportions, as though a recognizable human body has been taken then stretched almost until it snaps. If the world were slightly more cartoonish, the wheezing of an accordion would not sound out of place accompanying their movement. Characters’ upper heads are disconnected at their jaws, so the top halves of their skulls flop up and down as they speak. With pallid orange skin and dark circles under their eyes, every character has a monstrous edge to their design. This effectively blurs the lines between the living and the dead; the friendly ghosts Penny encounters seem even less threatening when the living look just as unsettling.

Despite their visual similarities, the living and the dead are carefully segregated into separate-but-identical halves of Flatwood Peaks. When Penny possesses a character, her transition from the living half to the deathly half is represented by the world flipping over itself like I am turning the lonely, single page of a morosely colored picture book. This has the side effect of the town’s halves mirroring themselves. Most of my navigation problems result from left in the living half becoming right in the deathly half. This proves surprisingly difficult to keep straight in my head, but the low stakes—Penny cannot die, let alone fail any of her missions—makes my confusion only a brief setback.

Flatwood Peaks is typified by towering hills neighboring plunging valleys. It’s common to take two steps out of a building and fall dozens of feet to a valley far below. In keeping with the slapstick humor, this causes no harm to even the living characters—though I have to consciously prevent myself from comparing their invincibility to Penny’s fate in the prologue. Residents of the living half reach their precarious houses and businesses using a Seussian network of elevators that twist and bend across the landscape in every direction. For longer distances, characters can take a car across town, winding along a suspended roadway rich with dizzy curves while a horn chortles a bluesy tune. The deathly half is less mechanically advanced and Penny must travel by foot, jumping up and down platforms to reach high and low locations. Flipping Death’s platforming elements are light and should prove little obstacle to even the most inexperienced or uncoordinated player, but they do exist.

The strongest contrast between Flatwood Peaks’ two halves is created through their use of color. The living half is bright and warm, its trees and bushes resplendent in russet autumn colors. Its buildings stand out against the landscape in vibrant shades of golds, reds, and greens. The deathly half generates an eerie aura using ghostly blues and sickly purples. It’s an obvious choice for the land of the dead, but these colors are cliches because they work so well. To give the deathly half some more action, some elements of the living half reveal themselves to be otherworldly creatures when the world flips around. Ordinary objects like gumball machines and even entire buildings grow eyes and teeth. Some even sprout legs and chase Penny across the landscape. Compelling objects to move in this way is key to solving several puzzles.

As Penny platforms across the world, she comes across its living inhabitants as silhouettes with glowing purple auras. They must be possessed to solve puzzles, but before this can happen Penny must remove a lock on their body that demands a certain number of the krill-like spirits that flit around Flatwood Peaks’ deathly half.

Most spirits are grabbed automatically as Penny passes by them. Others are found in specific locations and are claimed by overcoming simple platforming challenges. At no point are these spirits’ existence or their necessity for unlocking a living character’s body explained. They are part of the design as an extraneous mechanic to make the short length last that tiny bit longer. I find them immediately tedious and always roll my eyes when a character needed to solve a puzzle is locked behind just a few more spirits than Penny is carrying.

These possessable characters are outrageous and distinct. Tina is a hyperactive girl with piranha-like snapping jaws outfitted with disturbingly large braces. Pokeman is a small-time supervillain in a purple spandex costume who uses his telescoping arm to annoy people by poking them. Pokeman’s reign of terror is challenged by Ronald, the local police officer who is too bashful to exercise his authority. When Ronald falls asleep, he sleepwalks and becomes Cyril Berspace, a master criminal hacker.

Much of Flipping Death’s humor is derived from the characters’ dialog. They are loud and chatty, each and every word passing through their lips performed by a rowdy band of talented voice actors. They engage in incidental conversations with nearby characters when they are left alone, or sometimes with themselves if nobody else is around. These conversations are also useful for helping me identify who waits on the flipside before Penny can possess them.

Once Penny possesses a living character, Penny is able to speak to them from within their minds. Different characters have different reactions. Tina recognizes Penny as another person and happily chats with a new friend’s voice in her head. Pokeman dismisses Penny as unwanted thoughts trying to dissuade him from poking things. Ronald assumes Penny is his inner confidence finally asserting itself. It all skirts the line between absurdism and psychopathy, keeping with Flipping Death’s double-edged sense of humor.

Penny’s skill at mobilizing the living people she possesses is limited. This is understandable; it’s her first day on the job. They lurch in the direction I point the joystick as though compelled by a force pushing from within their chest, their arms flailing behind them like windsocks in the breeze. This maneuver is referred to as “quirking around.” Despite the odd animations that result from quirking around, moving possessed characters through Flatwood Peaks isn’t all that different from moving the player character in a platformer.

Each character’s unique talents are conveniently suited for solving puzzles that lead to resolving a ghost’s unfinished business. Tina’s snapping jaws are perfect for chewing bubblegum and blowing bubbles. Pokeman’s prowess at poking is useful not only for poking other characters, but also for reaching out-of-the-way switches and levers. Ronald’s shiny police badge can open doors that remain shut to others. Some characters appear in only one level. Others recur in many or most of them. Some are placed in a level as a red herring, their abilities never utilized to solve a puzzle. I spend time with all of them, getting to know their zany personalities well.

The worst part of any puzzle videogame is when I can’t discern its unique logical flow and I’m left plugging every character’s abilities into every available outlet hoping something new might happen. This desperate process often leads to hours of frustrated tedium. Flipping Death efficiently sidesteps this problem with its Hints system.

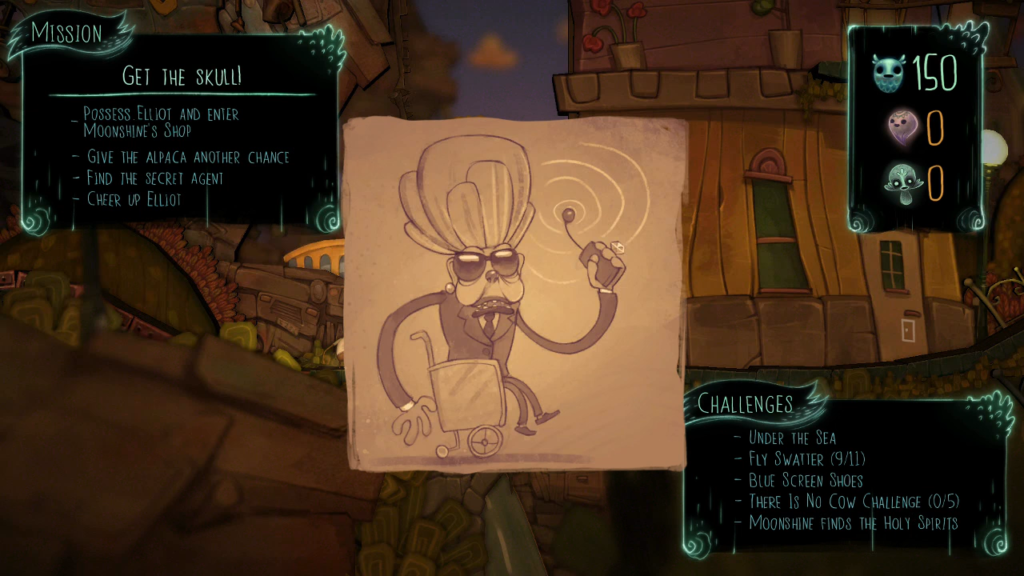

If at any point I’m stuck on what Penny needs to do next, I can open the Hints screen from the pause menu. A Hint shows me a simple picture demonstrating what needs to be done next for the story to continue. If I like, I can even follow these Hints step-by-step through every level, permitting myself to ignore solving puzzles and focus on enjoying the humorous visuals and performances. Thanks to Hints, I’m never left stuck on what to do next for long, keeping Flipping Death to a short 6 to 8 hour length.

Aside from Hints guiding me to puzzle solutions, each level is also outfitted with a number of Challenges. These puzzles are esoteric, requiring me to deduce their meaning from a single phrase like “Get Off My Lawn,” “Ice Cold Killer,” and “Blue Screen Shoes,” then guide the right character to the right place to use their skill in an unexpected way. Unlike main story goals, I receive no more clues for completing Challenges than their simple prompting phrases.

Challenges are completely optional. Completing them earns digital cards that give every character, living and dead, a complete name and history. If the platform supports it, some also reward achievements. I’m grateful these are all optional perks, as completing challenges can be obnoxious. A few can only be earned before certain core puzzles are completed. There is nothing indicating this is the case, requiring an entire level to be started from the beginning to attempt the challenge again if I inadvertently complete the wrong puzzle. There’s also an unintuitive challenge involving time travel which requires hopping back and forth between completed levels. I doubt many solve this one without a guide.

Flipping Death is a great choice for someone looking for a spooky videogame but isn’t enthused by most horror videogames’ penchant for gratuitous gore and lazy jumpscares. Flatwood Peaks is an interesting environment to explore, the kind of place Dr. Seuss might imagine in his nightmares. Its residents do a fine job keeping me entertained with their bizarre senses of humor and unlikely physical abilities. The puzzles are smart and do a good job enhancing the humor with their absurdity, and a generous Hint system keeps me from getting stuck on even the most outlandish leap of logic. Only the optional challenges potentially offer moments of frustration. Flipping Death is a silly and morbid good time.