Tails of Iron is a brutal melee combat videogame about a young king fighting to rebuild his kingdom after it is destroyed by an old enemy. I play as Redgi, the youngest and smallest son of the king who succeeds his father over his older, larger brothers through trial by combat. Just as he is about to accept the crown, the Crimson Keep is attacked by an army led by a bloodthirsty warchief. With his father dead and the keep and nearby village razed, Redgi begins his reign at war. Only by rebuilding his kingdom and rallying his people can he hope to defeat the warchief’s army and avenge his father.

What makes the situation a little different from other videogames about medieval warfare is King Redgi and his people are rats, Warchief Green Wart and his putrid army are frogs, and the unfolding conflict is narrated like a storybook by Doug Cockle in the full voice of his most famous role. Tails of Iron feels like playing an especially gruesome passage from Brian Jacques’ Redwall novel series if it was read as a bedtime story by Geralt of Rivia. It’s not easy and it’s not pleasant, but it is a lot of fun.

Rebuilding Redgi’s kingdom requires me to traverse three mid-sized regions spread across three individual maps (plus a fourth that only contains the final boss fights, no exploration required). I begin in the ruins of the Crimson Keep, and later discover the caves and tunnels beneath it. I also visit Long Tail Village and its outskirts, and visit the caves and sewers beneath them. Then there’s a third, more unusual place Redgi discovers which sits atop another warren of caves and tunnels. Each location feels visually distinct but geographically there is little difference in navigating them.

My progress across these regions is sometimes impeded by obstacles that require specific tools to overcome. Wooden barricades cannot be passed until Redgi is equipped with a heavy weapon which can smash them. Some tunnels are filled with poison gas which steadily drain Redgi’s life until I find special equipment to help him breathe. Still others are locked by simple keys.

These are the trappings of a traditional non-linear platformer, along the lines of Metroid or Hollow Knight, but trappings is all they are. Redgi’s journey is plot-driven; if the narration doesn’t describe him going to a place, there’s no reason to go there yet. If I venture unprompted into new territory, all I will discover is an empty room still waiting for its event flags to be triggered by plot progression.

There are a few secret rooms containing hidden goodies, but they require little cunning to discover. Their outlines appear on the map, their entrances are plainly visible when I walk by them, and there’s always some point in the story where I will pass through their vicinity.

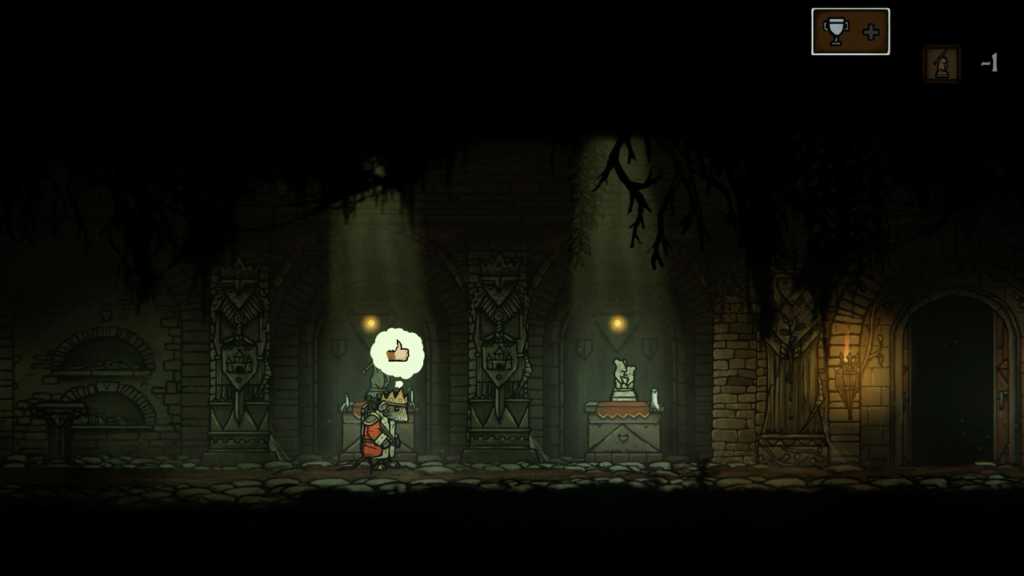

When Redgi sits on his throne, his brothers and advisers will give advice on what should be rebuilt next. These projects take lots of gold, which is earned—how else—by visiting a quest board in each town hub to accept missions. Each mission invariably sends Redgi into the depths of the local map to kill an especially large and dangerous frog, bug, or mozi (mosquito).

Frustratingly, these quests may only be accepted one at a time, even though many of them send Redgi to spaces only a few rooms away from each other. It’s exasperating to accept a quest, walk to the other end of the map to complete it, then walk back to turn it in, only for the next quest to send Redgi straight back to where he was to complete the next one. Their redeeming quirk is they appear in batches and the maps are so small that these many expeditions take almost no time at all.

These quest board missions have the appearance of sidequests, but do not function like ones. They are the only way to earn the gold needed to progress the story forward, usually providing exactly the amount needed for the next milestone if I complete all of them. It’s not until late in the story that I have a gold surplus and can skip a few missions if I want. If I do complete them, there’s nothing special to spend the extra gold on. Some quests are even repeatable, for reduced reward, for no discernible purpose.

In addition to gold needed to rebuild the Keep and Village, I can also spend iron bars and bug fragments on quest-related items and new equipment from several shops. They drop in such large quantities that not once do I have to worry about Redgi’s pockets turning out empty. I always have enough of these additional currencies to buy anything I need—and everything I don’t. They may as well not exist.

So far I may have made Tails of Iron sound small and repetitive. These are legitimate criticisms I have of its level and scenario design, but I wish to emphasize that I do not feel they detract from my ultimate enjoyment. My narrated tour through a small, uncomplicated world signposted by redundant quests is made resplendent through Tails of Iron’s intricate and challenging combat systems.

Redgi is a proactive warrior-king, a royal who gets what he needs by going out and getting it himself, usually through murderous conquest. When the Crimson Keep is sacked by Green Wart’s army, Redgi personally kills most of the invaders while pointing the few survivors to safety. When he receives intel about where Green Wart has taken his captured brothers, Redgi sets out alone to rescue them. When insects infest the sewer, Redgi climbs down the well with sword and shield to clear out the swarm. In this way he’s a highly irresponsible king, but it is excellent for putting me in situations to fight a surprising variety of enemies.

Combat is slow and methodical while still requiring razor-sharp timing. Enemies share common visual cues which tell me how to react to the coming attack. Jagged yellow lines emanating from an enemy means their next attack will be fast but weak, and I can parry it with a swing from Redgi’s shield to send them off balance. This leaves them vulnerable to several damaging weapon blows. Bold red lines mean I must slide past a powerful lunging attack with a single press of the dodge button, and if I’m quick, I can turn and hit their backsides with Redgi’s weapon. Thick pink circles means a crushing blow with a wide area of effect is coming and I need to roll Redgi to safety with two presses of the dodge button.

It’s not as simple as reacting to visual prompts. As I progress through the story, enemy attacks not only become more powerful, punishing my mistakes with larger chunks of Redgi’s health bar, but their attack patterns also become faster and longer. In Redgi’s trial by combat for his father’s crown, his hulking brother Denis attacks with single telegraphed strikes with long pauses before he acts again, leaving me plenty of time to get in a few hits. In the ultimate showdown with Redgi’s fated foe, Green Wart makes several attacks using multiple patterns with no pauses in between. Practically the only chance I get to hurt this ultimate enemy is when I counter his yellow attacks. Every other move I make is pure survival.

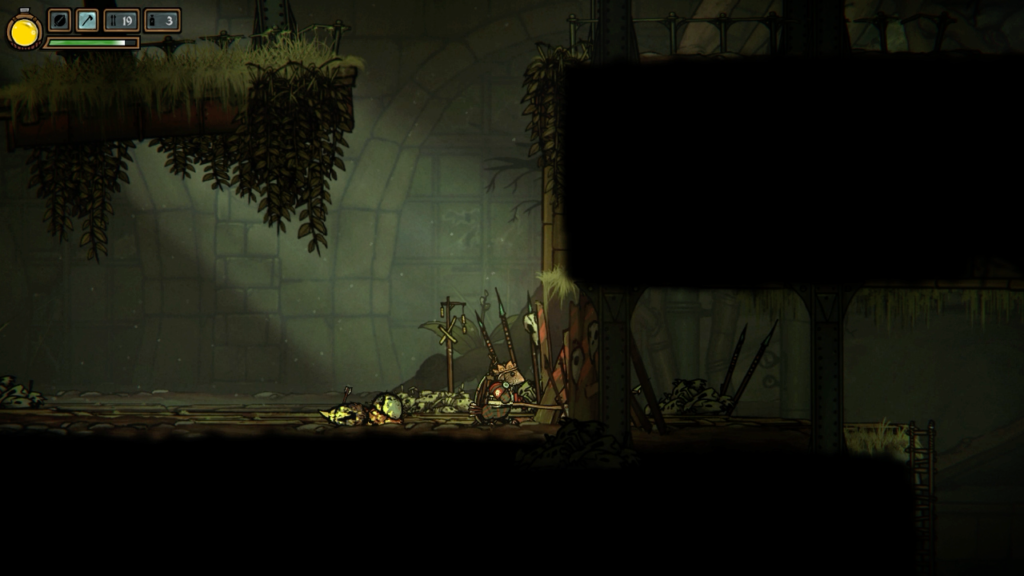

I cannot overstate how brutal these duels become. Don’t let the mouse-like appearance of the rat protagonists lull you into a false sense of security. Redgi emerges from most fights covered in the bodily fluids of the enemies he just hacked into pieces. Most opponents have unique death animations where Redgi crushes their sternum, stabs them in the forehead, or disembowels them. Its Teen rating from the ESRB is a fascinating window into a culture that finds sexuality more objectionable than graphic violence.

Whether Redgi crushes, impales, or disembowels his enemies depends on the weapon I equip him with. There are a few health upgrades to discover, but the vast majority of the items I find while fighting across the kingdom are new weapons and armor pieces. There are dozens in total to be found. Each weapon has different ranges, speed, and power, and each piece of armor offers different levels of protections against different types of enemies. The most important attribute that all equipment shares is their weight. A more damaging sword will probably weigh more than a weaker one, while heavier armor will offer more protection than lighter armor. The heavier the equipment I use, the slower Redgi will move.

The dozens of weapons and armor allow for an array of customizable options. While it is tempting to pile the heaviest armor on Redgi to give him the most protection, I find it more practical to accept lower protection to keep him at the lowest weight rating. Taking less damage when Redgi gets hit is nice, but taking no damage at all because I’m able to dodge enemy attacks is even better. It’s still nice that there are options available for players who prefer to be an impenetrable wall instead of a speeding dart.

If the emphasis on highly-customizable melee combat and its bloody results don’t make it clear, Tails of Iron is not aimed at a casual audience. There is a “Fairy Tail Mode” difficulty for players who only want to enjoy the story, but I am skeptical that this will be a rewarding experience for them. Tails of Iron’s story frankly isn’t interesting enough to be “enjoyed” on its own merits. The default “Tails of Iron Mode” and the intimidating “Bloody Whisker Mode” are aimed more at players looking for a challenge, and it will satisfy them handily.

Tails of Iron is an imperfect videogame. Its world and the goals within it are meandering and redundant. The story is serviceable for shuttling King Redgi from set piece to set piece, but offers few surprises and even less to ponder. It’s a videogame concerned with one thing, and it’s fortunate that it does that one thing with masterful execution: Combat. With a highly customizable player character and simple mechanics built on reacting to clear visual prompts, it’s incredibly satisfying mastering the ever-complicating duels that find Redgi rebuilding his kingdom and striking back at his people’s enemy. If you’ve ever enjoyed the rush of squeaking out victory against a challenging boss who was decimating you just fifteen minutes ago, Tails of Iron should be put high on your wishlist.