It’s a lovely day in the village. A gardener tends to his vegetables, his neat rows of carrots, cabbages, and pumpkins separated from the nearby public park by a low brick wall. A boy amuses himself with a football and a toy airplane in the street near the village’s only phone box. Across from him, a market has sprung up in the middle of the street, the woman running it unconcerned by the non-existent traffic. She keeps a stern eye on the bits and bobs she has laid out for sale on crates and folding tables. Neighbors relax in their yards divided by an adjoining fence; one yard is tidy and tastefully decorated, the other chaotic and filled with tacky knick-knacks, yet the pair share a content indifference to their neighbor’s presence. Pub patrons sit on a patio, basking in the sunlight with their drinks while the owners busy themselves preparing for the evening rush.

I am a horrible goose. Yet not an especially unusual goose. My primary tool for mischief is grabbing things with my beak, waddling away with a pilfered prize with its owner in exasperated pursuit. I can also flap my wings and let out a fearsome “honk!” to those who would challenge me, but these abilities are mostly for show. What I lack in exaggerated player character aptitude I make up for with spiteful mischief. Using my mighty goose skills, I make it my mission to ruin the village’s peaceful atmosphere.

Because it’s a lovely day in the village, and I am a horrible goose.

My day begins in my goose home at the center of the village park. After completing some rudimentary tasks which introduce me to my goose powers, I swim across the pond and find myself outside the gardener’s vegetable patch.

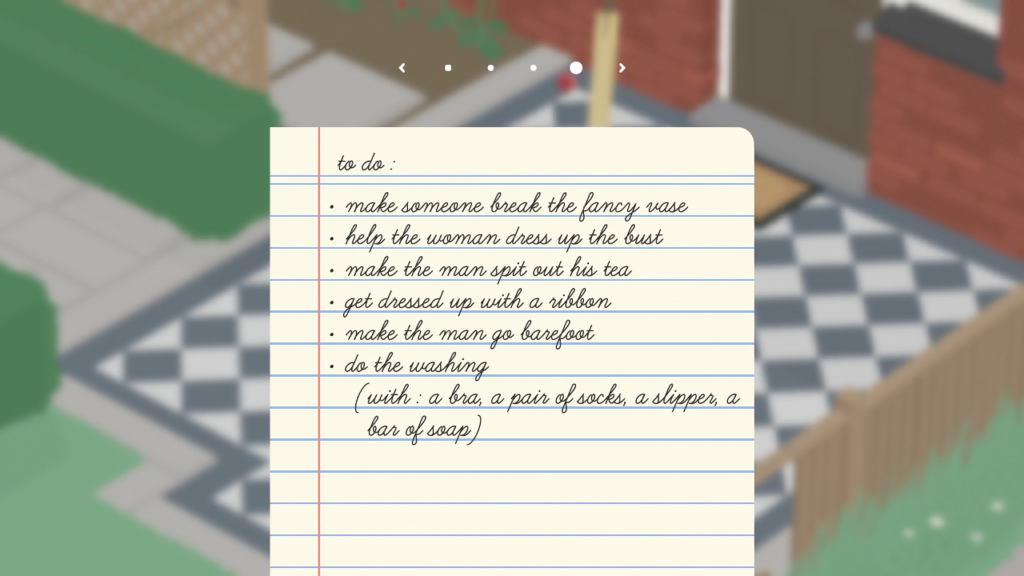

Here I am prompted to open my notepad to view the checklist of awful things I will accomplish today—every horrible goose carries a notepad like this, quit asking ridiculous questions. My goals here include “get the gardener wet” and “rake in the lake.” But before I can do any of these things, I must complete the first task: “Get into the garden.”

The garden wall only comes up to a person’s waist, but it’s high enough to stop my stubby goose legs from climbing over it. Near the gate I see the gardener has left a portable radio on top of some cement bags. I pick up the radio with my bill, which turns on. The gardener comes to take the radio away from me, forgetting to close the gate again when he returns to work. Now with free access to the vegetable patch I can find all sorts of ways to be a horrible goose to the hapless gardener.

My day proceeds like this through each of the village’s four small sections. I explore the environment to find some weakness I can exploit to access the villagers’ personal space, then I make their lives as miserable as I can. The boy playing with his toys is terrified of me, so I honk at him until he seals himself inside the telephone box. The tidy man kicks his legs in the air while sipping his tea or reading his newspaper, so I snatch his slippers from his feet and drop them in his fountain. The man who owns the pub chases me when I snatch his tomatoes, so I drop a bucket on his head to express my displeasure. All of these tasks and many more are dutifully listed in my goose notepad.

Why do I do these things? Because I’m a horrible goose. What more reason do I need.

Not all of the tasks listed in my notebook make sense to me. In all four areas I visit I am tasked with picking out certain items and dragging them to a specific location. In the street market, I have to fill a shopping basket with a toothbrush, toilet paper, and some cleaning supplies. Annoying the villagers makes sense to me—I am a horrible goose, it’s what I do—but how does filling a basket with random items create annoyance? These goals feel like someone trying to fill my day with more things to do even if they aren’t rewarding and don’t make sense.

I feel justified in ruining the pleasant days the villagers enjoy because nothing really punishes me for my horrible goose behavior. No matter how many experimental approaches it takes before I finally snatch the gardener’s hat from his head, he never uses his dangerous tools against me. He only chases me away before returning to his chores with an annoyed huff.

The closest thing to consequences I experience are the “No Gooses” signs which are soon erected by the villagers. I know when I see one that it is time to move on to the next area where there are more villagers to annoy. A horrible goose’s work is never done.

My antics are underscored by a whimsical freestyling piano track that disrupts the village’s pastoral ambience. When I waddle between destinations, I hear only the blowing of the wind and the clatter of people opening and closing doors as they go about their self-important lives. But when I snatch the messy woman’s laundry from her clothesline and go tearing across her yard with her dashing at my heels, the piano track bursts to life with comic perfection. It slows to a few light tinkles as the woman catches me and reclaims her unmentionables, then recedes back into silence as she stalks away to hang her laundry back up. At least, until I steal them again.

Surely the world approves of my actions if it gives me my own light-hearted backing track.

The capers I impose upon the unsuspecting village only take about two hours. The village is surely bigger than the four small areas I visit, but I am just one bird. When my day’s work is completed I receive a new checklist with more goals, but they send me back to the same places. There’s nothing new to see, just new ways to annoy the same villagers.

Do I wish I could unleash my mischief on the unseen parts of the village? Maybe. If I could, would I feel that my checklist goals begin to feel redundant? Would I feel that I had run out of ideas and I was continuing to pile on just to reach an arbitrary page number in my notebook? That is certainly possible. Do I feel like my current stopping point is satisfactory, and my desire for more is part of the perfectly balanced allure of being a horrible goose? Absolutely.

As a horrible goose I am biased, but spending my day disrupting the serene mundanity of a lovely village feels like undiluted genius. I could choose to spend my time experiencing epic stories, challenging myself with cerebral conundrums and paradoxes, or just filling time with good old-fashioned mayhem, explosions, and violence. But there’s something more appealing and amusing about the inscrutable vendettas of petty waterfowl in sleepy townships. I can hardly wait to do it all over again tomorrow, because it will be another lovely day in the village, and some part of me will always remain a horrible goose.