This review contains images with words and subject matter some may find upsetting.

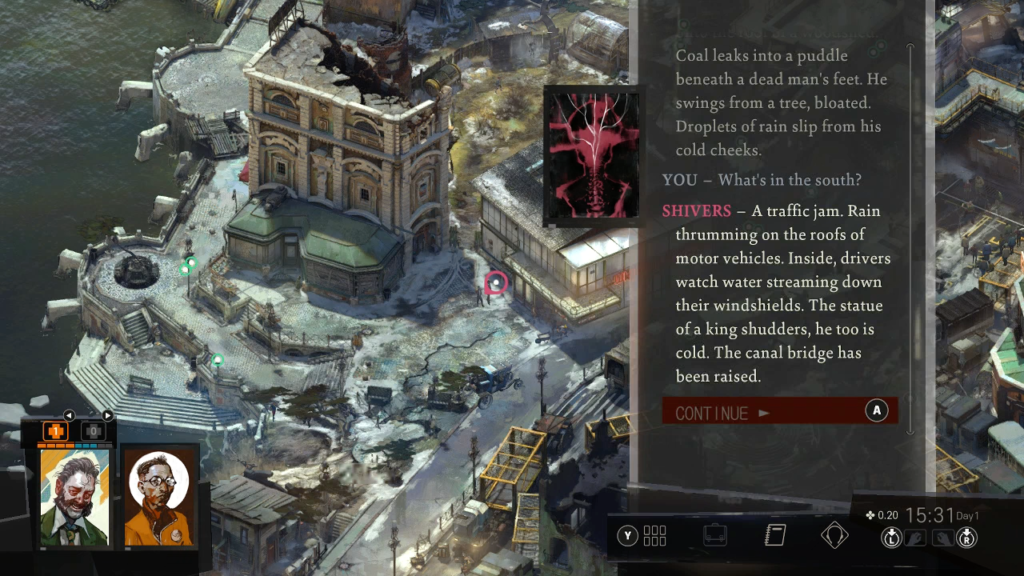

Disco Elysium is a narratively-driven adventure RPG about detectives investigating a murder in a harbor district fraught with sex, violence, and poverty. It kicks off when the player character wakes up in a destroyed hostel bedroom suffering from a hangover so severe it has obliterated his memories and identity. Dressing himself with the only clothes he can find—a garish Disco suit, complete with flared collar, bell-bottoms, and heeled boots—he wanders out into the hostel proper. There he meets Kim Kitsuragi, his new partner, who assures him that he is the detective assigned to the case. Together they step out into the yard where the victim’s body hangs from a tree in an apparent lynching. It is up to me to pick up the pieces of this shattered man and solve a murder which is even more complicated than it first appears.

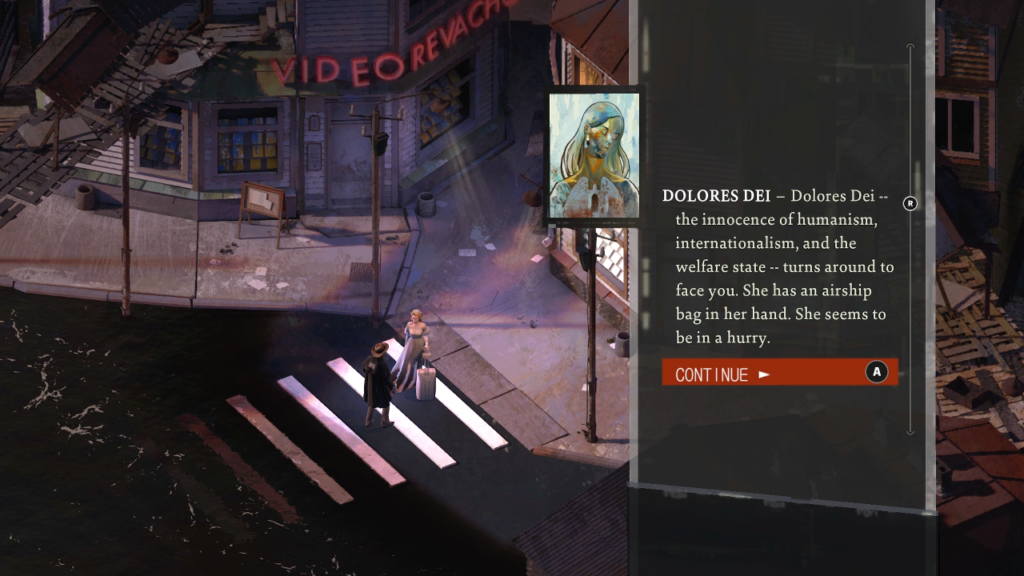

The term “roleplaying game” brings to mind wizards and warriors fighting tyrants and monsters in a fantasy world, their combat performance determined by statistics and the whims of rolled dice. Disco Elysium is not this kind of RPG. It only resembles one, particularly the so-called “PC RPGs” where I explore and fight monsters on a pre-rendered backdrop and character interactions are narrated in a large text box. The pre-rendered backdrop is here, but there are no monsters to fight and the text box steps up to full-time duty for interacting with the world.

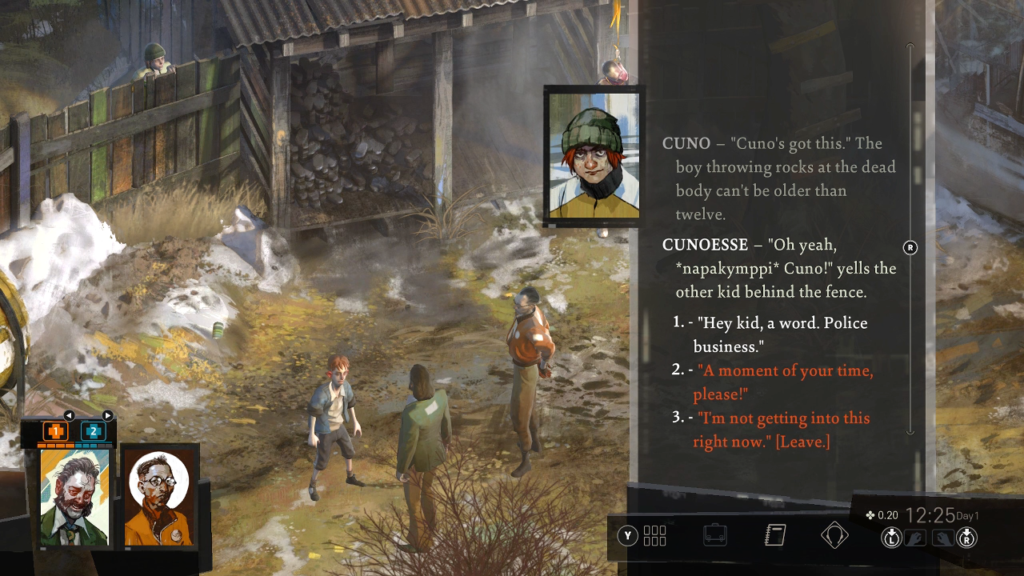

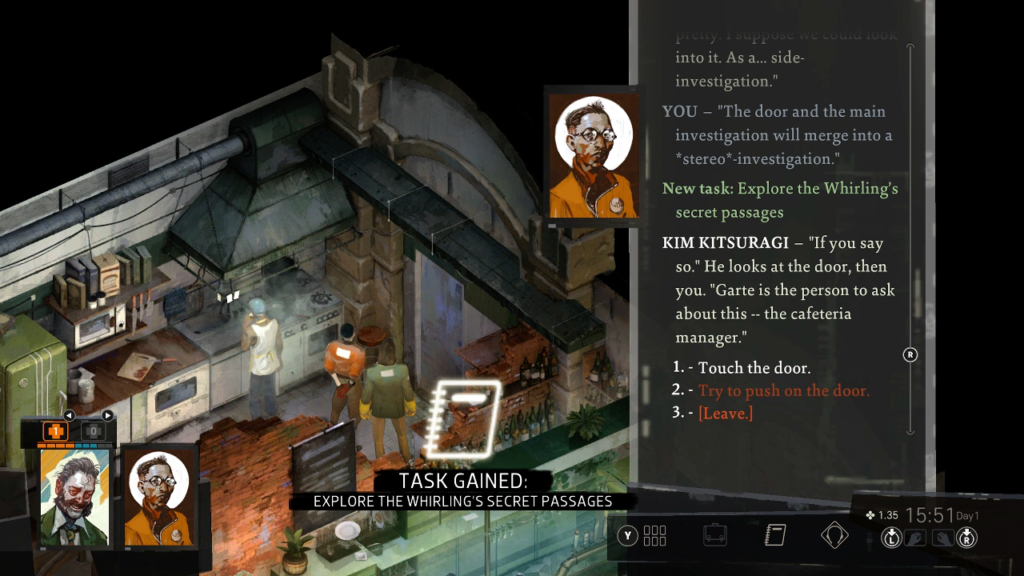

The increased prevalence of the text box makes Disco Elysium closer to a classic point-and-click adventure than an RPG. During my investigation, I can have conversations with dozens of non-player characters and examine many more objects. The choices I make during these interactions determine the flow of my investigation. Learning a new detail about the murder or uncovering a contradiction to something I was told previously can open up new dialog choices with characters or even open up entirely new areas.

Despite its adventure videogame trappings, Disco Elysium eschews the most infamous design trope from that genre: symbolic keys and keyholes. Not once do I encounter a roadblock where I wander the world showing everything in the player character’s pockets to every NPC and object, hoping something new will happen. Though there are some moments where flashing a detective’s badge or a chipped yellow mug will get results, most of my progress happens because of logical narrative steps found in conversation and confrontation. Which steps I can make and how successful they are is determined by how I distribute the player character’s statistics.

When I begin a new game, I can choose one of three archetypes the amnesiac player character can embody. These archetypes roughly align with three different RPG classes, automatically distributing statistics to determine which skills the player character excels at. The Thinker archetype is “extremely intelligent” but “bad with people.” The Sensitive archetype has a “magnetic personality” but “might begin to lose his mind.” The Physical archetype “interacts with the world through his body” but is “dumb as a rock.”

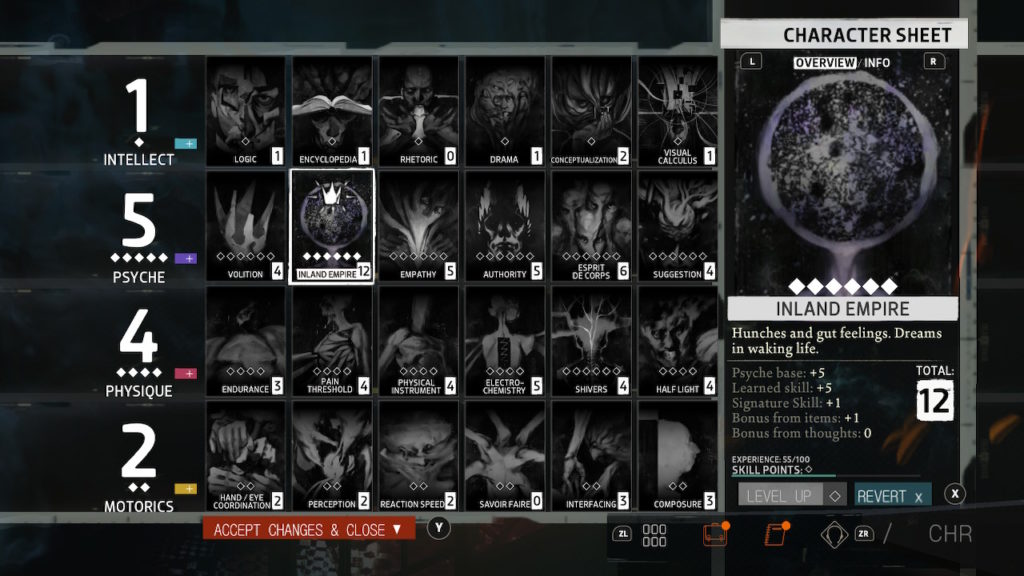

In keeping with how Disco Elysium isn’t that kind of RPG, these stats aren’t quite like anything seen elsewhere. A Thinker archetype specializes in stats like Encyclopedia, which represents their knowledge of the world’s many historical and cultural artifacts, and Visual Calculus, which lets them mentally recreate crime scenes at a glance, Sherlock Holmes-style. A Sensitive begins with strong Empathy and Esprit de Corps, affecting how well they understand the perspectives of suspects and fellow cops respectively. A Physical starts out with high Endurance and Pain Threshold stats, letting them suffer through difficult bodily confrontations the other archetypes may struggle with.

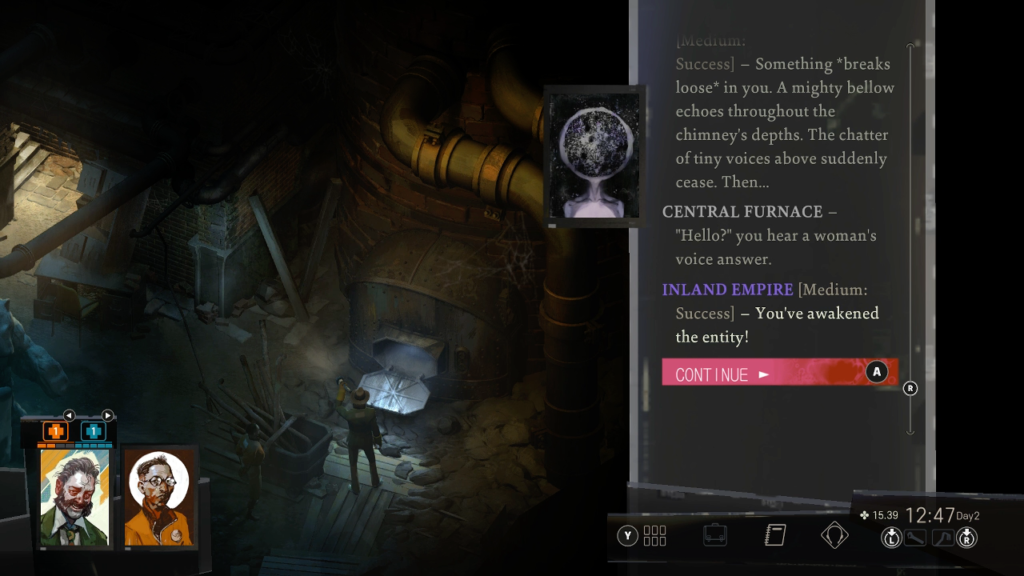

What makes these stats even more unique among RPGs is each functions as an individual character with a unique voice, personality, and motivations. The higher I develop a particular stat, the more dominant that trait’s voice becomes during the unfolding narrative. If multiple stats are built high enough, they become a cacophony of voices vying for attention within the player character’s internal dialog.

Stats that complement each other, like Authority and Suggestion, will build off each other and support their conclusions. Stats that are at odds, like Physical Instrument, which wants to solve problems with brute force like a schoolyard bully, and Logic, which wants to solve problems through intellect and understanding, will argue with and attempt to override each other.

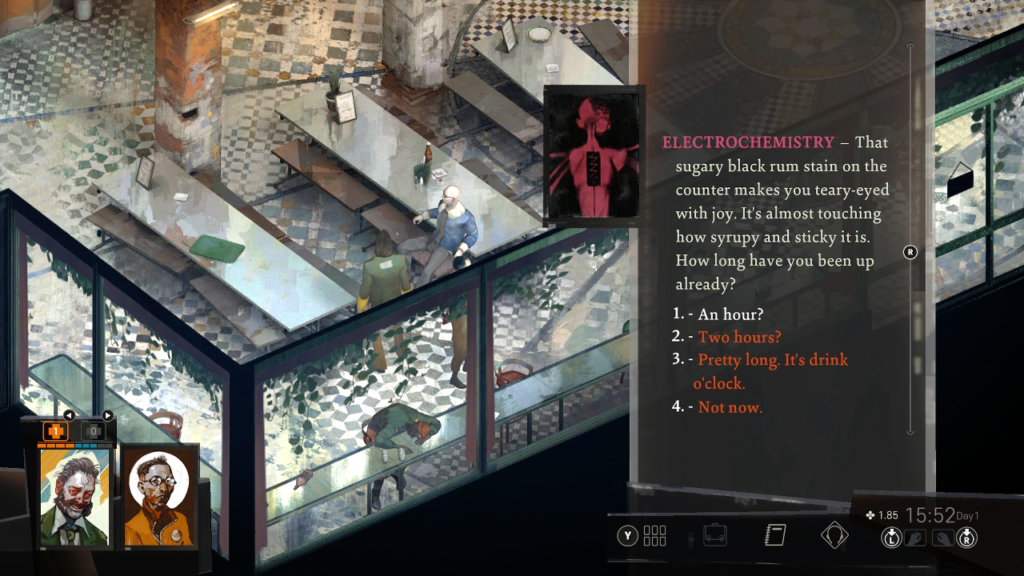

While having some points invested in a stat can be useful, too many points become too much of a good thing. Electrochemistry gives the player character deep knowledge of drugs and the useful ability to understand and relate with Disco Elysium’s drug users, but also saddles the player character with a drug addiction himself. Building this stat too high will literally add quests to buy alcohol and cigarettes or steal narcotics to the player character’s quest log. A high Authority stat fills the player character’s internal dialog with authoritarian rants and resents NPCs who disrespect the player character. A high Inland Empire stat bombards the player character with incidental details drawn from the environment, many of them useless.

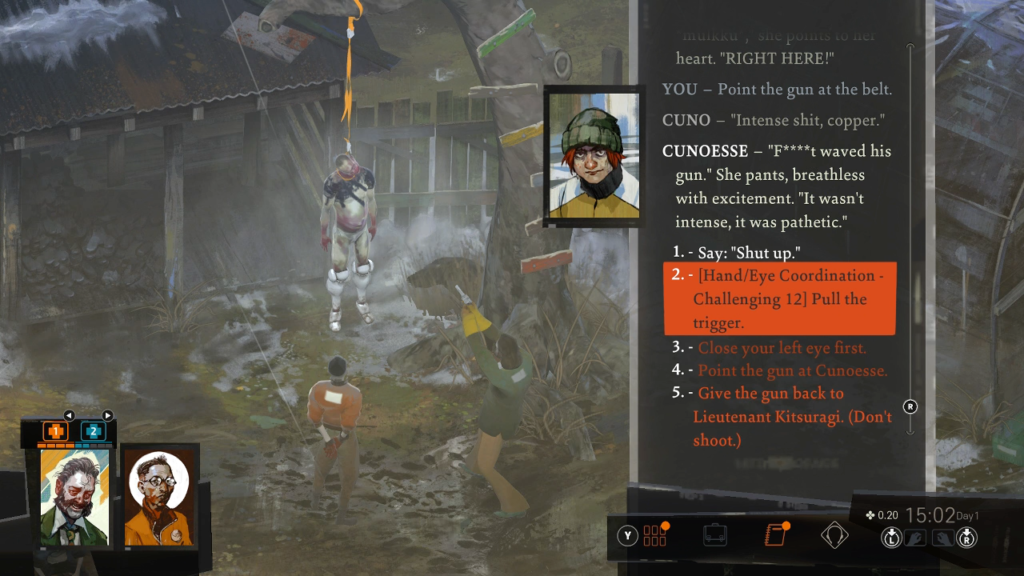

The consequences for too-high-stats may seem easily avoided by simply not sinking too many points in them, but Disco Elysium has an interesting way of making these investments difficult to avoid: skill checks.

Many of the choices I want to make when interacting with Disco Elysium’s world are governed by skill checks. When the player character regains consciousness in the opening moments, my first task is to dress his naked body in the clothes strewn around the room. This is simple enough for the shoes, pants, shirt, and jacket, which are thrown across the floor and furniture. The necktie dangling from the ceiling fan proves more difficult. To get it down, I must pass a skill check whose success percentage is determined by the player character’s Savoir Faire stat. The more points invested in Savoir Faire, the more likely I am to successfully pull the tie down and return it to the player character’s neck.

Failing the skill check isn’t the end of the necktie. If I invest a point in Savoir Faire upon leveling up, the failed skill check will unlock and I can return to try again with an improved chance at success. Since experience points are constantly doled out for doing just about anything, I have regular opportunities to improve the stats that let me pass desired skill checks. Making repeated investments in a stat to pass a difficult skill check is the main way Disco Elysium pressures me into building one high enough that it becomes a dominant part of the player character’s collective personality.

Many of Disco Elysium’s most difficult skill checks have improbably low success rates when I first encounter them. Learning that a character is lying, pleasing them in another conversation thread, or completing distant, seemingly unrelated tasks can pile on multiple passive bonuses that make passing the skill check much more likely. I can also improve my chances by wearing certain clothes, smoking a cigarette, or drinking alcohol before the attempt. Especially thorough investigation of the world and its characters gives unexpected rewards of greater success rates in the most difficult skill checks.

While pursuing the central murder investigation, I will inevitably run out of ways to move forward. The inscrutable femme fatale on the hostel’s second floor will deflect all my questions. The gang of union thugs will close ranks and refuse to talk, aided by their savvy lawyer. I have invested all of my levels up into improving the player character’s stats, yet the skill checks that move the story forward remain stubbornly closed. Showing that Disco Elysium is an RPG, after a fashion, I need to gain more experience levels if I want to continue in the main quest. This is when it’s time to pursue the many sidequests.

The world overflows with additional investigations and “investigations” that feed the player character’s bottomless hunger for experience points. Next door to the hostel is a shopping center whose single tenant thinks the rest of the building is haunted. I can aid a cryptozoologist in his hunt for the Insulindian Phasmid. I can help found a nightclub that specializes in anodic dance music. In a subplot that feels inspired by The Hangover, I can track down all of the player character’s lost police equipment. And then there’s a little matter of the two millimeter-wide hole in reality.

All of these sidequests are as intricately designed as the core murder investigation, and some even tie into that plot in surprising ways. Completing them is technically optional, but also provides greater insight into Disco Elysium’s world. More importantly, they pump up the player character’s experience levels to make those difficult skill checks in the main plot easier to pass.

I go into my first time playing Disco Elysium well aware of its reputation for weirdness, and wanting to maximize how unusual my experience will be, I opt to play as a Sensitive archetype. Beginning with high Inland Empire and Electrochemistry stats, within minutes of emerging from the player character’s hostel room I have had a conversation with the necktie and obtained a sidequest to buy a pack of cigarettes. I begin the preliminary murder investigation and speak to everyone I encounter, putting every level up into Inland Empire. With every point, that voice becomes louder and louder until it chimes in at nearly every opportunity. I am delighted, confident that I can sidestep troublesome skill checks through meticulous exploration of the world.

I am mistaken.

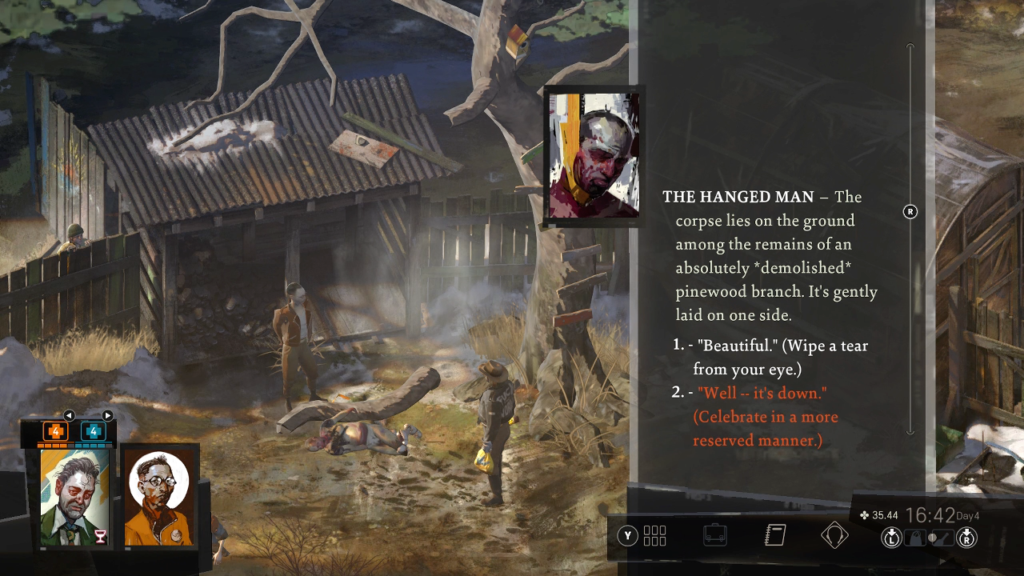

One of the first tasks I am given is to get the victim’s body down from the tree it hangs from. There are many routes which will accomplish this, but not ones which accommodate every kind of detective. When my attempts to remove the body with only Kim’s help prove disastrous, he suggests asking the local union leader for help in getting it down.

The gate into the harbor where this leader resides is guarded by a phrenology-spouting brute named Measurehead. To get past him I must either defeat him in a fight with a high physical skill check, which my player character is ill-equipped to do, or internalize and repeat his racist worldviews, another difficult skill check which might have consequences down the line with other, less bigoted characters.

I let the matter drop and begin exploring the rest of the neighborhood, believing I will inevitably find another, unexpected route into the harbor. All the while I pump every level up I can into Inland Empire and the player character’s other impractical, eccentric “emotional” stats.

Over twenty hours later, I complete every sidequest I can discover. My map is littered with skill checks which my detective, uninterested in developing his physical or mental skills, has been unable to pass. It looks more and more like I have locked myself out of any way forward. At the edge of quitting in frustration, I squeeze one more level up out of the world and put it into Perception, finally letting me into a hidden door I can clearly see but the player character, being as unperceptive as a rock, cannot. The door finally opens and suddenly every wall in my way falls away. From there it is smooth sailing to the ending, which is admittedly another fifteen hours away.

Is it possible if I wander around the neighborhood long enough that Disco Elysium takes pity on me and opens the harbor without passing specific and arbitrary skill checks? I’d believe it, but I don’t want to waste twenty-five or more hours waiting for that to happen. It is dispiriting to spend almost a full real-time day trying to complete one of the first goals I am given. To make it more frustrating, the wound is self-inflicted; a single point in Perception early on saves me twenty hours of growing despair.

The lesson I learn is, unless I want Disco Elysium’s central murder to be especially aggravating to solve, I must save levels up for skill checks I need to pass instead of stats I think are interesting. I want to believe that any kind of detective can find a way to solve the murder and see the ending, but this seems to not be the case. There are multiple points where only certain stats will allow the story to progress regardless of how many sidequests I complete.

No matter how much I aspire to build the player character into a spacey cop with borderline-psychic abilities, I am railroaded into forging him in specific ways at a few key bottlenecks. It’s equal parts frustrating and disappointing that Disco Elysium treats me and the player character this way.

My admiration for the intricacy and abundance of skill checks is at odds with the frustration a few of them instill. This cognitive dissonance encapsulates my feelings about many other features in Disco Elysium as well, especially its setting.

The murder investigation takes me all over the region of Martinaise, a trading hub whose volatile history has left its people impoverished in spite of the thriving harbor at their center. Many of the characters I speak with have their own viewpoint on how Martinaise came to its current state. A lorry driver near the harbor gates blames the whole situation on foreigners, uttering racist dogwhistles at Kim and goading me into joining in. Evrart Claire, the union head, mixes socialist ideology with crime boss tactics; part of interacting with him is deciding for myself whether he is more the former or the latter. Across from the hostel, an aging imperialist war veteran plays a ball-tossing game with his more moderate companion. Each character is complicated. Even the openly despicable ones have nuance and layers to their bigotry.

These character’s layers are aided by the sheer length of interactions with them, though these lengths can begin to feel excessive. Many conversations, filled with richly-detailed lore and well-written dialog performed by a talented voice acting cast, can take upwards of a half-hour to plow through. These long segments of talking become still-longer as I develop the player character’s stats and multiple aspects of his personality begin chiming in at every conceivable opportunity. It’s a prodigious amount of writing and an incredible number of flags and triggers happening behind the digital curtain to make it all work, but the result is an impossibly dense amount of text that makes War and Peace seem like light afternoon reading. Playing Disco Elysium for more than a few hours at a time can feel overwhelming.

Visually, conversations are accompanied by characters standing motionless in a static environment. The stillness makes Disco Elysium frequently uninteresting to look at. This doubtless contributes to the many times my eyes droop and my consciousness recedes into the white noise of near-sleep as voices drone on and on and on. After a few seconds of silence I burst back into awareness and select the next conversation prompt, hoping against hope that I haven’t dozed through something important.

I cannot conclude without writing about Kim Kitsuragi. In the near-forty hours it takes me to finish Disco Elysium, not once do I resent his companionship. He’s an effective foil for a blank slate protagonist like the player character, possessing a distinct but subtle personality.

Kim takes a contented back seat to the investigation. He offers quiet advice about how to proceed in conversations and interrogations, only intervening when I’ve let things get out of control. He tries to hide his silent awe at my inexplicable successes and reserved amusement with my comical blunders. He disapproves of my Electrochemistry-induced drug habit but doesn’t say anything about it. He does protest my search for the Insulindian Phasmid, but tags along for the hunt anyway. He puts up with most of my antics with a kind of bemused stoicism, so I know I’ve really screwed up when he confronts me directly with anger in his voice. When I make a huge discovery by passing a skill check with an especially low percentage through sheer luck, his sincere and pointed statement of “Great work, detective,” is the most memorable moment of the entire videogame.

Kim is one of the most likable NPCS I’ve ever encountered in a videogame and nothing tempts me for a replay more than to simply spend more time with him as another, more competent version of the player character. Perhaps it is not my frustration with the murder investigation’s progress which finally spurs me to invest that single, desperate point into Perception. Perhaps it is my sense of Kim’s mounting impatience that breaks me. I feel like I needed to quit screwing around with some kids blasting anodic dance music and finally buckle down with my partner, a modest, soft-spoken, and honorable man for whom I feel enormous respect.

Disco Elysium is intricate, dense, and often genius. It is also slow, unfocused, and sometimes boring. I went in steering myself into the weirdness I had read so much about, but this path soon mired me in frustration and resentment. There are innumerable ways to traverse the intersecting investigatory threads, and yet still not enough to accommodate every kind of detective I may build with its unorthodox RPG systems. Only my connection with Kim Kitsuragi, hero cop, keeps me committed. I simply can’t bring myself to let the man down. Disco Elysium is certainly a memorable experience, even if all those memories are not positive ones for me.