Curse of the Sea Rats is a side-scrolling non-linear platformer and RPG that takes its cues in equal parts from classics like Castlevania: Symphony of the Night and Saturday morning cartoons from the animation renaissance of the late 1980s and early 1990s.

The year is 1777 and a British Royal Navy ship is returning to England from the Caribbean, its hold filled with prisoners to be put on trial for crimes against the Crown. One of the prisoners is the pirate-witch Flora Burn who transforms everyone onboard, prisoner and sailor alike, into giant anthropomorphic rats. During the chaos she frees her crew from their bonds and they flee to the nearby Irish coast with Admiral Benjamin Blacksmith’s young son as a hostage. With his crew occupied repairing the damaged ship, the Admiral reluctantly recruits the four remaining prisoners to recapture Flora Burn and rescue his son. If they succeed, he will arrange to have them pardoned. I choose to play as one of the four prisoners and set out on an adventure that will earn them their freedom.

If there’s anything that can be raved about in Curse of the Sea Rats, it’s the artistry of its character designs. They are brought to life on screen by expressive traditional animation techniques that send me back to weekend mornings watching cartoons on a big, boxy television. The four player characters are particularly interesting when I consider some of the conflicts around the year 1777 that involved, and were frequently caused by, British colonialism.

David Douglas is a soldier in the Continental Army, captured by the British army during the American Revolutionary War. Another hero is Bussa, an escaped slave and freedom fighter from Barbados whose background evokes the uprisings of enslaved peoples in the Caribbean islands during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Buffalo Calf is a Cheyenne woman who was arrested while freeing horses from the British army. The many political complications between Indigenous American cultures and the invading European colonists is too weighty a topic to address concisely here, but suffice to say none of the native peoples benefited from their encounters. Rounding out the quartet is Akane Yamakawa, an Onna-bugeisha who was captured on a “secret mission” in North America. What a Japanese warrior is getting up to in North America that would get her ensnared by the British army is not totally clear, but 1777 is in the thickest part of Britain’s growing interest in a trade relationship with Japan.

Portraying these characters through Saturday morning cartoon-inspired animation is both a good and a bad thing. The animation renaissance era saw much more effort and funding put into fluid and detailed animation for cartoons intended for broadcast television. It was also an era that perpetuated many racist tropes, many of which I see echoed here. We never get to see any of the player characters in their human forms, yet their racial coding still shines through in obvious ways.

David Douglas is the most conventionally heroic character. He’s a swashbuckler, wielding a cutlass and a flintlock pistol in combat, calling to mind the roguish heroes of 1950s cinema exemplified by actors like Errol Flynn. He occupies the first, leftmost slot on the character select screen, seeming to give him preferential treatment. It’s the white American patriot who I am always prompted to play as first.

David Douglas’ obvious counterpart is Bussa. He’s a different kind of freedom fighter, one who struggles against the kind of systems that David Douglas fights to create—not that Curse of the Sea Rats troubles itself with addressing this conflict. His darker body hair contrasts obviously with David Douglas’ lighter hair, declaring that he is a formerly-enslaved African even if I am not already familiar with the real-life Bussa who evidently inspires this character. To my reading there’s nothing overtly negative with how David Douglas or Bussa are portrayed, though this is hardly a compliment. It should be difficult to fumble characters like these. It would only be notable if they failed. Succeeding is making par.

It’s Buffalo Calf and Akane Yamakawa who give me more pause. I freely admit I do not have the knowledge or background to delve into how faithfully and sympathetically these characters are portrayed, but I do feel I have enough self-awareness to call out the things that make me feel uncomfortable. If these are well-researched characters based in real history, I do offer my apologies to the developers.

Cheyenne warrior Buffalo Calf’s facial markings have inexplicably survived her transformation into an anthropomorphic rat, her first line of dialog refers to the “warrior’s path,” and after upgrading her abilities she can hurl a tomahawk in battle. Even her name seems too on-the-nose to my ear, but when I compare it to historical Cheyenne figures, it does sound correct. There was even a real Cheyenne figure named Buffalo Calf Road Woman, though her connection to this player character seems tangential at best compared to Bussa.

Akane Yamakawa visually leaves me the most distressed. She’s dressed in a kimono—because how am I meant to know she’s a Japanese warrior if she doesn’t wear a kimono—though thankfully she wields a naginata instead of a samurai sword and speaks perfectly eloquent English. These slight reaches away from stereotypes are undermined by her most notable characteristic: her thin, slanted eyes. They feel pulled straight out of World War 2-era yellow peril propaganda—or from the animation renaissance cartoons that evidently inspire Curse of the Sea Rats.

As though to reinforce that Akane Yamakawa’s racist eye design is not an accident, the party’s benefactor is Wu Yun. He appears from a magical amulet in certain rooms to save the party’s progress and let the player characters upgrade their statistics and abilities. He has more than a passing resemblance to Confucius, questions the party’s competence and openly insults them for their failures—and, of course, also has narrow, slanted eyes. He’s another Asian stereotype, a stern and abusive master lifted straight out of wuxia film dubs.

I found it impossible to play more than a few minutes of Curse of the Sea Rats without feeling bombarded by all these racial tropes encoded into the character designs. Whatever my feelings about the rest of the videogame, I couldn’t leave them unaddressed. I don’t want to assume any deliberate negative action on the developer’s part, so I again offer my apologies if anything is offbase here, but my internal alarms were set off as soon as I saw the character select screen.

The differences between the four player characters are more than cosmetic. When enemies are defeated in combat, they drop spiritual energy that can be exchanged with Wu Yun to increase each character’s statistics and grant them new abilities. These abilities are unique and game-changing to each player character, forging each one into a wholly unique playstyle with distinct advantages.

Bussa can learn to block enemy attacks, which can be further improved to heal him each time he does so. Akane Yamakawa can Focus to increase the damage she deals and has passive abilities that increase her strength when airborne. Buffalo Calf is the stealthy character; she can become invisible and her attacks grow in strength when enemy hit points get low, making her especially powerful against bosses. David Douglas is the most overpowered. He learns to recover health with every basic attack, letting him button-mash through almost every enemy, including bosses, as he recovers far more damage than he ever takes.

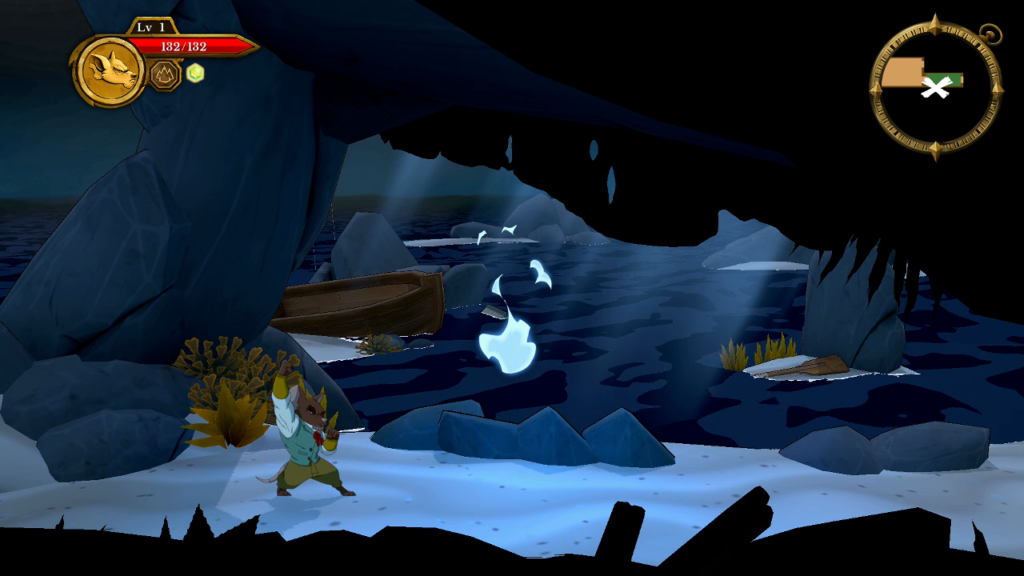

Whichever player character I choose to develop and play as, they follow the same route through the Irish coast in search of Flora Burn. The environment is varied, with the rocky coastline leading into caves, forests, and castle ruins. Graphically, these areas are created from plain, low-poly three-dimensional objects that clash with the traditionally animated player and non-player characters.

Navigating these environments feels familiar. At first, the player characters’ access to the world is limited by their tools and abilities. After defeating a few bosses they learn to double jump and air dash, letting them reach previously-inaccessible platforms and navigate the world with greater mastery. There are also a few locked doors that require plain keys to open, though there are ways around these obstacles if I am willing to explore all the world’s nooks and crannies. This world creates interesting possibilities for speedrunners.

The world is large and dense, sprawling in all directions and creating a satisfying sense of labyrinthian scale. This scale can work against me during sidequests. I encounter many friendly characters around the world who ask the player character to retrieve objects that are hidden throughout the world. I’ll have to find where those objects are hidden myself, which is fair enough, but there are also no marks on the map showing where to return them. I have to rely on my memory to return a macguffin to the correct character. The more of the world I explore, the more troublesome this limitation becomes.

Curse of the Sea Rats’ biggest misstep from a videogame design perspective is its penultimate moment. After scouring the map for every escaped member of Flora Burn’s crew, capping the combat capabilities of multiple player characters, and learning enough movement skills to have complete mastery over the environment, we confront the pirate witch in a cathedral ruin. After her defeat, she absconds back to Blacksmith’s boat with Wu Yun’s amulet. His magic is what allows the fast travel system to work, so we are now forced to walk all the way back to the first area to begin the final confrontation. All the way back from the map’s eastmost point to its westmost.

I’m not being hyperbolic when I describe this as one of the worst design choices I’ve ever seen in a non-linear platformer. The moment just before the final boss should be when the player character is at their most triumphant. There is no enemy they cannot defeat. There is no obstacle they cannot bypass. Curse of the Sea Rats chooses to subvert these norms, making the player characters feel incompetent and feckless when they should feel unstoppable and heroic.

I appreciate an attempt to shake up a genre as familiar and formulaic as the non-linear platformer, but this choice is a bad one. To make the long walk back even more frustrating, new walls have inexplicably appeared to block the most direct route back to Admiral Blacksmith’s ship. The final task before I may put Flora Burn’s evil to rest for good is revisiting a world I thought I knew well remixed into a boring labyrinth that offers nothing new to challenge me except randomly sealed doorways.

If there’s a reason to play Curse of the Sea Rats, it’s for the phenomenal quality of its animation. I am also heartened to see that its map is large and densely interconnected, an area of design in which I feel other indie non-linear platformers of recent years have failed. That is where my positive feelings end. I have great misgivings about the portrayal of several characters, the apparently racist design of the Asian-inspired ones in particular. I appreciate the effort that went into designing four distinct characters, but they all become comically overpowered long before the endgame, particularly David Douglas who is essentially unkillable with his life recovery ability. The only danger to the party in the latter half is a careless jump and a bottomless pit. The penultimate sequence is the worst, adding nothing but padding to a videogame that is already a satisfactory length. Curse of the Sea Rats is wonderful to look at, but not much fun to play.