Cult of the Lamb balances hack-and-slash dungeon crawling with care-and-support community management simulation in a world where cuddly woodland critters dedicate their minds, bodies, and souls to eldritch gods. These critters live in The Old Faith, an ancient forest ruled over by four Bishops who have bound their power-hungry brother, The One Who Waits, in chains connected to their lifeforce. Taking a foothold in four different regions of The Old Faith, each Bishop lives in fear of a prophecy that a Lamb will rise to end their reign and free The One Who Waits. In an attempt to thwart the prophecy, they direct their cults to hunt the lambs into extinction.

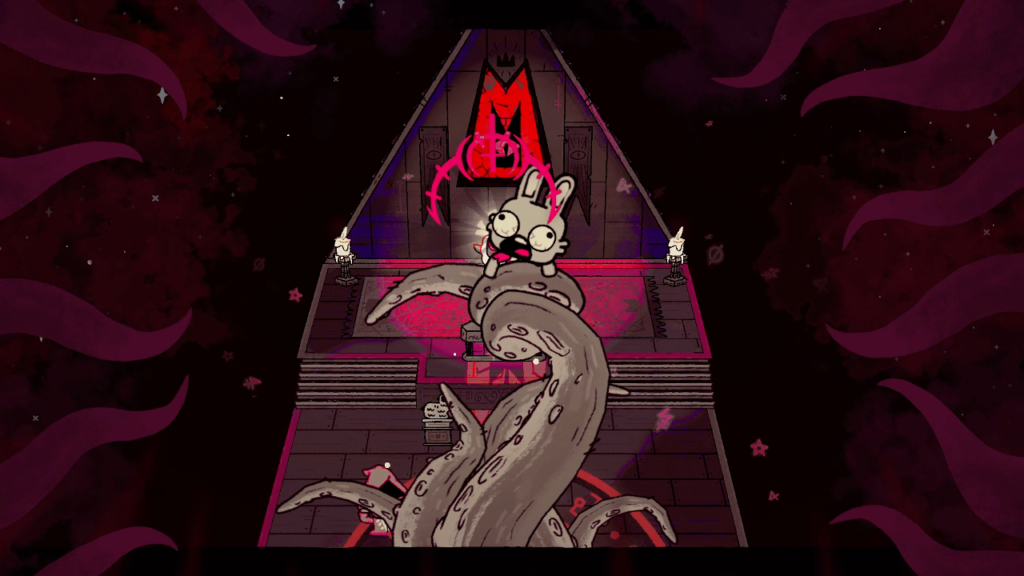

I play as the last living Lamb, who is promptly beheaded in the introductory level. The Bishop’s zeal to exterminate the species proves their folly, as this final Lamb meets The One Who Waits in the underworld, is appointed their herald, and returns to life as a vengeful revenant. Wearing the Red Crown, a dark candle that bestows the Lamb with unholy weapons and curses, they set out to build a new cult that worships The One Who Waits. The power this cult instills in them provides the strength to embark on crusades into the depths of The Old Faith and kill the four Bishops, freeing their master from his prison to unleash terror upon the world.

One thing Cult of the Lamb does well is ensure its dungeon crawling and community management halves work in tandem. There are goals I cannot accomplish in the cult’s settlement without successfully completing crusades, and I cannot complete more difficult crusades without improving the settlement and expanding the cult. This does create some motivational conflict. When on a crusade, I worry about the ever-deteriorating needs of my cultists. When in the settlement I am eager to resume crusading, gathering more of the resources that allow the settlement to expand. The slight difficulty of both is what keeps the pressure to perform well in either half tolerable.

When the Lamb embarks on a crusade, they enter one of four sections of The Old Faith that is occupied by a Bishop and their personal cult. In every crusade’s first room the Lamb is presented with a single weapon and curse to equip. Weapons are straightforward. They work in melee range and have scaling attack speeds. Curses are more varied and function essentially as magic spells, affecting different areas around the Lamb depending on the specific variety.

I find a coming crusade’s difficulty largely depends on which weapon the Lamb is given at its start. Slower weapons deal more damage in a single hit and faster weapons deal less. In theory, faster weapons keep up with the damage output from slower ones by hitting more often. In practice, slower weapons are much safer to wield.

Enemies move and attack in discernible, predictable patterns, encouraging me to run in and strike during windows of vulnerability then dodge away before their next attack. It’s easier to run in with a slow weapon, hit an enemy once, then dodge out to safety than to use a fast weapon to hit an enemy multiple times before dodging. When I am presented with a dagger or claw weapon in the dungeon’s first room, I know for the next few minutes I will have to put the Lamb in more danger just to keep up with a slower weapon’s damage output. There is, sadly, no way to ensure the Lamb will get an axe or hammer, the slowest and therefore strongest weapons, when I begin a new crusade. They are utterly at the cruel whim of the random number generator.

Curses feel less impactful than weapons. Though powerful, each cast drains the Lamb’s fervour, a resource that drops from slain enemies. When the fervour pool empties, I must rely on weapons to refill it. These drops are scarce enough that leaning into Curses as a primary damage source is impossible, particularly against bosses. They’re a valuable source of burst damage, but if I wanted to play as a pseudo-spellcasting Lamb, I would find myself disappointed by the options available.

Completing a crusade tasks me with guiding the Lamb across multiple “floors” of The Old Faith, clearing out a small labyrinth filled with hostile rival cults and ravenous wild animals. After finishing a floor, I can choose from multiple paths on a map. Which path I choose affects the resources the Lamb will find and carry back to the settlement. Some paths give additional wood and stone to build vital structures. Others grant new recruits for the cult. The rest are extra dangerous floors which offer additional powerups, preparing the Lamb for the boss fight at the crusade’s conclusion. If I finish enough individual crusades in a specific wing of The Old Faith, then I can challenge that wing’s Bishop and come one step closer to freeing The One Who Waits.

Few crusades feel especially challenging. Enemy attacks are only threatening if I am being reckless and button-mashy. There is a brief difficulty spike in the water-logged Anchordeep region, a hump that once I work my way over renders the Silk Cradle, the spider-infested final wing, disconcertingly trivial.

The real danger from crusades comes from leaving my cult unmanaged for ten to twenty precious minutes. Time ticks away no matter where I guide the Lamb in The Old Faith, and the cult’s needs persist with it. These needs are faith, health, hunger, and shelter.

Shelter is the easiest need to fulfill. A simple bedroll, built from common materials found during crusades, placed anywhere in the settlement will give a cultist a place to sleep at night. My first resource management test is making sure there is a shelter built for every cultist indoctrinated into the Lamb’s flock. The other three needs require much more proactive effort.

Hunger is the need that requires the most attention, and my ease at fulfilling it is the most noticeable measure of the settlement’s development. One of the first structures the Lamb learns to build is a cooking fire to prepare meals using ingredients found on crusades. Later, the Lamb learns how to build farms that grow small quantities of food. Meals restore meager amounts of hunger to start and may cause negative side effects to the cultists who eat them. It is not until I have opened all four wings of The Old Faith that farms become truly self-sufficient and I can produce the best recipes that confer positive effects instead of negative ones.

Closely related to hunger is health. Cheaper meals may make a cultist sick and need to rest in a shelter for several days, during which time they are not working to generate the settlement’s valuable resources. Cultists who die from illness or starvation can spread disease to other cultists. Ignoring or otherwise being unable to satisfy the cult’s hunger and health needs will lead to the Lamb returning from a crusade to a circle of decaying bodies in the settlement’s center.

The last of the cultist’s needs is faith. It is the simplest to maintain. It drains when other needs are unfulfilled, and a cultist whose faith drops low enough will become a dissenter who spreads discord among the other cultists. Dissenters will abandon the cult after a few in-game days, taking a stack of resources with them. I can deal with them by locking them in a stockade and reeducating them once a day until they are brainwashed into returning to the flock. I can also eliminate them using other, more occult methods of varying subtlety. All my choices have different reactions among the other cultists. Outright murdering a dissenter may eliminate one problem, but it may also cause other cultists to lose faith, snowballing into a serious issue for the Lamb.

The most direct way to keep the flock’s faith topped off is to deliver daily sermons in the temple. This refills a large portion of every cultist’s faith, and when a little extra is needed the Lamb can perform additional rituals using bones looted during crusades. Bones drop in such large quantities the Lamb is never in danger of running out no matter how many rituals are held. They may as well not exist as a resource. As a result, faith is never difficult to keep topped out. The only danger it causes is when it empties completely during an especially long crusade. This circumstance is easily overcome by locking up the resulting dissenters, giving a sermon, and hosting a Bonfire ritual to top out everyone’s faith meters once more

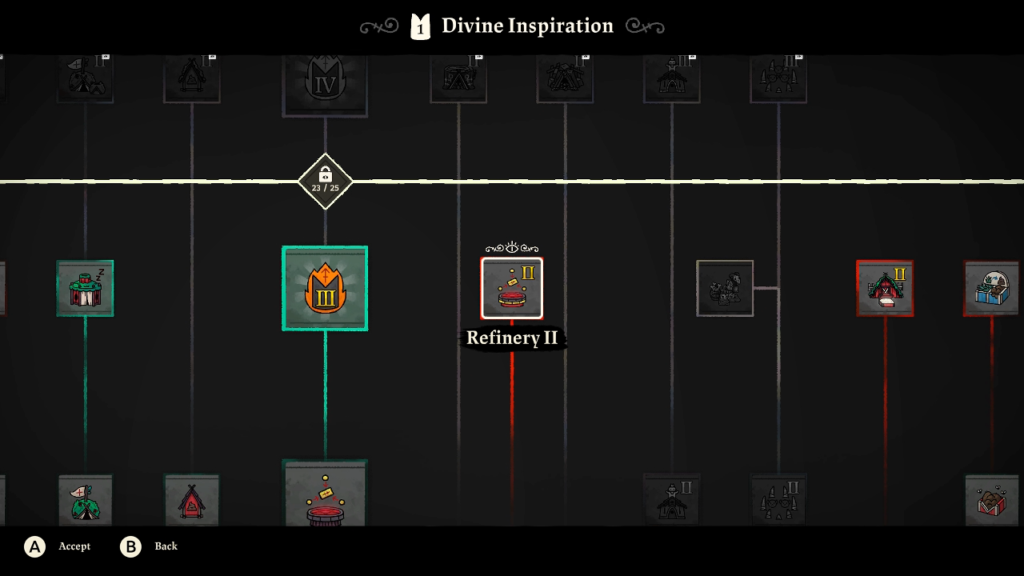

Keeping the cult large and happy is the primary way of improving the settlement. Happy cultists produce Devotion which the Lamb can siphon from an effigy at the settlement’s center. Gathering enough Devotion bestows the Lamb with Divine Inspiration, letting them learn how to build structures like the sleeping rolls, farms, and stockades, but also outhouses where cultists can relieve themselves, janitorial closets so they can clean up their messes, and many other practical installations.

Happy cultists also empower the Lamb during daily sermons given at the temple. Like Devotion, points generated during sermons can be spent to enhance the Lamb’s strength during crusades, giving them access to more powerful weapons and curses. This is the symbiotic relationship between Cult of the Lamb’s two halves at its purest: A larger cult creates a more powerful Lamb, who can conquer more difficult crusades, who can accumulate more resources, which can support a larger cult, which further empowers the Lamb, who can conquer more difficult crusades. It is sadly too easy to reach the Lamb’s maximum power levels; I am still working towards the fourth Bishop when the Lamb suddenly has no room to grow any further.

While the Lamb is in the settlement, they may be approached by a cultist with a personal quest they want fulfilled. Often, these quests are relatively simple, such as making a specific meal or performing a specific ritual. Others are more frustrating, especially those that send the Lamb into The Old Faith to gather certain kinds of food. Food drops are random and can take several crusades to gather enough to satisfy the cultist. The randomness at finding requested drops is frustrating, but the arbitrary time limits placed on these quests can make them infuriating. Multiple times I fail a cultist’s quest because the needed items refuse to drop within the time limit, resulting in the quest giver losing faith in the Lamb and having to spend time in a stockade to be re-indoctrinated.

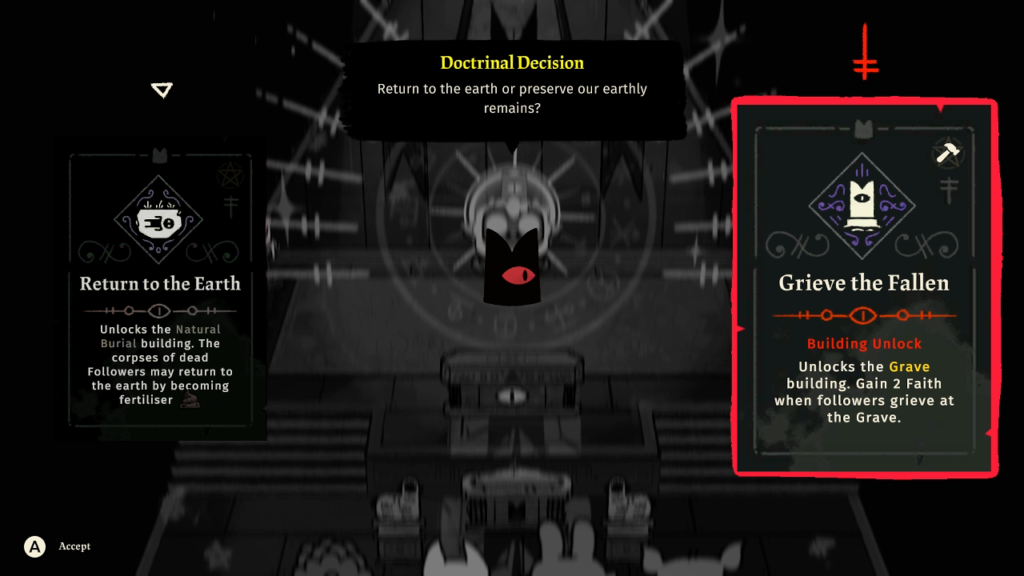

Cultists with requests can be ignored without affecting their faith, but ignoring them also deprives the Lamb of the most reliable source of commandment stones. Given as rewards for completing quests, commandment stones allow the Lamb to declare new doctrines for the cult to follow. These doctrines are where Cult of the Lamb’s real customization choices lie.

Doctrines come in multiple themed categories and are mutually exclusive; the Lamb can learn to declare a Ritual Fast that stops cultists’ hunger meters from draining for several days, or a Feasting Ritual that refills all cultists’ hunger meters and restores more of their faith. One option kicks the hunger problem down the road for a few days, buying some time to come up with a long-term solution. The other eliminates the hunger problem immediately, but also allows it to begin draining again immediately. Which is preferable is up to me, but I cannot choose both.

Which doctrines I choose really determines what kind of cult the Lamb ends up leading. There is no doubt that they worship an evil demon no matter what doctrines are declared, but there’s still some room to slide between soft-selling evil and embracing cartoonish evil. One doctrine makes cultists more appreciative of a “meal” made from grass, the cheapest and least-filling food available at the cooking fire. Its counterpart makes the cult into cannibals, and it’s up to the Lamb to choose who will be the meat. Another doctrine lets the Lamb pit two cultists against each other in combat to the death, which is one of many options that can be exploited to eliminate a dissenter. Its counterpart lets the Lamb marry their cultists—and yes, polygamy is not only possible, but often incentivized.

Doctrines are where Cult of the Lamb offers most of its real customization, and the best reason to replay is to see how a cult with different doctrines handles the various community management situations.

I find that neither of Cult of the Lamb’s halves fully satisfies my appreciation for dungeon crawling or community management activities. Neither is difficult. Crusading offers little variety, with the same strategies applying in every wing no matter what randomized weapon and curse the Lamb discovers on their way to the next Bishop. Managing the settlement has more complexity and customization, but the basic structures are more than enough to keep everyone happy so there’s little reason to dip into some of the more specialized options—it has breadth, but not depth. If there’s a venn diagram of the two genres, I do find myself in the overlapping section. When I look to either side, I see community management fans unswayed by the dungeon crawling, and I see dungeon crawling fans unconvinced by the community management.

The simplicity of both halves may be to prevent alienating fans of the opposing genre experiencing hack-and-slash action or management simulation for the first time. As a fan of both, I find myself satisfied, yet also disappointed.

By the time all four Bishops are killed and The One Who Waits is freed, there isn’t much left for me to do. I can continue to build the cult, but there isn’t anything to keep reaching towards. There are a large number of cosmetic structures I can build that heavily theme my settlement, ranging from spooky webs to eldritch deep-sea visages to vibrant flowers that recall the eerie atmosphere of Midsommar. Since my settlement otherwise remains stagnant and the cult doesn’t care about the settlement’s aesthetics, this feels like a self-induced chore. The main menu includes a “roadmap” of future content updates, but at the time of this writing that roadmap is blank. Only a handful of sidequests might offer anything to keep my attention, but these are also easily completed before I reach the final Bishop.

Once I’ve freed The One Who Waits there simply isn’t anything to do, and there seems to be nothing forthcoming to remedy that aside from a literally empty promise.

Though I feel let down by Cult of the Lamb’s genre-mishmash, I am also drawn to its theming. The unexpected pairing of woodland creatures in an Animal Crossing-esque township with blood sacrifices, unholy rituals, and evil gods is a potentially interesting one. Unfortunately I never feel like this portrayal is anything more than skin deep; I never feel like it’s saying anything. The world is filled with upside-down crosses, doctrines inscribed on tablets, and a messianic Lamb embarking on bloody crusades against Other religions, invoking a deliberately counter-Christian ideal. The aesthetic seems inspired by the worst imaginings of the Satanic Panic, a wave of paranoia that swept—and continues to sweep—the United States claiming a hidden Satan-worshiping cabal is enslaving and slaughtering children.

There’s nothing to Cult of the Lamb’s portrayal of these fears other than what it is. It seems to say, “wouldn’t it be funny if adorable animals committed evil acts in the name of Cthulhu?” And it is funny, for a few hours. Then it stops, leaving only the tenuous connection to real-life fears, as though the only cult images it can conjure are from the fevered imaginings of the religiously paranoid.

As a bloody imagining of a doomsday cult, Cult of the Lamb isn’t even that creative.

Cult of the Lamb’s conceit of dungeon crawling balanced against community management simulation is a great idea whose aspirations are let down by execution. Its dungeon crawling half never rises above fair. Its community management half also never rises above fair. One of these halves might have gotten away with being merely passable if its counterpart were amazing, but neither rises to its occasion. Its sum is unable to be greater than its parts, dooming it to being merely fair. I hoped macabre themes might elevate it beyond its design mediocrity, but even here I am disappointed. It has the appearance of edginess from a distance, but upon closer inspection its corners are worn and its center hollow. Cult of the Lamb is a hollow chocolate effigy: Satisfactory, but empty and leaving me wishing for more.