Ravenlok is a 3D action and adventure videogame about a heroine who is pulled into a magical world terrorized by an evil Queen. I play as a young girl whose family has inherited a farm from her aunt. The property is strewn with strange clocks, paintings of fanciful creatures, and a grimy old mirror. As the girl cleans the mirror, she is pulled into it by a crescent-shaped crook. Emerging from a blooming flower in an overgrown garden, the girl meets a giant rabbit named Finn who explains that the girl is Ravenlok, the one prophesied to defeat the evil Queen and free the Land of Dunia. Equipping herself with a sword and shield, the girl sets out to explore the land and find the three keystones that will open the gate to the Queen’s castle and their predestined battle.

At its heart, Ravenlok is an adventure videogame. It concerns itself mostly with placing barriers in the player character’s path which can only be overcome by finding the right macguffin and inserting it in the right spot or giving it to the right non-player character. Every step of progress made through the story is represented by these metaphorical, or literal, key-and-lock puzzles.

I am introduced to these familiar mechanics the moment the story begins. The first task is to help the player character’s parents find objects around the farmhouse. Her mother needs a key to wind the many clocks on the farmhouse’s walls, while her father has lost his toolbox. The player character is next sent to search for the key to the barn. Inside, she finds the mirror, but needs a washcloth to clean it. Once all of these items have been found and delivered—once all of these keys have been inserted into their locks—then the girl is pulled into Dunia and the story truly begins. This series of events, taking about five minutes in total, is a microcosm of my progression through the four hour story.

Locks that need to be opened are spread all across Dunia and it is not always obvious or logical where their keys may be found. When I do discover a key, I am never left in a moment’s doubt where it should be delivered as all locks are tracked in a detailed quest log. Even if the quest log weren’t there, it wouldn’t take much effort to find where to deliver a macguffin. Dunia doesn’t have enough space to effectively hide anything.

I like to compliment videogames for restrained and efficient design, and I especially enjoy indie videogames since they often defy the bloat and sprawl that has come to typify high budget videogames from big name developers and publishers. So when I say that the Land of Dunia is small, I mean that it feels cramped and limited. The player character’s journey takes her to many mysterious and dangerous places that each consist of three or four rooms at the most. This is best felt in the clock tower, a space described as a museum filled with deadly malfunctioning clockwork exhibits. It contains a grand total of two rooms, the tower’s bottom and top floor, and two boss fights. It doesn’t feel like a tower. It barely feels like a complete space.

When the player character is not traversing Dunia in search of keys and locks, then she is fighting the monsters and evil servants of the Queen that lurk across the land. Like its adventure game design, Ravenlok doesn’t complicate what has worked in other, similar videogames. The player character can swing her sword, block with her shield, and dash away from enemy attacks.

The sword is a curious addition to the canon of fantasy videogame action heroes. When the player character finds the sword, she describes it as “heavy.” I would never know that from how it functions. The player character whips the sword through the air as though it weighs nothing at all. Each swing happens in an instant, and may be followed up with another swing immediately after, sending me tumbling into a habit of pressing the attack button as many times as I can to drive the player character’s attacks. The text may describe the sword as heavy, but it feels like a blade of grass.

Defensively, the player character is nimble, but fragile. Her shield is sluggish to raise and limited by a stamina meter that drains with every absorbed blow. I find it easier to ignore its existence. This leaves the player character’s dash ability as the primary way to avoid enemy attacks. It doesn’t travel very far, but like sword swings it may be used repeatedly without penalty. Whether I’m fighting a pack of smaller enemies or one of the giant bosses, every fight is the same: Dash willy-nilly away from enemy attacks, and respond with a flurry of sword swings in the following lull. When the player character does take damage, she is easily healed by dirt-cheap potions.

The more interesting layers to combat are the special abilities the player character learns at key milestones in the story. The two sword skills aren’t that impressive; they are difficult to aim, with the result they often deal less damage than basic sword attacks. More useful are magical spells, the first a cluster of ice orbs that fly at targets like guided missiles, the second a flood of fire that damages anything that stands upon it for a short time. There is no resource to use these abilities. Each of them has a short cooldown and may be used again as soon as that cooldown ends. As enemy groups become more dense and bosses become larger and more aggressive, my strategy shifts to focus on spell damage almost exclusively. Perfectly placing a wave of fire under a large pack of enemies is the most satisfying thing I accomplish.

Like its adventure puzzle-solving elements, Ravenlok’s combat sits complacently at a bare minimum of competence. There are ideas here, but the lack of weight to the player character’s attacks and the ease with which her best abilities may be exploited makes participating in combat feel unrewarding. Like the locks that stand in the player character’s way, each pack of enemies and each boss encounter is another roadblock on the way to the ending and not a satisfying component of a cohesive whole.

It’s difficult to ignore how heavily Ravenlok cribs from Alice in Wonderland. The player character is pulled through a magic mirror by a white rabbit. She wanders across a bizarre and often contradictory land, attends a giant tea party, explores an overgrown labyrinth, and ventures into a sinister mansion. She meets many unusual and friendly creatures and battles the Queen’s playing card guards. Just when I’m most exasperated by Ravenlok’s plagiarism, that I am almost convinced it believes I will not recognize its obvious inspiration, the player character enters a boss battle with quarrelsome twin robots named Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee. It is here I realize there is no intended deception, rather there is a lack of imagination. When adapting a place literally called Wonderland, that’s an unignorable flaw. Dunia is not wonderful and has a dearth of wonder.

Perhaps I could glean more wonder if anything that happens in Ravenlok were treated as unusual, or even interesting. The player character is nonchalant about being whisked away to another world and charged with its rescue. Non-reaction is her default response to everything she encounters. She is never frightened, or confused, or happy. This lack of characterization extends to the entire cast. I don’t feel for anyone because nobody seems to feel anything. Even the villainous Queen is empty. I get some sense that she has somehow frozen time in Dunia, but this is glossed over quickly in the dialog and has no actual impact on how I interact with Dunia. I’m not entirely sure it’s really happening.

I can’t even be tempted to offer a compliment to Ravenlok’s audacity at outfitting its Alice with a sword and shield and sending her to swashbuckle across Wonderland. Disney and Tim Burton already did in 2010, and even that adaptation owes at least some of its spirit to American McGee’s horror take on Wonderland.

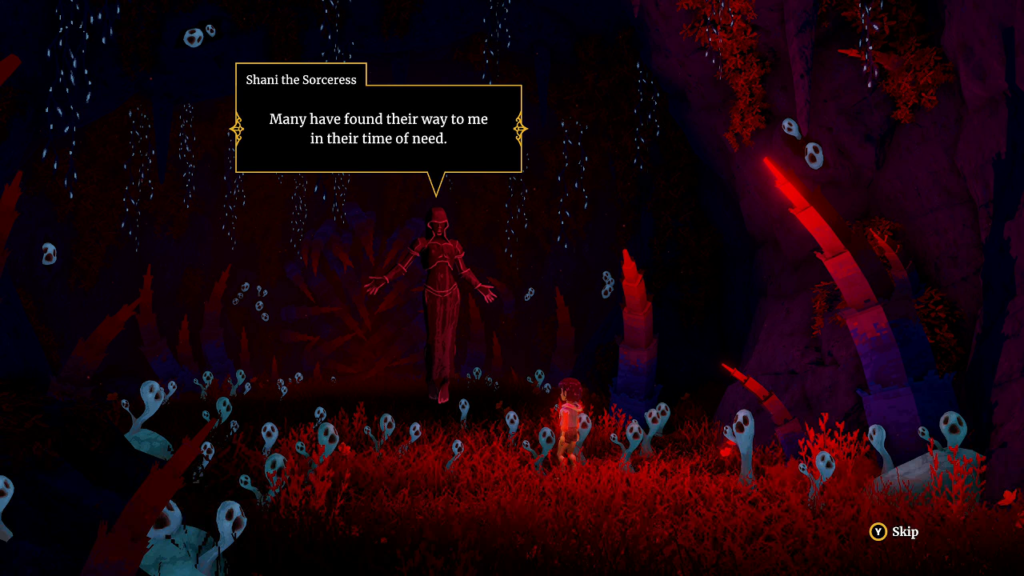

Ravenlok isn’t interesting to play or to exist in. It is, at least, interesting to look at. Character and environment designs are intricate and typified by a dark and moody color palette that gives Dunia an appropriately sinister feeling. From the black and purple hues of the Mushroom Forest, to the opulent reds of the Mask Mansion, to a botanist’s lab in the heart of an ancient labyrinth choked with a green miasma, the visual design throughout is striking. If this videogame succeeds only minimally in its design, plot, and characterization, it at least accomplishes a real sense of atmosphere through its use of color.

And yet this use of color feels only surface-level because of the features in Dunia they are applied to. Characters and objects made from smooth, round, high-poly assets exist alongside characters and objects with jagged and flat features constructed from voxels. I recall another story about a girl who is pulled from her home on a farm to a magical and far away land which differentiates its two settings by radical shifts in color and design. There is none of that purposeful composition here; voxels and polygons intermingle on the player character’s farm just as readily as they do in the Land of Dunia. If there is a reasoning behind some of Ravenlok’s features looking like they come from a big budget AAA videogame and why others look like they were built in Minecraft Creative Mode, I cannot discern it.

Ravenlok is pure videogame filler. It isn’t substantial enough to be satisfying, engaging enough to be fun, or impactful enough to be memorable. Yet I cannot accuse it of being bad. It held my attention throughout and made me think about solutions to puzzles and when to apply the player character’s combat abilities. I can say little about it other than it occupied four hours of my time neither happily or unhappily. About the best compliment I can give is it’s an easy source of videogame achievements, pushing out dopamine-pumping popups every few minutes as the player character accomplishes seemingly any task. There is nothing for me to get excited about here. It’s a wonderland devoid of wonder.