Bleak Sword DX is a lo-fi combat videogame about a lone warrior engaging in brutal battles against waves of enemies in small dioramas. It takes place in a nameless dark fantasy world where Prince Rhael has brought an end to the Second Age by murdering his brother and father using a cursed artifact called the Bleak Sword. Rhael crowns himself king, marking a Red Age where dark magic and abominations ravage the land, with the Bleak Sword unnaturally extending his life and cursed rule for over two hundred years. I play as a warrior who follows prophetic dreams to three magic stones that have the power to destroy the Bleak Sword. By conquering all the enemies in over 130 bite-sized levels filled with challenging, do-or-die combat, we can put an end to the Red Age, Rhael, and the Bleak Sword.

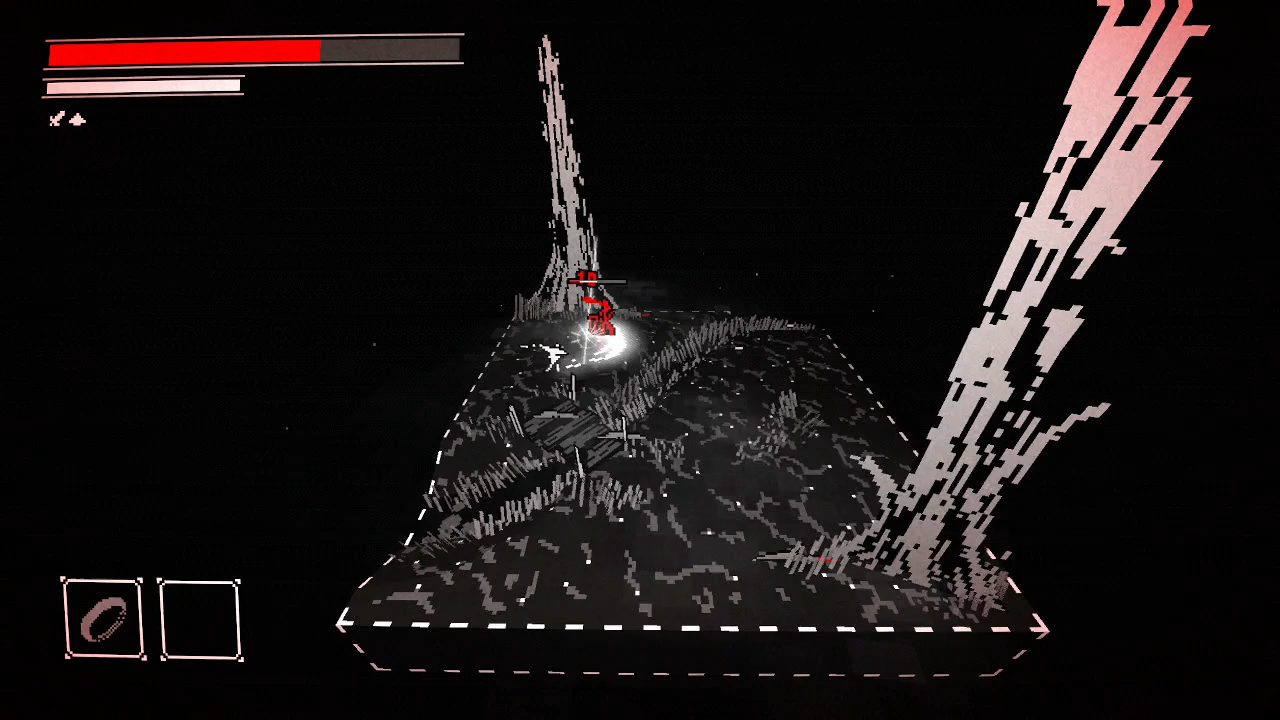

The most striking thing about Bleak Sword is its lo-fi graphics. The world, the player character, and their many opponents are composed of a handful of pixels and just three colors: black, white, and red. They look as though they have been plucked from an Atari 2600 videogame and dropped into a world made with technology forty years into their futures. This creates a stark and jagged appearance which suits a prevailing philosophy of simple violence and swift death.

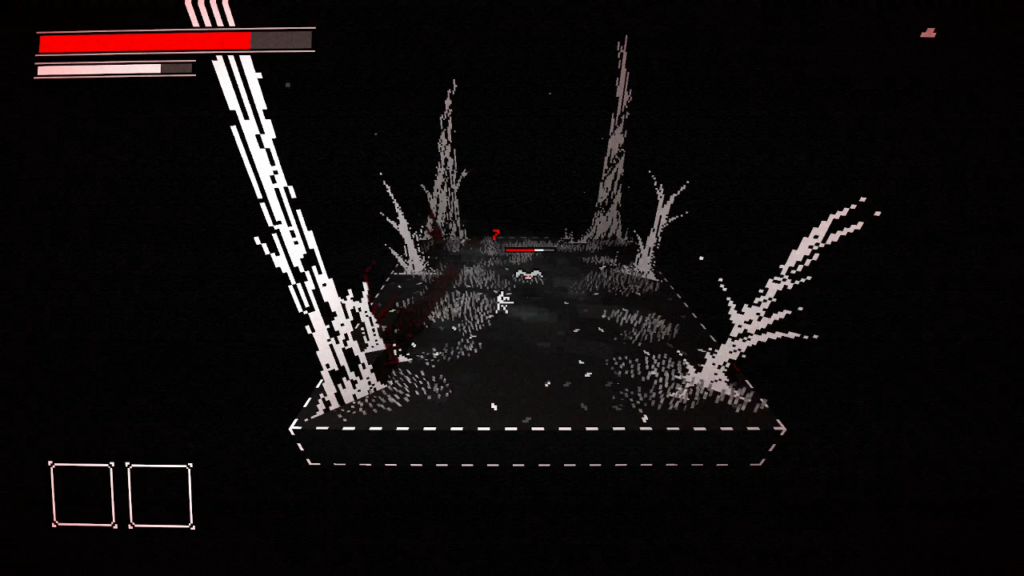

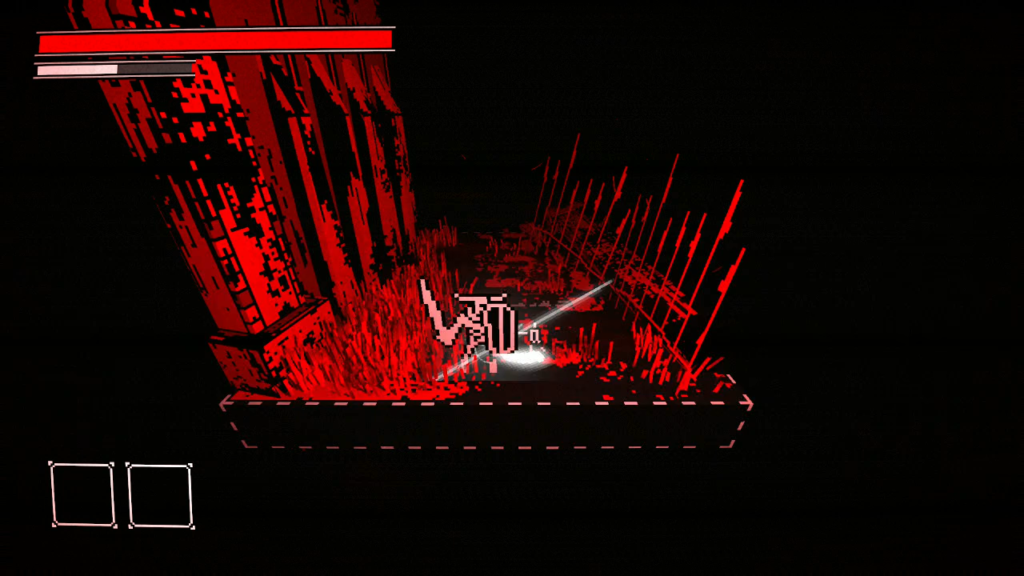

None of this is to say that Bleak Sword looks bad or cheap. Environments are more detailed than characters, using denser pixels mapped to simple polygons to create a world of wild forests, noxious swamps, snowy mountains, burning villages, and bloody torture chambers. All of these environments have embellishments that confer an extra kick of visual fantasy. Some stages are thick with fog which monsters prowl through to creepy effect. Several regions have rain and lightning effects which are so spectacular it can make seeing enemy attacks difficult (their intensity may be reduced in the option menu). In some stages, this rain turns red, and it’s up to my imagination whether this is a metaphorical representation of Rhael’s Red Age or if it is literally raining blood.

Bleak Sword is so committed to its aesthetic that cutscenes which begin and conclude most of the twelve regions are created with the cinematic rigor of a big budget, dark fantasy epic. They’re created with such earnestness that it doesn’t even occur to me to laugh as the camera zooms dramatically on the player character’s flat and featureless face with such regularity it would feel like a running gag in a setting that allowed for a sense of humor. For all its graphical simplicity, Bleak Sword never fails to communicate that its world is a desperate and bloody place to exist.

There’s a familiar fighting system in many indie videogames. An attack button causes the player character to swing their weapon. A dodge button makes them roll a short distance in the direction I press the joystick. A block button makes them raise their shield. Each attack drains a portion of the player character’s stamina meter. When the meter empties, they can no longer attack, demanding we wait a moment for the meter to refill before attacking again.

These systems create a methodical pattern where the player character and their opponents trade blows, attacking until their stamina is exhausted, acting defensively while it recovers, then attacking again. I usually encounter these ideas as a part of a larger videogame, creating the action the player character uses to interact with their enemies in between exploring the world, discovering treasures, and solving puzzles. Bleak Sword strips away these adventuring elements, letting the combat compose the entire videogame.

Each stage is a small, three-dimensional diorama that fits onto a single screen, no scrolling required. The diorama represents a small portion of the world as the player character journeys through it on their quest. Wherever they go, they are accosted by a wave of hostile monsters or a squad of Rhael’s soldiers. When all are killed the stage is finished and the player character moves on to the next one. Stages are short, no more than two or three minutes in length on the longest end, but they make up for this brevity with tenacious difficulty. Some of the hardest stages take me several dozen attempts to clear.

Bleak Sword is the kind of videogame where aggression leads to the player character’s quick end. Instead of being proactive, making the first strike against enemies, I must train myself to react to their attacks to succeed. Parrying enemy attacks is initially the most effective way to dispatch them. By raising the player character’s shield just as an enemy’s attack animation begins, they will be stunned for a moment, leaving them vulnerable to a counterattack. Counterattacks deal extra damage, cost no stamina, and are accompanied by flashes of magical energy around the player character’s sword. It is tactilely gratifying to pull off no matter how many hundreds of times I do it.

Over time, parrying becomes less prevalent as large enemies who exclusively use unblockable power attacks become the norm in most stages. Against these enemies, I must employ the player character’s dodge-rolling skill.

Dodge-rolling is where Bleak Sword departs most from the familiar combat mechanics it borrows. Dodge-rolling confers no invincibility frames, those precious milliseconds of invulnerability where an enemy’s attack will pass harmlessly through the player character. If an enemy attack connects with the player character, it will hit them, whether they are rolling or not. I must dodge away from all attacks, not try to roll through them as I instinctually assume. Absorbing this fact is the harshest learning curve I endure. To make this task easier, dodge-rolling consumes no stamina. I can send the player character rolling in circles around a stage as much as I want for as long as I want. When a stage fills with three power-attacking super demons, this can even feel like the most prudent choice.

This convenience does little to reduce the sheer aggravation Bleak Sword’s most difficult enemies instill. Many of the largest and most powerful enemies carry shields which make them effectively invulnerable when attacked from the front. They are skilled at always facing the player character and exclusively use power attacks, leaving their only moments of vulnerability those brief fractions of a second after they swing their weapon but before they raise their shield again. Since their attacks cannot be parried, I have to move the player character far enough away to avoid their crushing blows, but still close enough to get in a decisive strike before they raise their shield again.

Most of the player character’s deaths in Bleak Sword are due to my failure to find this precarious balance. Stages which feature large numbers of these shielded enemies become a stone wall to my progress forward. I grow from dreading to outright resenting their presence the closer we come to completing the warrior’s quest.

I can look past my own difficulty sparring with a particular enemy variety. That’s my failing, not Bleak Sword’s. What is Bleak Sword’s primary failing is how it punishes me when I get the player character killed.

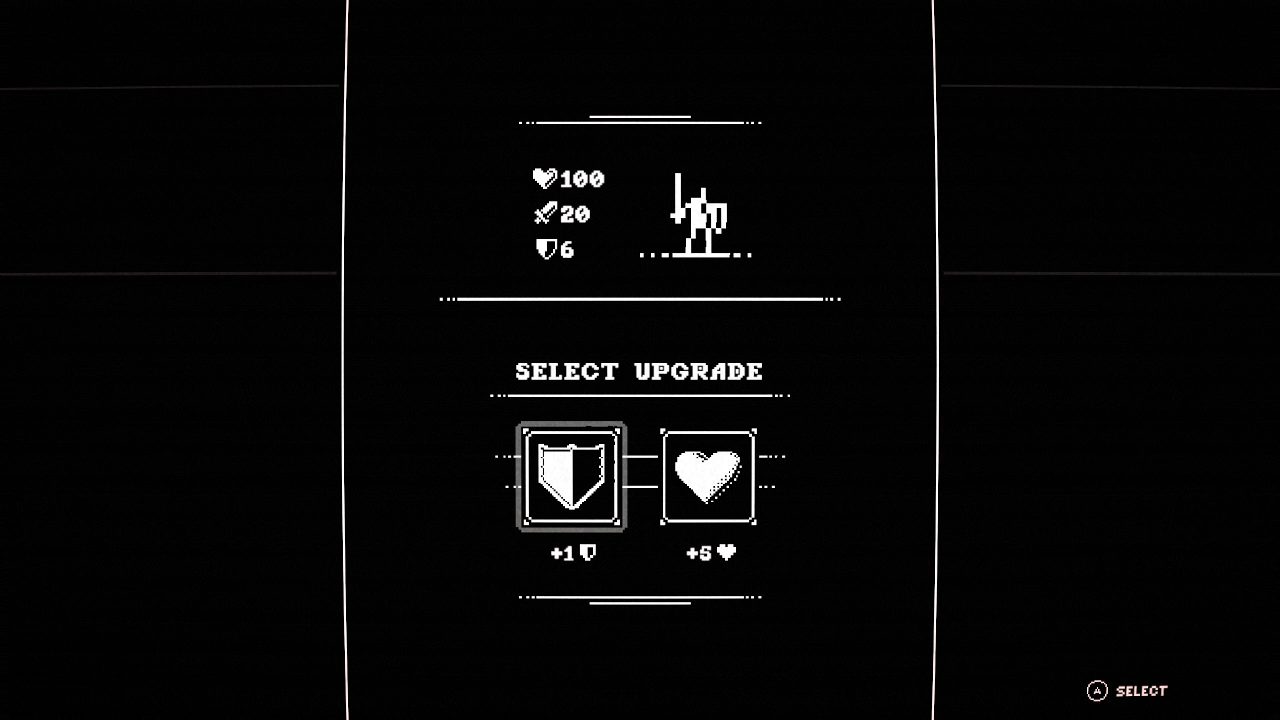

Despite its skill-based combat systems, Bleak Sword does feature RPG character development. Experience points are awarded upon the completion of each stage. When enough are earned, the player character gets a level up and may improve their weapon damage, their defense, or their total hit points. It’s in earning these experience points where leveling up the player character becomes difficult.

The first time the player character dies, they lose all of their accumulated experience points. I am given an opportunity to reclaim those experience points if I can complete the stage on the next attempt. If I fail for a second time, all those experience points disappear. Since completing a stage involves a lot of trial-and-error, of learning which enemies will spawn where and when, finishing a stage in two attempts is a lot to ask. I am mandated to finish multiple stages in a row, up to dozens at a time at higher experience levels, to gain a single point of growth.

This system is upside-down. Players who are more skilled will die less, retaining more of their experience points from stage to stage, ultimately having a player character that deals more damage and has more health. In my time with Bleak Sword, still learning how to play, I get the player killed a lot. They lose thousands of experience points to an abyss. My player character is a lower level on the same stage as a more skilled player’s, and so has a more difficult time with the same scenario. Bleak Sword punishes me for my learning curve. It’s a dispiriting situation.

The sheer number of experience levels I miss out on begins to catch up to me as I near Bleak Sword’s ultimate stages. I suspect the player character is underleveled around the middle levels. When I reach a point where expending an entire stamina meter still leaves an enemy with some remaining hit points, I accept that I need to stop and reconsider my options. The good news is Bleak Sword allows me to replay previous levels to earn additional experience points. The bad news is this means level grinding.

Grinding was once considered a necessary evil of roleplaying games, and this may still be the case for many players. I have discarded such pessimistic ideas. I now consider any time I am forced to play and replay a section to gain experience levels instead of focusing on my current place in the campaign to be a waste of my time. Grinding is a result of a fundamental failing in scenario design on behalf of the developer.

In order to boost the player character’s strength up enough to complete the later stages, I spend three hours grinding stage 11-1, a comparatively easy level containing no enemies with either shields or unblockable super attacks. My effort pays off and I’m able to complete the final stages, but not without sacrificing much of my feelings of goodwill. When my progress forward comes to a stop, the solution I find is not a new strategy or an epiphany of how Bleak Sword is designed. The solution is spinning in a circle to recover all the experience points I lose to a harsh death penalty.

As indicated by its title, Bleak Sword DX is a deluxe re-release of an earlier version. When I begin a new game, I am defaulted into the DX campaign, which describes itself as a “more challenging, longer and fun mode.” If I choose, I can play the “Classic” original campaign. It is broadly similar, but I notice it has fewer enemies and waits to introduce some of the more troublesome ones until later in the campaign.

When I’ve finished both versions of the campaign, there is still more to do. There are two additional difficulties beyond the default. For players interested in pushing themselves to their limits, the ultimate Bleak difficulty is listed as “soul crushing.” There is also a randomizer mode that rearranges which enemies appear throughout the levels, as well as an Arena mode where I see how many stages I can clear in succession using a fresh character that does not level up.

Bleak Sword’s simplicity is its main appeal, so I would not fault it for having only its story campaign and nothing else. Yet there is a surprisingly robust number of new things to do after seeing the credits if I feel inclined to continue playing.

I admire Bleak Sword for its simplicity. Simplicity is why I enjoy playing indie videogames. I find them to be an invaluable tonic for the time I put into modern AAA videogames which have become ever more bloated with systems and space. With its simple pixel art and combat design, I hoped that Bleak Sword would be something I would enjoy. I almost do. The one significant blunder it makes, taking away earned experience points because I fail at skills I am still developing, keeps me from giving it my whole-hearted recommendation. There’s a lot to admire here and a lot of fun for challenge-minded players. Just be prepared to grind to make up for your mistakes. The Bleak Sword demands it.