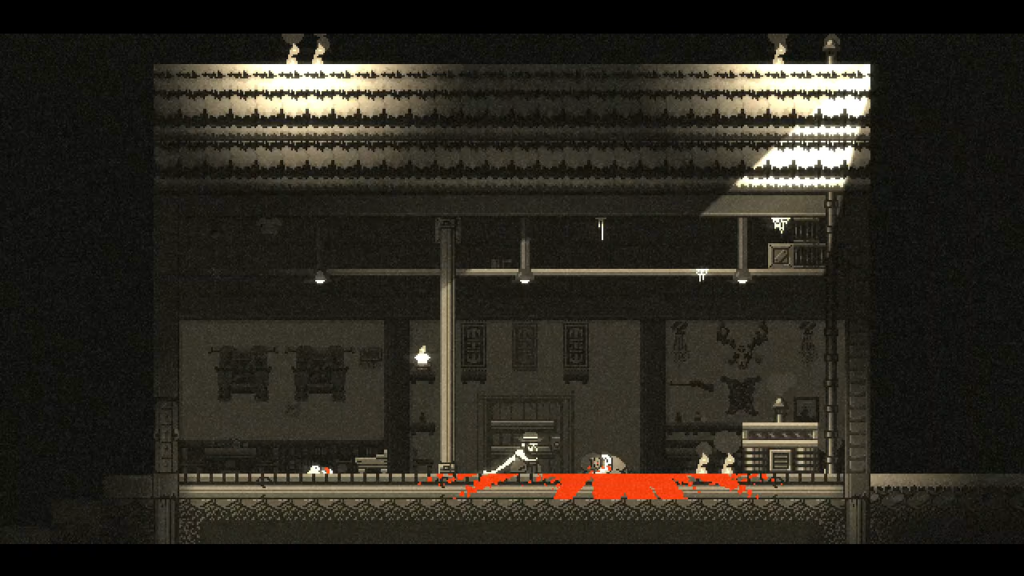

Gunbrella is a side-scrolling action platformer about a man named Murray searching for the man who murdered his wife and kidnapped his infant child. The plot kicks off as Murray returns from picking mushrooms to find his home in flames, his child’s crib empty, and his wife’s body lying on the bloodstained floor. The only clue to the culprit’s identity is a strange object left on the doorstep: A weapon that is both gun and umbrella. By riding a train between different towns, Murray searches for information about the Gunbrella, hoping that finding the unusual weapon’s owner will lead to his wife’s murderer and his kidnapped child. The hunt isn’t a safe one, and Murray finds himself wielding the Gunbrella in battle himself, unnervingly becoming more and more proficient with the very weapon responsible for his family’s fates.

The most interesting thing about Gunbrella is its title weapon. As its portmanteau name suggests, it contains elements of both a gun and an umbrella, and because this is a videogame, it gains the most fantastic elements of both its namesakes.

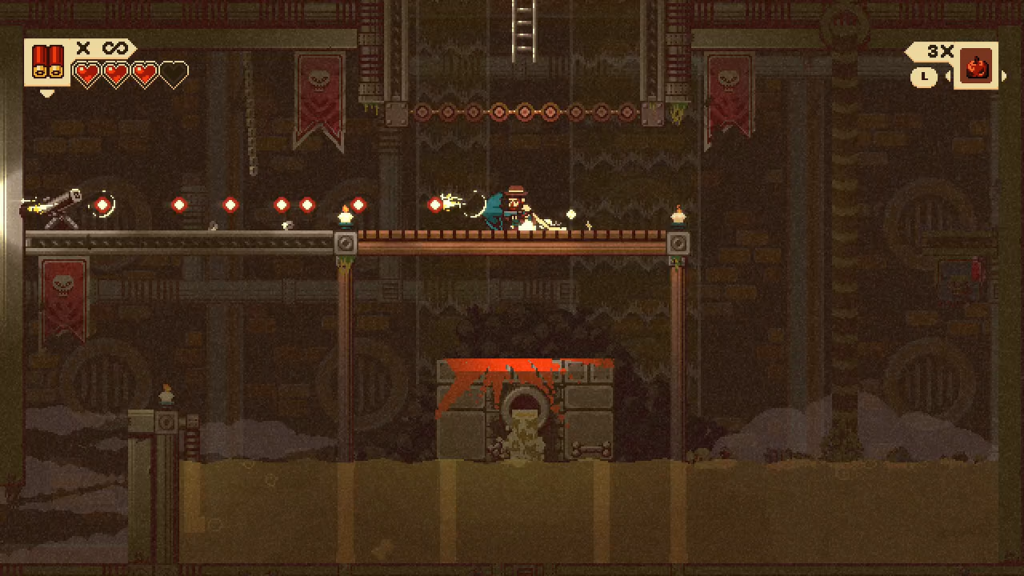

The Gunbrella’s gun half is a useful weapon for dispatching Murray’s enemies. Using the mouse or right joystick, I can point it in any direction around Murray while he remains mobile using the keyboard or left joystick. It fires an unlimited number of shotgun shells by default and certain enemies may drop limited quantities of specialized ammunition for it as well. As Murray progresses in his investigation, the Gunbrella’s shotgun functionality may be switched out for a long-range rifle, a grenade launcher, a heat-seeking rocket launcher, a flamethrower, and more.

The catch to all of these options is I never find much use for them. The default, infinite-supply shotgun rounds are enough to take out everything that gets in Murray’s way without much difficulty. Only its lack of range occasionally proves problematic. I find exchanging the extra ammunition for spare parts to be more useful. The parts can be taken to a tinkerer to upgrade the Gunbrella’s power and firing speed. The compounding loop this creates only undercuts the specialized ammunition more; the shotgun shells are already powerful enough, and selling ammunition to buy upgrades only increases its strength further. By the end of the story, I’m ignoring any pretense of strategy or preservation and firing as many powered up shotgun rounds into the boss’ faces as I can to great effect. As a weapon, the Gunbrella is so strong that even Murray’s greatest nemeses offer no compelling resistance.

The Gunbrella’s umbrella half is a useful tool to equal its use as a firearm. When the umbrella is opened, it acts as an impenetrable shield against enemy projectiles. If it is opened with precise enough timing, it can even reflect those projectiles back at enemies.

The umbrella half finds much more use in moving the player character around the world’s various environments. If Murray is jumping when the Gunbrella opens, he is hurtled a fair distance in the direction it is pointing. If it connects with electrified wires, Murray can zoom along them as though it is a grappling hook. As he returns earthward, the Gunbrella can be opened again to float him safely back to the ground.

All these wonderful applications suggest that an imaginative platformer is contained within this videogame’s digital boundaries. That is only a suggestion; all the creativity put into the Gunbrella’s creation is not reflected in the level design. It is basic and unmemorable. There isn’t a single moment in the seven hour runtime that makes me stop and go “wow, this is only possible in this specific videogame with this specific tool.” There are only tall platforms which must be launched over, wires to be grappled, and long gaps to be floated past. I have performed these tasks countless times in countless other platformers and often with far more imagination and challenge than presented here.

Combining the functions of a gun and an umbrella into a single device is novel. In every other way the Gunbrella is used, whether solving problems by shooting them or moving past obstacles with magic physics, this videogame struggles to be original, let alone memorable.

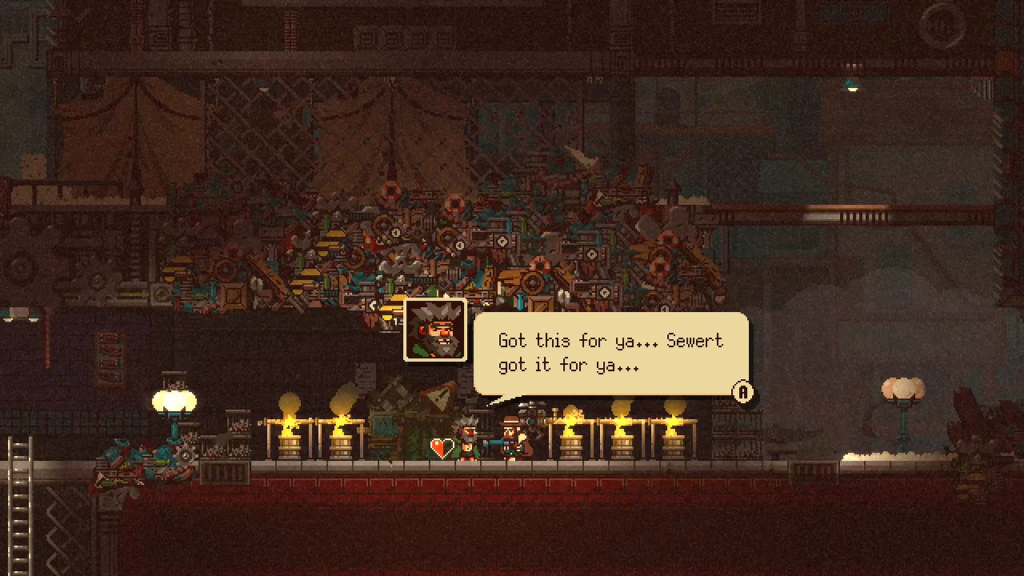

While Murray is shooting people and jumping over things, he encounters a cast of characters that provide the breadcrumbs of mystery leading to the man that destroyed his family. Each of them are encountered at stops along a single train line that leads through a vague world in decline.

At times, Gunbrella seems like a western, a revenge drama set in a bleak and almost exclusively brown world complete with a (toggleable) film grain effect. These western elements are disrupted at each of the train line’s different stops. Murray encounters a murderous demonic cult, a junkyard filled with dieselpunk scrappers, an invasion of ghosts hunted by a repentant priest and a vengeful widow, and a utopian society powered by literally human resources. All of these events are wrapped in a story about the negative impacts of fossil fuels on the world.

Once again, I lament Gunbrella’s predictability. In the junkyard, Murray fights a scrapper with a hammer. When the fight is over, the scrapper demands that Murray finish him off. If Murray complies, then his continued interactions with the scrappers are more contentious. If Murray spares the scrapper, then they become allies and Murray enjoys friendlier relations with the clan. I encounter several binary moral choices like this over the course of the plot, and none of them have any real impact on the direction the narrative follows. Like the platforming, these are rote design choices that do nothing to engage my interest.

Even Murray’s motivation is predictable. The single event that motivates him is the murder of his romantic partner. Going straight to that cliched, misogynistic fridge should have been a warning sign of what I was about to encounter in Gunbrella. Nothing that happens is surprising, let alone interesting, or even original. I let the plot wash over me as I sit, unbothered and unmoved.

When I press the pause button, I see a status meter for Murray’s three upgradable characteristics: The Gunbrella’s power, its reload speed, and how many heart containers Murray has. He can earn half a new heart by solving the problems of non-player characters who live near each train stop. With six half-hearts, then Murray’s heart container meter is full. Confoundingly, I continue to find more half-hearts after this point. It’s as though the videogame itself doesn’t fully account for its own possibilities, continuing beyond an assumed endpoint. It suggests to me a lack of planning, of knowing where the videogame begins, where it will go, and how it will end. Gunbrella feels as though it was imagined as it was made.

I feel this also in how the player character’s name is revealed. I have referred to him freely as “Murray” throughout this review, but the videogame treats it as a midplot twist. When Murray reaches the end of the train line, plot events cause a fundamental change in the state of the world, prompting him to return to previously visited areas. The choices he made on his first visit impact the state of the different towns upon his return and it is only during this return trip that he is openly referred to as Murray. Up until that point, his name is treated as an irrelevant mystery, like Clint Eastwood’s character in The Man With No Name trilogy. It feels like the story’s narrator grew tired of referring to Murray solely by pronouns and invented a name for him on the spot.

The revelation offers me no new insight into who Murray is as a character. He’s still the same silent, scruffy, vengeful avatar who solves every problem he encounters with the very weapon that ruined his life. If that’s meant to be a tragedy, I did not glean it from the narrative. Murray trundles between stops on the train line, inevitably drawing closer to discovering his child’s fate, determinedly pursuing an obvious ending I am never given a reason to care about.

I am dismayed to be constantly disappointed by Gunbrella. Despite the imagination suggested by its unusual titular weapon, the entire videogame is run through with rigorously by-the-numbers design. I can feel the design trope checklist being marked off as I play: Shoot things. Jump over things. Make moral choices. Experience consequences for choices. Murder wife, pursue child, die tragically. I could ignore any or all of these aspects if I experience more than fleeting moments of enjoyment while playing Gunbrella. Instead I am left listless, bereft, and bored.