The Wild at Heart is a non-linear adventure about two lost children who explore a mysterious forest filled with puzzles, treasure, and a lurking evil. Wake and Kirby are young friends who decide to run away from their unhappy homes through the forest bordering their backyards. After wandering for hours they find themselves in the Deep Woods, a magical land where lost people from across history are trapped forever while their memories are devoured by a hidden creature called The Never. Only by teaming up with Spritelings, diminutive spirits of nature native to the Deep Woods, can Wake and Kirby discover The Never’s prison beneath the trees and defeat it before their memories are lost forever.

In order to escape the Deep Woods, I must apply the unique tools and skills possessed by Wake, Kirby, and their Spriteling partners to solve puzzles, bypass obstacles, and open new paths through the forest.

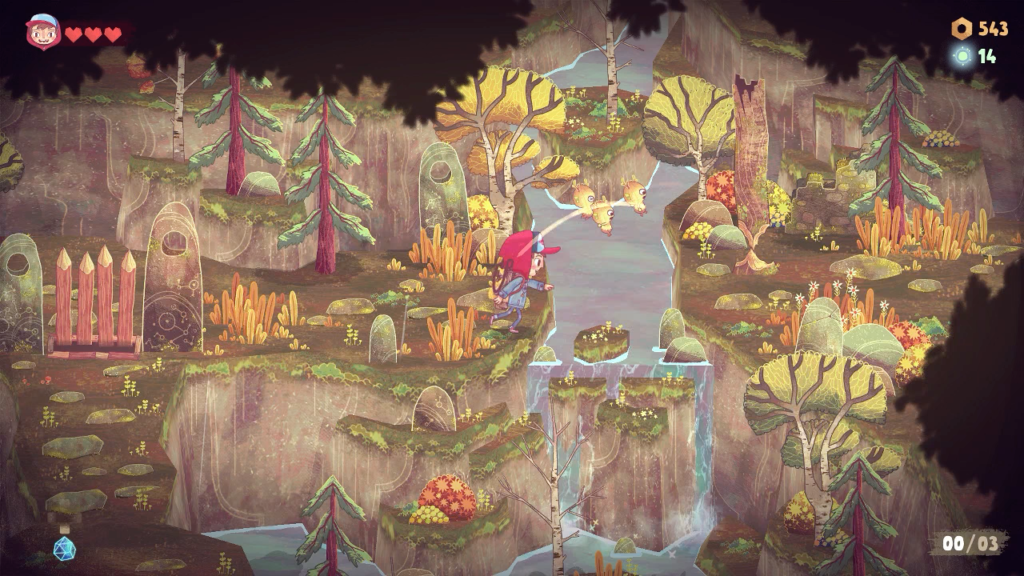

Wake is a budding engineer who has created a Gust Buster, a souped-up vacuum cleaner that can suck in items and Spritelings and blow away small enemies and piles of leaves or garbage. Kirby’s small size lets her squeeze through tunnels Wake cannot, an advantage which leads her to a lantern that can activate many of the ancient magical objects scattered around the Deep Woods. When needed, the pair may split up to solve alternating door puzzles, or travel together for safety.

In addition to their unique skills, Wake and Kirby need the help of the Spritelings. A herd of up to sixty made from five varieties follow the player characters. Some Spriteling varieties are obvious, like Emberlings and Shiverlings which are immune to fire and ice respectively. Others are more creative. Barblings are fragile but the sharp thorns on their head are deadly weapons against the Deep Woods’ monsters and also lets them stick to objects. Lunalings can interact with the same magical objects as Kirby’s lantern and their strength increases by a factor of three in moonlight.

Wake and Kirby need the Spriteling’s help to solve the puzzles they lack the strength or numbers to complete on their own. When Spritelings are tossed near a fragile earthen wall, they begin breaking it down. When tossed near a pile of sticks, they build a bridge across a nearby river. Many objects needed to progress through the plot are too large to be carried in the player characters’ pockets, instead requiring dozens of Spritelings to work together to carry them back to The Grove, the one place in the Deep Woods protected from The Never’s influence.

Wake and Kirby will require several hundred Spritelings to complete their quest, so they are forced into the near-constant chore of gathering the materials to create more. Hatching a Spriteling of any variety requires a corresponding seed, or “Pip,” and a magical essence called Glint. Both are gathered from giant squashes that grow throughout the forest and regrow every in-game day.

Replenishing and expanding the Spriteling herd necessitates large numbers of Pips and Glints, bogging down the adventure with microbreaks to smash open every squash Wake and Kirby pass. These are often the same squashes they already smashed a few minutes ago during the previous in-game day. Smashing the same few squashes over and over while trying to accomplish more substantive tasks becomes repetitive quickly.

Despite these small, consistent efforts to build a Spriteling reserve, at multiple points the momentum is brought to a complete halt to grind out more of a specific variety after a particularly catastrophic mission wipes out most of the herd. This is aggravating, especially since it’s usually a direct result of The Wild at Heart’s weakest aspect: its combat.

The Deep Woods is home to many supernatural creatures who will attack Wake and Kirby during their quest, including corrosive slimes, giant frogs, and anthropomorphic mushrooms wielding primitive weapons. Like assigning Spritelings to a task, they can be directed to attack a monster by tossing them near one. There is some level of strategy involved—Emberlings are immune to the elemental powers of fire-enhanced monsters, for example—but combat mostly consists of tossing every available Spriteling at a problem until it dies.

This isn’t to say that combat is either brainless or effortless. Wake and Kirby have limited health meters, and if they take too many hits from monsters they will pass out and wake up at the nearest campsite the next in-game morning. It’s all too easy to lose track of where a monster is attacking in a herd of swarming Spritelings, often leading to cheap shots against the player characters.

Spriteling intelligence and tools to precisely control their movement are limited, so they sometimes become trapped in a cycle of hurting against the more powerful enemies. This sees them wiped out even with a significant advantage in numbers. The result of most fights is the herd either demolishes their target or gets demolished by it with little in-between. Even the deadliest monsters respawn every few in-game days, so the Spriteling herd is constantly at the whim of the combat’s capricious outcomes.

The good news is The Wild at Heart’s shallow combat can be mostly ignored. There are two difficulties, “Wanderer” and “Adventurer.” Wanderer trivializes the monster encounters so I can focus on the engaging and interesting exploration and puzzle solving instead of the dull and frustrating combat. The only reason to play on Adventurer is vanity and ego.

What I have described so far may sound like Nintendo’s Pikmin videogames. The comparison is valid. A lost traveler, stranded in an alien world in search of escape, enlists the help of tiny creatures to solve puzzles and defeat giant monsters through sheer weight of numbers. This comparison is shallow. The reality of playing The Wild at Heart is quite different from Pikmin.

First and foremost, Pikmin is a time management videogame while The Wild at Heart is a more straightforward logic puzzle one. In both videogames I will direct Pikmin or Spritelings to break down a wall or turn a pile of sticks into a bridge. In Pikmin, I need to commit dozens of Pikmin and several minutes of the remaining time limit to finish a job. In The Wild at Heart, these tasks are finished in seconds by a handful of Spritelings and there’s little reason to account for how soon nighttime and its deadly predators may arrive.

The Wild at Heart also has prominent crafting mechanics. At times it even feels like a Survival videogame on the Adventurer difficulty. Aside from gathering Pips and Glint to create new Spritelings, Wake and Kirby also stumble upon scrap metal and loose parts which can be used to upgrade their tools and health meters, or turned into gadgets that can stun enemies and destroy obstacles. The Deep Woods is also abundant with fruit, mushrooms, and delicious monster parts which can be cooked into life-restoring meals.

Lastly, The Wild at Heart deviates from Pikmin by consisting of a single, interconnected world. Wake and Kirby are given general directions on where their next goals may be accomplished, but the order they complete these goals and the paths they take getting there is up to me. Sometimes there are choices in the order goals may be completed. At other times a goal cannot be completed until I discover an upgrade or new Spriteling elsewhere in the Deep Woods.

As an open world videogame, The Wild at Heart features many sidequests dispensed by members of the Greenshield Order, humans who live in The Grove at the Deep Woods’ center. Kirby and Wake can scour the world to find lost cats, recover artifacts for a private museum collection, and complete monster bounties. All these sidequests only provide crafting materials (and achievements), so they can be ignored or completed at my preference without seriously impacting campaign progress—which is good, because the bounty hunting missions are a grind and a bore.

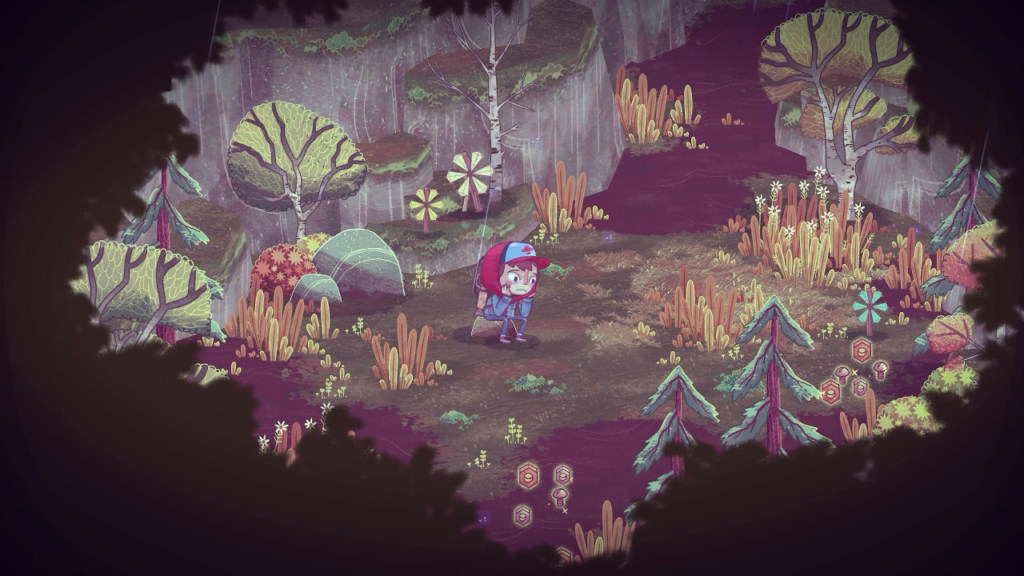

The Wild at Heart also stands apart from Pikmin with its art design and setting. The art design used to create the world and characters reminds me most of illustrations by children’s author Maurice Sendak. Surfaces are decorated with a blend of slightly differing colors, similar to a gradient, filling the world with rich contrasting tones that feel both mysterious and welcoming.

The other humans Wake and Kirby encounter in The Grove have distinct, recognizable, and whimsical designs. Scrap Heap, who becomes an engineering mentor to Wake, wears a teapot with a lit candle on its lid for a helmet. Grey Coat knows more than anybody else about Spritelings and wears a massive patched brown coat (he lost his grey one). Crow’s Nest, who runs the shop, is dressed as a plague doctor, suggesting the many centuries he has spent in the Deep Woods, and is fully aware he has a magpie roosting on his hat instead of a crow, thank you very much.

The themes presented by these storybook images are much more sad than a typical children’s book. Both Wake and Kirby have difficult home lives with their parents and guardians. Each time they sleep at one of the Deep Woods’ many campfires, they have dreams about these troubled relationships—memories which are being swallowed by The Never. These dreams suggest a complicated dynamic which The Wild at Heart sadly never fully examines: The children either have to remember and deal with their troubled family lives, or else become like Scrap Heap, Grey Coat, or Crow’s Nest, their identities consumed by The Never until they forget even their own names.

The melancholic story contrasted with the rich, vibrant images recalls Sendak’s Where The Wild Things Are, another story about a boy who runs away into the woods, finds what he was looking for in the form of friendly forest creatures, but comes to regret taking his former life for granted.

The Wild at Heart is richly imagined and beautifully created, but it never quite fills me with total satisfaction in anything it tries to do. The sight of fifty-plus tiny Spritelings following the two player characters is delightful, but the requirements to produce them quickly begins to feel like a chore. The puzzles that block access to other parts of the Deep Woods are interesting, requiring a bit of thought and maybe an undiscovered tool but never leaving me stuck for solutions. These are contrasted with the respawning monsters which are never interesting to fight and take longer and longer to defeat the closer the heroes come to The Never’s prison. The art design is beautiful, but the story never fully capitalizes on its themes of familial relationship and memory loss. It works best as a variation on Pikmin infused with indie spirit, more focused on microcosmic puzzles than macrocosmic time management skills. It’s a fine and engaging adventure that lacks refinement.