Potion Permit is a medicinal alchemy and social simulator about operating a small town clinic in a light fantasy world. I play as a young Chemist, freshly graduated from the Medical Association in the capital city, who is assigned to the remote Moonbury Town. They arrive to a frosty reception; Medical Association chemists visited the town once before, leaving behind a decrepit clinic and numerous ecological disasters in the countryside. The residents blame the subsequent fallout on the recalled chemists, and their reaction to the Association’s return ranges from suspicion to outright hostility. It is up to the new Chemist to build trust and friendship with the townies, restore the clinic into a place of healing, and fix the damage to the countryside, all while scavenging for ingredients to use in their medicinal concoctions.

Potion Permit has a strange start. Going in I know that the Chemist’s job is to brew potions that treat the injuries and illnesses that befall Moonbury Town’s residents, but it takes a long time before they are allowed to begin treating patients. After creating my Chemist, who can be a young man or woman with only minor cosmetic differences, they arrive at the train station on the town’s outskirts. There they are met by Mayor Meyer, who takes them to the local tavern to meet the rest of Moonbury Town’s residents. The grim silence the townies greet the Chemist with speaks volumes.

The Chemist is set up in a crumbling shack and encouraged to explore Moonbury Town the next day. Despite its remoteness, it’s a nice place to live. Everyone has at least a room to call their own, and most have their own house. There’s a palatial city hall that does triple duty as a museum and post office. Large shops host a carpenter, a tailor, and a blacksmith. On the coast is a scuttled pirate ship converted into a bait shop and beachside barbecue, and not far from there is the local church. The largest building is the tavern where the townies meet nightly to visit, drink, and play games in the basement arcade. The Chemist makes use of all of these services as they settle into the community.

After a few interminable in-game days where the Chemist is mandated to explore Moonbury Town and its immediate outskirts, they are finally called to the clinic to meet their first patient. The mayor’s daughter, Rue, is sick, and the local witch doctor—that’s not a pejorative, that’s his actual occupation—has been unable to find a cure. It only takes the Chemist a glance to diagnose Rue’s illness and a quick visit to their alchemy pot to brew up a remedy. With Rue cured and Meyer vouching for them, the Chemist earns the reluctant acceptance of Moonbury Town, whose residents begin to visit the clinic for treatment a few mornings every week.

This is where I finally settle into Potion Permit’s routine. The game world operates on an internal clock, ticking away at twenty-four hour intervals. The Chemist wakes up at 6am every morning. My goal is to accomplish as much as I can within the subsequent day using their limited stamina and health pools. The Chemist can replenish these pools by eating a meal prepared in their kitchen or by bathing in the local hot spring, but if either pool empties then they pass out and wake up the next day in their home with penalties to their stats. Playing conservatively is wise.

Several mornings every week, an alarm will blare, signaling that a patient is waiting in the clinic. By speaking with the patient, the Chemist can learn of their complaints, such as a sore throat, stomach ache, or painful joints. Examining the ailing part of their body begins the diagnosis minigame.

The diagnosis minigame takes one of several forms, each built around precision and timing. I might have to play a memory game, studying button inputs and repeating them in succession. In another version, a string of button prompts scrolls across the screen, and I must press each button as it passes through a diamond. In a third, viruses fly across the screen and I must navigate a cursor between them. The more successful I am at completing the minigames, the more satisfied the patient is with my diagnosis.

It is possible to perform so badly at the minigame that the diagnosis will fail and the Chemist will be unable to treat the patient. This negatively impacts their reputation in Moonbury Town, and they will have to regain trust by treating another patient before they can resume using the town’s resources. In the 30+ hours I spend playing Potion Permit to reach the credits, this doesn’t happen to me once. The diagnosis minigames aren’t difficult enough to be a serious threat. On nearly every attempt I get a perfect score.

Once the diagnosis minigame is complete, the Chemist learns what potion to brew to treat the patient’s complaint. This takes them back to the alchemy pot in their house.

Brewing a potion requires me to solve a simple puzzle. Each potion appears on a grid in the alchemy pot screen. When I fill in every highlighted square in the grid, then the potion is successfully brewed and the Chemist can deliver it to their patient.

Filling in the grid is where the process gets interesting. Brewing a potion is like solving a jigsaw puzzle made up of random pieces, with each ingredient I drop into the pot taking a different shape in the grid. Most assume the familiar tetromino shapes from Tetris, turning potion crafting into a spin on that series where I choose which shapes will appear in the puzzle field. There is one important difference: Shapes are static, and cannot be rotated or altered in any way.

When I have found some combination of ingredients that perfectly fills the potion grid, then I have successfully brewed the potion and I can deliver it to the patient. This system allows significant flexibility in which ingredients are used, suggesting the Chemist is a true genius improvising from limited resources, producing the same desired effects from wildly different materials.

Despite their mastery, the Chemist still encounters some obstacles when brewing potions. The primary obstacle is the alchemy pot itself, which can initially only accept five ingredients. Expensive upgrades from the blacksmith expand the number of ingredients that can be used in a potion, and some of these are necessary to craft the more elaborate potions needed later in the story. Ingredients are also further divided into the four elements of Fire, Water, Wind, and Earth. Certain potions refuse one or more of these categories in their creation, allowing for much less flexibility.

Potion brewing is the most interesting activity in Potion Permit and I am sorry to feel that the Chemist doesn’t spend nearly enough time doing it. It’s always performed in response to the needs of a Moonbury Town resident, a rate which ebbs and flows over the videogame’s duration. Despite having much less depth comparatively, far more of my time is spent guiding the Chemist on ingredient-gathering and social-status-building activities.

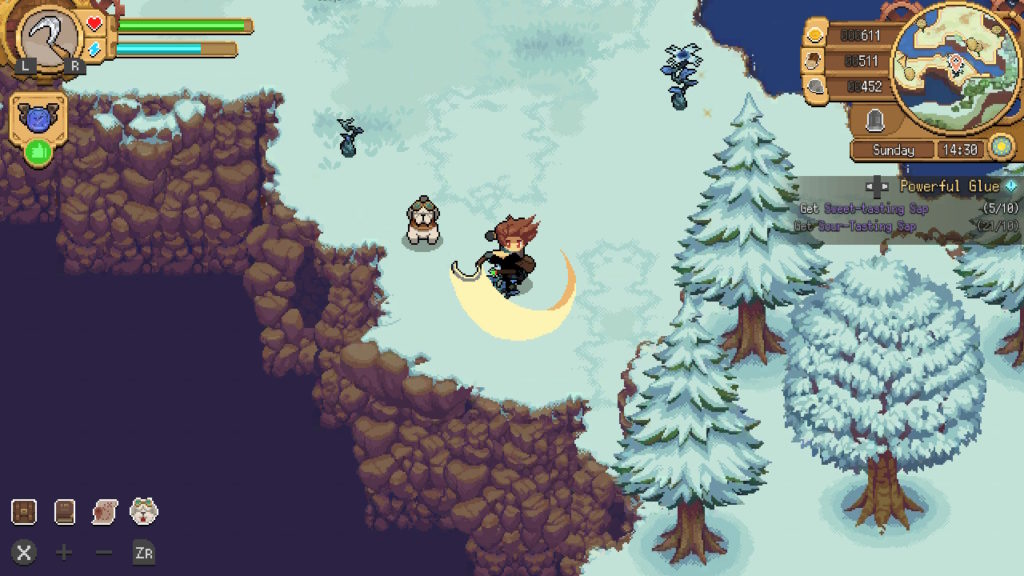

The ingredients the Chemist uses in their potions are all gathered from the wilderness outside Moonbury Town. It consists of three areas which unlock over the course of the story.

There isn’t much to say for the wilderness portion of Potion Permit, despite that I spend more than a third of my playtime there. The Chemist visits almost every day to fill their pockets with alchemy ingredients. Plants can be cut down with a sickle. Trees are cut down by an axe, and rocks smashed into small pieces with a hammer. Trees and rocks also drop lumber and stone resources needed to upgrade the Chemist’s tools, their house, and the clinic.

While they gather these plants and rocks, the Chemist is attacked by wild monsters. There is little depth to this combat. The Chemist can roll away from their attacks, then counterattack using one of their tools. Especially dangerous monster attacks have long and dramatic charging animations, giving me plenty of notice to move the Chemist out of the way. Some monsters are more vulnerable to the hammer or the axe, but against most it barely matters which tool is used. In the first area it’s not even worth the time to dodge monster attacks. They don’t deal enough damage to seriously threaten the Chemist. There is a little more to do in the wilderness than repetitively slash, hack, and crush anything that’s not a floor or wall.

While exploring each area, the Chemist discovers signs of what their predecessors got up to before they were recalled to the capital city. Each of the three areas has been affected by an ecological disaster which is killing the local flora. Investigating these disasters and fixing them—by brewing a potion, of course—forms the story’s main narrative thrust, unlocking new ingredients to brew more complicated potions and creating new paths to other sections of the wilderness. These simple adventure-style mechanics do a serviceable job gating my progress, but they aren’t at all interesting on their own.

Time when the Chemist is not treating patients or gathering ingredients is spent in Moonbury Town developing friendships with its residents. This is where the protracted, alchemy-free introduction is clarified: Despite the many images of potion brewing which festoon Potion Permit’s marketing, and despite the player character’s occupation, and despite the videogame’s own title, the majority of the Chemist’s time in Moonbury Town is spent building the individual friendship meters of thirty-three unique characters.

Building these meters is simple and provides me with plenty of visual feedback. Whenever I speak to a townie for the first time each day, the meter fills a small amount. If I gift them Moon Cloves, an item earned from successfully treating patients, then the meter fills a large amount. This progress is shown by a giant green bar that appears over each character’s head, eliminating the need to dig through submenus to see my progress with any specific character.

At two milestones along each townie’s relationship meter, a short quest is unlocked somewhere in Moonbury Town. These quests are often simple, requiring no more than to visit a specific location at a certain time and watch what happens. These locations and times are conveniently posted on multiple boards around town once they are unlocked. Some quests are more complex, tasking the Chemist with brewing a difficult potion or accumulating a large supply of ingredients then delivering them to the townie. All of them serve the purpose of giving depth and texture to these characters, stripping away their surface readings to reveal the more interesting core underneath.

It’s difficult not to feel Potion Permit is influenced by farm sim-adjacent videogames, particularly in its use of an in-game 24-hour clock, stamina and health meters which can be restored at a hot spring or with prepared food, and social meters built on giving gifts to the many non-player characters. Perhaps this is why I initially feel the cast of Moonbury Town seems a little too inspired by Stardew Valley.

Moonbury Town hosts a single homeless person who it is eventually revealed simply prefers living that way. It has an old man bound to a wheelchair who is angrily bitter about his situation. There are exactly two children living there, one boy and one girl, who are friends seemingly out of proximity more than mutual interest.

These similarities to Stardew Valley ultimately feel more like outliers, homages leftover from an early development period or simply echoes from the videogame design zeitgeist than deliberate plagiarism. The more I peel back the layers of the supporting cast, the more they feel unique.

Since the Chemist visits the hot spring almost daily to recover their stamina and health, they get to know the ladies who work there almost immediately. Cassandra is the police captain’s wife. At first she seems shy and timid, but it’s soon revealed she suffers from severe anxiety which the Chemist can treat with a potion. Olive, who owns the hot spring, seems rather like a stern librarian, but we soon learn that she keeps the place running by herself, including repairing the machines that keep the water clean. Her engineering skills come in handy multiple times in other characters’ storylines. Almost every character in town reveals layers of these kinds as I develop their friendship meters.

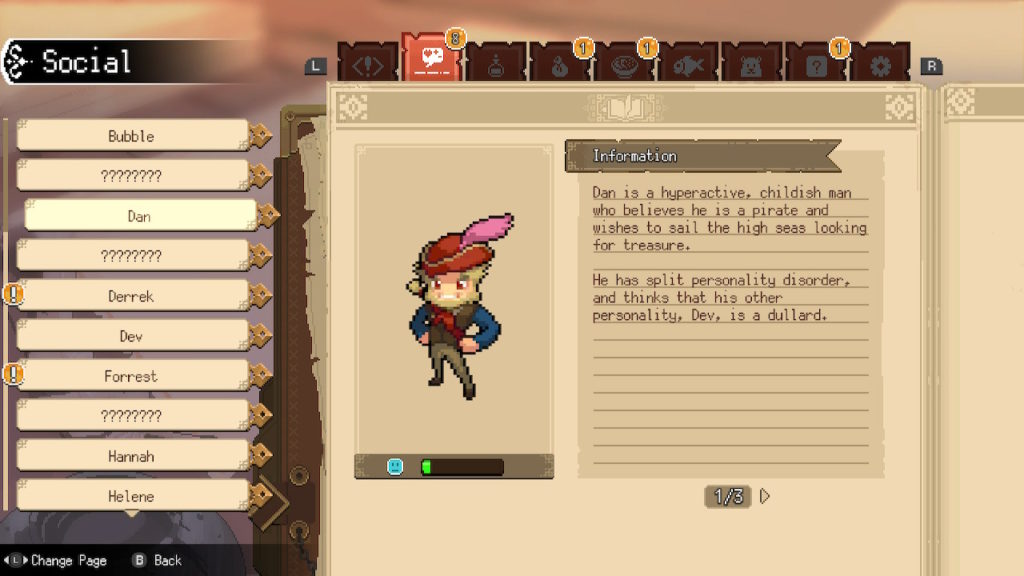

Yet no matter how well I get to know them, a few of these characters do make me uncomfortable. Dev, the town’s reserved postmaster, spends his evenings wandering Moonbury Town as Dan, a loud pirate stereotype. His in-game profile specifically identifies this as a “split personality disorder.” Yikes. Xiao, the mayor’s assistant, is a stereotypically dutiful and efficient man of vague-yet-unmistakable Chinese origin. His house is the one adorned with paper lanterns just in case his name and his personality doesn’t scream “Chinese” in my face loud enough. And does a town this size really need three cops?

There are too many non-player characters crammed into Moonbury Town. There are many that feel like they could be consolidated into other characters, or cut entirely, without affecting the way the town functions. Some of the cast so rarely leaves their houses they may as well not exist. Sociella and Vincent, the nun and graveyard keeper who live in the church, especially suffer from this. The supporting cast’s size grows to such overkill that even the Chemist’s pet dog and the local stray cat have friendship meters to develop.

I especially feel the secondary cast’s size when I reach for the end credits. Healing the damage to the countryside and redeeming the Medical Association is only half of the goals needed to finish the campaign. The other half is capping out the friendship meters of almost everyone in town. Once there is nothing more to do in the wilderness this immediately feels like a tedious grind.

A few NPCs have more than two milestones on their relationship meter. These are the ones it is possible to romance. There isn’t a whole lot more to this aspect of Potion Permit. It’s just a longer relationship meter than non-romanceable NPCs. Thankfully there is no restriction by orientation; the same three men and women are available to Chemists of either sex. Some of the romanceable NPCs include the most interesting people in town, such as Leano the retired pirate captain and even Matheo, the witch doctor whose position in town the Chemist usurps.

Romance in Potion Permit has the same troubling implications it does in other social sims, turning the difficult and rewarding effort of expressing your affection for another person into a purely transactional affair. Love is not found through serendipity and maintained through devotion, it is earned through stalking a designated partner while bombarding them with daily gifts. According to Potion Permit’s interface, it’s literally a lock to be opened.

Not especially enthused by this part of Potion Permit but desirous to see as much of its contents as possible, I eventually settle on Rue, the mayor’s daughter, as a partner. I appreciate her resentment of her parents’ helicopter tendencies and her curiosity about the outside world. After helping her grow rare flowers in her garden, our relationship develops into a romance. Once a day I am able to go on a date with her, which involves shared beachside meals and private, one-on-one visits to the hot spring.

There doesn’t seem to be any point in pursuing romance. Rue doesn’t move into the Chemist’s house following a wedding ceremony. There is no wedding ceremony. The makeup of Moonbury Town is altered not at all by the Chemist growing from a suspect stranger to a trusted and beloved partner. Looking past how Potion Permit gamifies romance into a transactional act of stalking, the feature feels unfinished. There is no discernible reason to do it beyond earning an achievement.

Potion Permit’s best ideas are in its title. Treating patients and brewing potions are when it is most interesting. Sadly, I don’t spend nearly enough time actually doing these things. My playtime is overwhelmed with much more tedious activities like gathering materials in the wilderness and chasing down every single supporting cast member to grind their friendship meter. In short, it’s a good idea for a videogame which is overwhelmed by pacing issues. The things I would rather be doing I don’t spend enough time doing. The things which enable what I would rather be doing take up far too much time. It’s not a bad entry in the indie social sim genre, but I wish it was in totality as good as some of its parts are in their minority.