Videogame developers in the 1980s had a problem: How does one make a car racing videogame that creates a sense of speed and forward motion? The solution for most was to have the player view the action from a bird’s-eye, top-down perspective, a wonderful approach to racing that persists in retro design to this day. But how might a view captured closer to a driver’s perspective work, especially without using polygons? Polygons had been used in videogames for years by that point, but they were often static or their movement across the screen was too slow to service a satisfying race. It was Yu Suzuki, leading a team at Sega, who devised a way to create a convincing illusion of forward motion from a ground level, forward facing perspective using two dimensional sprites.

By taking a sprite of a common roadside object, such as a tree, and rapidly expanding its size, it suggests that the viewer is approaching the object at high speed. Make the tree disappear when it reaches a certain size, and it suggests the viewer has passed beside it. Put two expanding trees on either side of an expanding gray square, and a small road segment is created. Line up hundreds of these road segments in a row that twists to the left and right, and they become a race course. Add a car that sits in the middle of the screen and a scenic backdrop that pans back and forth as the player’s inputs follow the track’s curves, and a complete illusion forms.

When the player presses the accelerate button, the car moves “forward” along the track. The trees and other objects on either side of the road pass by, expanding and disappearing with increasing speed. Soon they whip by at least a dozen times a second, turning into a colorful frenzy of motion. The car never moves, but the illusion of speed created around it is hypnotizing. The result is Out Run, one of the most influential racing videogames of all time with an unmistakable and iconic visual design.

80’s Overdrive is a ballad of unembarrassed, gushing adoration for Out Run’s visual style. It reproduces its method for creating a race course from expanding sprites, reimagined with current technology and high-definition graphics, then soaking them in neon and nostalgia to create a set of 37 individual tracks.

While 80’s Overdrive is inspired by Out Run’s visuals, it would be incorrect to say it is an all-out copy. In Out Run, my opponent is a ticking clock. 80’s Overdrive’s main Career mode is a straightforward race against nine opposing racers.

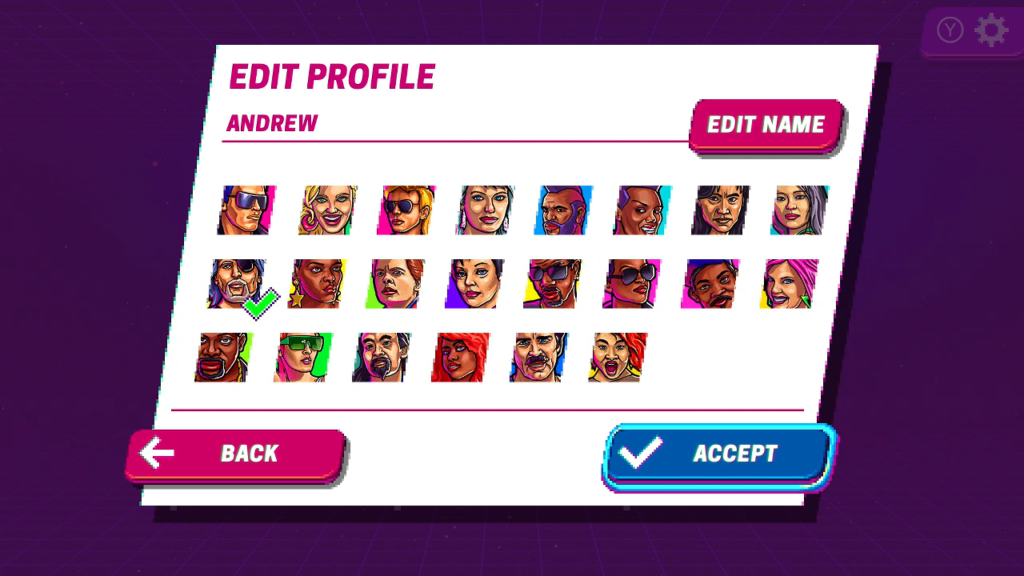

Before I may begin Career mode, I have to create a profile. After entering my name, I select a profile picture which serves as my avatar. Each profile picture is an uncanny pop art-style portrait of a celebrity from the 1980s. Choices include Jackie Chan, Sylvester Stallone, Mr. T, Grace Jones, Madonna, and The Fresh Prince. It’s a surprisingly diverse collection considering the limitation to 1980s pop culture. Ultimately I choose a portrait resembling Kurt Russell as he appears as Snake Plissken in Escape from New York.

Once I have made my profile, I may begin racing through the Career mode. There are stars strewn across a map which represent each course. I earn crowns for placing first, second, or third place in a race. The more crowns I earn, the more courses I can access. I can choose two courses at the start. It is from these that I will expand the legend of my name.

When I select a course, I am given a brief preview of the roads where I will race. 80’s Overdrive represents illegal street racing, so I am competing against computer-controlled opponents on public roads filled with commuters. The amount of traffic on a course is often its most impactful factor. When I lose a race, it’s nearly always from a collision with a commuter rather than being outraced by a competitor. The number of lanes that make up the course’s road can make traffic better or worse; fewer lanes means there is less room to maneuver. The most difficult courses have only three lanes where racers and commuters vie for space.

The last factor to consider is a police presence. They don’t appear on every course, but when they do they are not shy about endangering the lives of everyone on the road to stop the street racing. They first barrel into my car from behind, their appearance heralded by red and blue lights flashing on the road for several seconds. After this attempt, they speed ahead then come to a sudden stop directly in my path. Courses where they are present turn into desperate slalom courses where I must weave between aimless commuters and hostile cop cars while still keeping ahead of other racers.

Course previews also list the difficulty rating of competing racers, scored in half-star increments out of five. This rating feels nominal at best. I fall back to the first course a number of times with a car souped up for later challenges and the half-star ranked competitors there often keep up fine, sometimes even pulling into the lead and staying there. Rubber banding is an infamous aspect of racing game design where computer-controlled opponents perform beyond their car’s ability, to the point of offscreen teleportation, ensuring the player always feels like their position is being contested. I never feel like the rubber banding effect in 80’s Overdrive becomes obnoxious. I can sense it happening, but I rarely feel like I am being treated unfairly compared to my fellow racers.

The way traffic behaves feels like it has a greater bearing on the race’s outcome than on the competition’s difficulty level. Commuting cars drift back and forth across the road with no apparent purpose. They often turn at the last second directly in front of my car. When I first encounter this phenomenon my instinct is to turn away from potential collisions, potentially driving straight off the road into an obstacle. It takes several seconds for my car to automatically reset onto the road when this happens, often sacrificing my lead. I eventually learn that I need to brake and turn towards these foolish commuters to avoid them. The good news is, my competitors are treated just as poorly by unpredictable traffic. I eke out several last-minute victories when an opposing racer with a short lead suddenly crashes into a commuter who turns into their path.

In addition to earning crowns when I rank in a race, I also earn money. Money’s main use is upgrading my car. Cars have a pleasant arcade simplicity with three attributes to track and improve. A better engine makes the car move faster. Better steering helps the car make sharper turns, which becomes more and more of a necessity the faster the car is able to move. Last, I can upgrade the car’s bumpers, which reduces the damage it takes from collisions. It is possible to totally wreck my car by crashing too many times in a race, but I have to be especially haphazard for that to happen. Not once in my time playing do I even reach 50% of my car’s damage meter.

There are two paths I may take on purchasing and upgrading a car. I can spend money incrementally upgrading a cheap vehicle, or save my money for a more expensive car. The cheaper cars need more upgrades overall to reach their maximum potential, while the more expensive cars have fewer upgrades to purchase but require more investment up-front to own.

There isn’t really a compelling choice here. Every car is statistically identical once fully upgraded, so there is no advantage in the long run to holding out for the most expensive cars. The practical effect of this upgrade system is I can progress through the Career Mode with the Testosterando, the cheapest car, buying upgrades as I can afford them. Or I can grind the earliest races with an unupgraded car for hours to get enough money to buy the most expensive car, the Tensor V12. Whichever choice I make, either chosen car’s ultimate performance will be identical. All that changes is how much time I spend grinding and what sprite represents my car during a race. The choice is easy for me. I opt for the one that doesn’t involve grinding.

80’s Overdrive makes other annoying economic choices. Every single race has an entry fee, even the first one; the later the race occurs on the Career mode map, the more it costs to enter. It is also possible to spend all of my remaining money on a new car or an upgrade.

All is not lost if I go totally broke. Other racers will contemptuously offer me fifty dollars to clean their cars. This requires me to place a cursor over a still image of a car, hold down a button, and wiggle the joystick for a few seconds to earn the cash. If this weren’t annoying enough, the entry fee for the cheapest race is one hundred dollars, mandating I play the minigame twice to put myself back in the competition. Blowing all my prize money on a new upgrade, playing the cleaning minigame twice in a row, then replaying the very first race on the map is such a common occurrence I lose count of how many times I do it before completing every race.

This whole process only happens because of the entry fees which feel increasingly onerous and unnecessary as I accumulate crowns and progress through the ranks. I soon discover a workaround.

Though I must repay the entry free every time I lose, once I am in a race there is no penalty to restarting it from the pause menu and no limit to how many times I may do so. This feels like a cheat that goes against Career mode’s spirit, but that spirit of grinding out bad minigames and easy races with cheap payouts to put myself back in the competition after a loss is irritating enough that I don’t let it bother me. Once I embrace my unlimited retries, I breeze through the Career’s twenty remaining tracks in a few hours.

There is more to do once I have finished the Career. Time Attack is the main draw and where 80’s Overdrive feels most like its inspiration. Like Out Run, Time Attack places me at the beginning of a course filled with commuters, but no competing racers. When I reach that course’s end, it branches to the left and the right and seamlessly transitions into the next race depending on which direction I choose. Unlike Out Run, these branching paths do not come to a stop after five courses. They continue on into infinity for as long as I can keep the clock ticking.

I keep the clock ticking through two methods. I get a generous boost to my remaining time by transitioning to a new course. The other method is to weave with equal skill and recklessness through traffic. When I pass by a commuting vehicle, I can add one, two, or three seconds to my remaining time limit; the closer I come to touching another car, the more time I earn. As I get better at weaving through traffic and develop a faster car through the Career mode I can balloon my time limit beyond half an hour.

Getting good at Time Attack is like playing a potentially endless version of Out Run that descends me into a zen state. I know many players—myself included—to whom this is the most enticing prospect 80’s Overdrive offers.

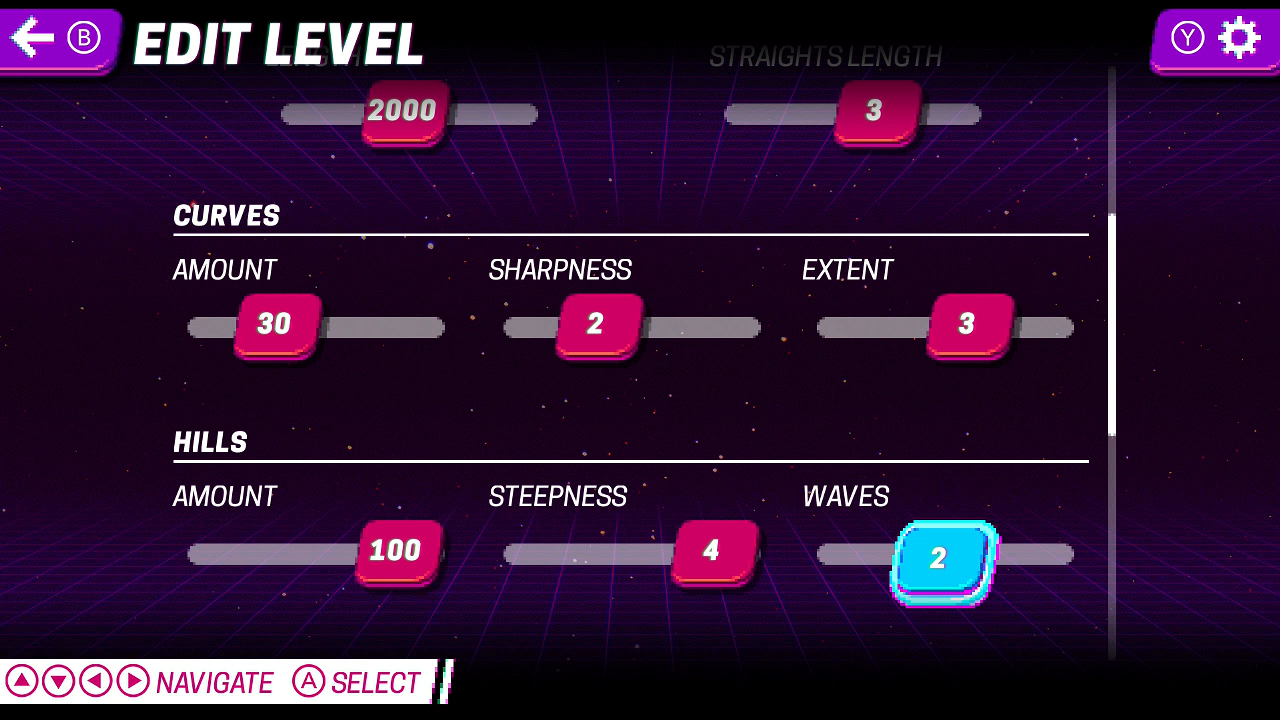

There is also a Level Editor, but it does not let me create levels in a traditional sense. I can input variables into sliders and dropdown menus that account for details like the course’s tileset, how many lanes, curves, and hills the road has, and traffic heaviness, among many other factors. I then race on a course generated from those inputs. I don’t meaningfully “create” anything. It’s uninteresting.

The best reason to play 80’s Overdrive is to see its adoring recreation of Out Run’s visual style in high-definition pixel art graphics. Its Career mode defies Out Run’s race-the-clock theme, pitting me against nine other racers on crowded public roads. It’s a fine time, but the necessity to spend money to enter races becomes a frustration. The real prize is taking the maxed out car I develop in Career into Time Attack, an endless drive through a neon-soaked pixelated landscape that truly recreates the spirit of Out Run. All that’s missing to make it completely authentic is a blonde passenger’s hair floating in the breeze. Out Run fans will get the most out of 80’s Overdrive, and I believe it may capture the uninitiated as well.