Double Dragon Gaiden: Rise of the Dragons is a retro beat ’em up that reimagines the Double Dragon videogames in a new setting that draws from every entry in the genre-foundational series. It is the year 199X and following a nuclear war, New York City has been taken over by four competing gangs: The Killers, the Royals, the Triangle, and the Okada Clan. The remaining citizens elect a new Mayor, who recruits Billy and Jimmy Lee of the Sōsetsuken Dojo to use their martial arts training against the warring gangs and restore order. With the help of their cop friend Marian, their guardian Uncle Matin, and a growing roster of unlockable characters from across the series, Billy and Jimmy set out to reclaim a crumbling New York City from the gangs, who grow in power with every choice I make.

Part of what makes beat ’em ups great is their simplicity and Double Dragon Gaiden wisely avoids overcomplicating its core design. My chosen player character moves from the left side to the right side of a side-scrolling environment. At key points along this path, the screen locks in place and one or more waves of enemy thugs appear. The player character can defend themselves from these enemies with melee attacks using a single attack button that cycles through a short combo each time it is pressed. When every enemy wave is defeated, the player character is allowed to continue through the level.

Each player character’s simple attack combo is embellished by a unique “action” attack. Action attacks confer some unique functionality, though many are shared between multiple characters. Of the default player characters, Billy and Jimmy can grab an enemy and either punch them until they run out of hit points, or throw them across the screen. Instead of punching and throwing while stationary, Uncle Matin uses his incredible strength to grab, lift, and carry enemies above his head. Marian is the most unique of the quartet; instead of grabbing and throwing, she dashes forward and strikes with her police baton. What utility this provides over her regular attack I still have not discovered.

Where Double Dragon Gaiden complicates familiar beat ’em up systems is in its SP meter. As the player character fights, they build up the blue SP meter beneath their red hit point meter. When it is full and shining, they gain access to a number of useful skills.

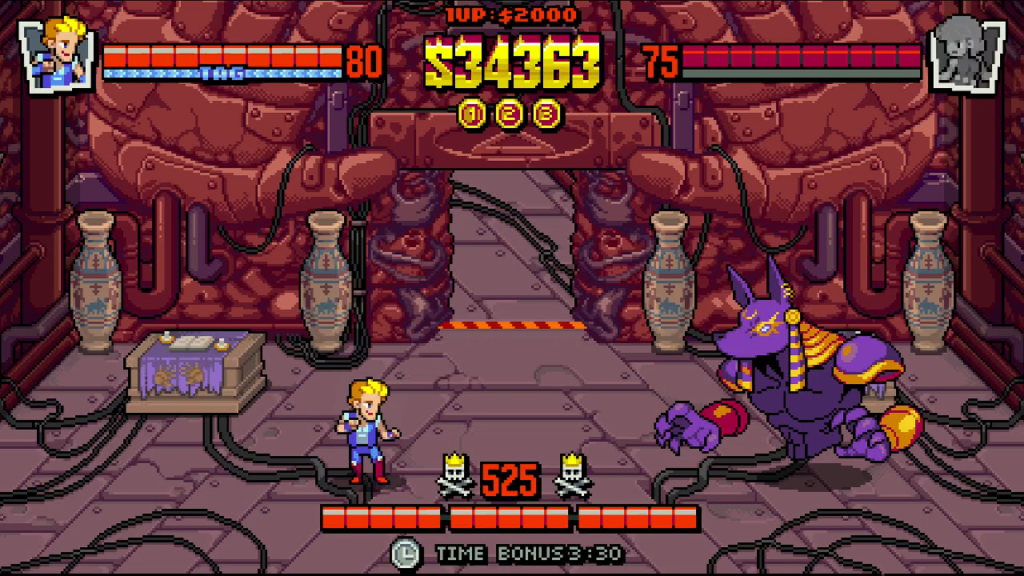

The most strategic application of a full SP meter is tagging in a partner character. When I begin a new campaign, I select any two unlocked player characters who work together to reach the end of the campaign. One remains on standby while the other fights. The partner on standby slowly regenerates a portion of their lost health, encouraging me to switch between partners often, especially if one of them comes out on the bad end of a tough fight.

The more practical and prevalent use of a full SP meter is to activate one of each player character’s three special moves, unique attacks which can devastate entire groups of enemies with a single application. There isn’t much notable difference between most player characters when using their basic attacks, but their special moves give them a real sense of identity.

Billy and Jimmy Lee’s special moves are good examples of contrasting abilities creating unique player characters. Billy’s Whirlwind Dragon performs a stationary spinning jump kick which can hit every enemy around him. Jimmy’s equivalent is Dragon’s Flame, a flaming uppercut that only strikes the area in front of him. Billy can also use Soaring Dragon, a jump kick that launches him forward, and Diving Dragon, a jump kick that can reach airborne enemies but only carries him a short distance. Jimmy’s equivalents are Dragon’s Rage, a forward lunge accompanied by a flurry of fists, and Dragon’s Claw, a leap into the air that grabs anything in its path—such as a flying or thrown enemy—and slams it down into the ground, creating a shockwave that damages other enemies.

Special moves are balanced well enough that I never feel regret or anxiety for trying to play as a variety of characters. Some special moves are plainly better than others, but those better ones are spread among all the player characters. Billy’s Whirlwind Dragon is more useful than Jimmy’s Dragon’s Flame, but the tradeoff is Jimmy’s Dragon’s Claw is more useful than Billy’s Diving Dragon. In fights where Whirlwind Dragon can draw in and defeat lots of melee enemies, Billy excels. In fights where Dragon’s Claw can seize a flying enemy and slam it into a pack of other enemies, Jimmy excels.

The exception to this relative balance is Marian. She specializes in firearms whereas most enemy attacks are designed around melee combat. Her basic attack is a flurry of gunfire from her sidearm, letting her shoot enemies from across the level with little risk to herself. Once I discover her Bazooka special demolishes almost every boss, I reach the opinion there is little reason to have anyone other than Marian as a tag partner. There are a few scenarios where she feels like a bad choice compared to a melee combatant, but for the most part she trivializes any situation she enters.

There is a more important reason to use special moves than their sheer power. They can also be used to heal. Defeating three, four, or five and more enemies with a single special move causes healing items of increasing effectiveness to drop. This is called a Crowd Control. Since defeating enemies with special moves boosts the SP meter, it’s common to earn a Crowd Control and immediately be able to use another special move, potentially earning another Crowd Control. With practice, guile, and knowledge of a level’s enemy spawning patterns from my part, the player character can leave a trail of hot dogs, hamburgers, and turkey dinners on the ground behind them. Keeping their health meter topped out is almost never a problem.

In addition to earning food from Crowd Controls, special moves also cause enemies to drop money. Money is the most important thing to collect as it drives almost every other way that I interact with Double Dragon Gaiden.

Both my primary player character and their tag partner share a single life. If they expire, I may buy another life using the money that spills from enemies when they are defeated by a special move. The price for a new life gets exponentially more expensive the more are purchased. This mechanic, along with Crowd Control, inextricably ties the player character’s continued existence with their success at executing special moves. The more enemies they defeat with special moves, the more they gain access to health and extra lives.

Money’s second use is for buying upgrades. At the end of each level, or “sector,” I am presented with a selection of random upgrades for both the player character and their tag partner. Purchasing one of these upgrades improves that character for the remainder of the current campaign. I can increase their hit point total, increase the damage of their attacks, or reduce the cost of using special attacks, among other impactfully mundane choices. Investing a few upgrades into special moves creates an immensely satisfying feedback loop of power and profit; spending money improves special moves, which earns more money, which can be spent on further improving special moves, which earns still more money.

The last interesting wrinkle Double Dragon Gaiden introduces to familiar beat ’em up mechanics is how I progress through its campaign. I can choose the order the player characters confront the four gangs. The choices I make alter what happens in those levels in dramatic ways.

My first choice is the most momentous. At the outset, Billy, Jimmy, and their allies haven’t made themselves known to the Killers, the Royals, the Triangle, and the Okada Clan. The gang they attack first is caught by surprise, putting up a weak resistance before their gang boss is fought at the end of a single sector. The second gang they challenge has some notice, so the player characters must fight through two sectors filled with more and slightly tougher enemies before they reach the gang boss. The first sector also adds a new sub-boss fight, usually against a group of powered-up standard enemies, but sometimes a sub-boss from a previous Double Dragon entry will recur instead. The third gang fought likewise adds a final, third sector and another new boss fight.

This system of adding progressively more sectors to each gang’s base is where Double Dragon Gaiden derives much of its replay value, an important factor in the traditionally short and undynamic beat ’em up genre. To see the full version of every gang’s base, I have to finish the campaign at least three different times. If the player characters raid the Okada Gang first, I only see the first floor of a hotel they have converted into a casino. Visiting them second reveals a hidden tunnel behind a book case, leading to a cliffside where boulders fall down on the melee below. Their third sector is the interior of a tenshu, its hallways filled with trapped spears that thrust from the floor while enemies emerge from sliding shoji doors.

When the player characters challenge the final remaining gang, it receives its most transformative addition. Instead of a new sector, the final gang’s boss is transformed into a new version that adds an extra layer to their original mechanics.

When the Triangle gang is fought first, second, or third, their boss Anubis is an ordinary man with seemingly magical powers that summon poison clouds, paralyzing lightning, and flashes of light that reverse my control inputs. During many of his attacks, I can glimpse the faint spirit of a jackal channeling these supernatural abilities. When Anubis is fought last, the man is replaced by the god, a giant statuesque jackal with disembodied hands. This powered up version moves faster and with greater power, providing a much greater challenge to overcome.

It doesn’t take me long to realize the order in which I choose to defeat the gangs has a great impact on what difficulties I will encounter during that campaign. Some levels are more difficult than others. Some bosses are more difficult than others. Besides its regular enemies, the Okada Clan’s base is filled with falling boulders, trapped floors, and flying drone enemies that make it much more difficult to travel through than the Killers’ base, a tower filled with half-finished floors and the prerequisite beat ’em up elevator sections.

The bosses have an even greater impact on difficulty. M.G. Kelly, the Killers’ leader, likes to fight from a distance, strafing the entire battlefield with his machine gun. He can be dangerous, but manageable with care. His transformed mode adds a new layer to the fight that makes him take much longer to defeat. In contrast, Lady Okada gets a big visual upgrade but is really not much different than her basic form. I’m presented with a tricky choice: Have an easier level but a much more difficult boss, or a harder level and an easier boss. As with the balance of special moves assigned to the different player characters, I infer a sense of purposeful design in each level’s potential difficulty.

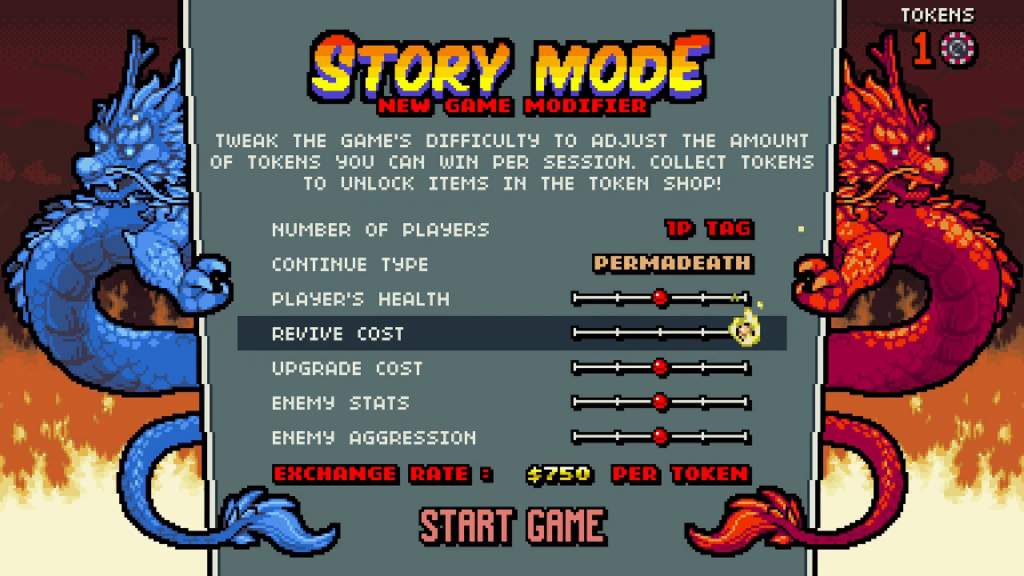

While the order I choose to take on the gangs can have a progressive effect on a campaign’s ongoing difficulty, I am able to impose immediate difficulty changes when starting a new game. By moving sliders up and down on various modifiers, I can adjust aspects like the player characters’ total health, how much upgrades and extra lives cost, and further increase the power of enemies. I’m allowed some latitude in these choices; each modifier defaults to a middleground, so I can make the campaign easier or harder as needed.

These modifiers are the last feature that interacts with money earned from special attacks. At the conclusion of a campaign, whether I get a game over or defeat all four gangs, the player characters’ total remaining money is converted into reward tokens. The more difficult I make the initial modifiers, the more favorable the exchange rate becomes.

Tokens are how I gain access to Double Dragon Gaiden’s unlockable features. For one or two tokens, I can unlock hints that explain some of the more opaque nuances of beat ’em up design, and Double Dragon Gaiden in particular. This makes this videogame an excellent entry point into the genre. Not everything I learn here applies to all beat ’em ups, but many of them are just as applicable, particularly the importance of using all of a player character’s abilities to manipulate enemies into controllable groups. I can also unlock concept art and music tracks.

The most important things tokens unlock are new player characters. In addition to Billy and Jimmy Lee, Marian, and Uncle Matin, every unique sub-boss and gang boss are fully playable in future campaigns after they are unlocked. Many of them are lifted directly from previous Double Dragon videogames, while the rest are at least based on previous villains. Seeing these characters again and actually being able to play as them is a real treat for series fans.

I only wish there was more to see than new characters. Seeing every permutation of each gang’s expanding and evolving base adds some replay value, but it still only takes a handful of campaigns to see everything on offer. This is part of the beat ’em up experience. Enjoyment is found through developing mastery of existing, limited content, not through exploration of continuously expanding content. Double Dragon Gaiden tips just enough over this edge, offering a suggestion there is more to see. I am intrigued by the suggestion, but I soon discover there isn’t much more there. This leaves me disappointed, whereas in another beat ’em up I would be unsurprised to find a single campaign and nothing more.

Double Dragon Gaiden is a great collection of new ideas introduced to the familiar beat ’em up space. Yet not that new. Many of its mechanics draw heavily from the same developer’s earlier Devil’s Dare. It works simultaneously as a celebration of the Double Dragon series and as an entry point to beat ’em ups, a genre whose simple concept belies its mechanical depths, creating a false impression of difficulty. Special attacks and Crowd Controls ingrain some of the genre’s most important strategic concepts into the player in an approachable way that makes them feel satisfyingly powerful. The downside is there isn’t much here for veterans, which is especially a problem for a game partially built on fanservice. Even with the difficulty modifiers cranked, systemic knowledge trivializes challenge. Double Dragon Gaiden is an entertaining time, but not a robust one.