This is a review of a psychological horror videogame. It contains images and descriptions of blood, dismembered bodies, character designs reminiscent of the Ku Klux Klan, and other elements some may find upsetting. Please be aware of this content before reading.

Dusk is a horrific first-person shooter that recalls the genre’s 1990s PC heyday, particularly id Software’s Quake. I play as a man who awakens in the basement of a house in Dusk, a small town in a non-specific area of the rural United States that has been taken over by an otherworldly cult. I fight past the house’s monstrous inhabitants, adding a variety of guns to the player character’s arsenal along the way. These cultists will be the first of hundreds that fall before me in violent and merciless fashion on my way to defeating the darkness at the heart of Dusk.

There is little narration and even less exposition in Dusk. What I learn about the town’s history and what transformed it into a hellscape ruled by a bloodthirsty cult is communicated through implication and level design.

I discern even less about the player character. He doesn’t have a name. What brought him to Dusk and how he ended up in that basement is told in a graphic novel which is not included with every purchase. What motivates him to penetrate the cult’s heart and put it down, instead of using his skill and weaponry to escape to safety, goes unexamined.

These details are not what Dusk deems important. It focuses on tense level design, horrific enemies, and fluid first-person movement. It focuses on them to incredible results.

Dusk uses a retro aesthetic where the world is presented using a low number of polygons. Flat surfaces and sharp angles abound not only in the many environments, but also on all the monsters who stalk it. The textures that decorate these surfaces are likewise low in resolution. Even the words I find on walls scrawled in blood that hint at the backstory have charmingly pixelated edges.

This low-poly approach serves many clever functions at once. First, it is reverential, resembling the similarly low-poly monsters that populate Quake, a clear influence on Dusk’s design. Second, it is practical, helping Dusk to run at an exhilarating sixty frames per second on all kinds of platforms, even the humble Nintendo Switch.

The low-poly aesthetic’s third and smartest effect is to enhance the horror. The odd proportions and crude joints created from building creatures out of a few squares and triangles makes them seem like mockeries of a human shape. Quite apart from looking cheap, their stiff joints and frozen necks suggest that whatever has afflicted Dusk’s populace corrupted them on a physical level.

It’s too easy to accuse Dusk of merely copying Quake’s visual style. It’s a clear and deliberate choice with many practical effects on the final result.

Another place where Dusk feels like Quake is movement. The player character moves fast and jumps far, skills he needs to keep ahead of his enemies. They will try to swarm the player character with sheer numbers, pin them in enclosed spaces, or bombard them with slow-moving projectiles coming from all directions. Dusk revels in the 1990s first-person shooting ethos of “if you’re standing still, you’re dead,” and it has the responsive controls to enforce that philosophy.

The importance of movement is communicated to me immediately. The very first thing that happens upon a new game is three hulks lunge from the darkness. They dress as stereotypical hillbillies in flannel shirts and jean overalls. Each wields a growling chainsaw they use to try and carve the player character into pieces.

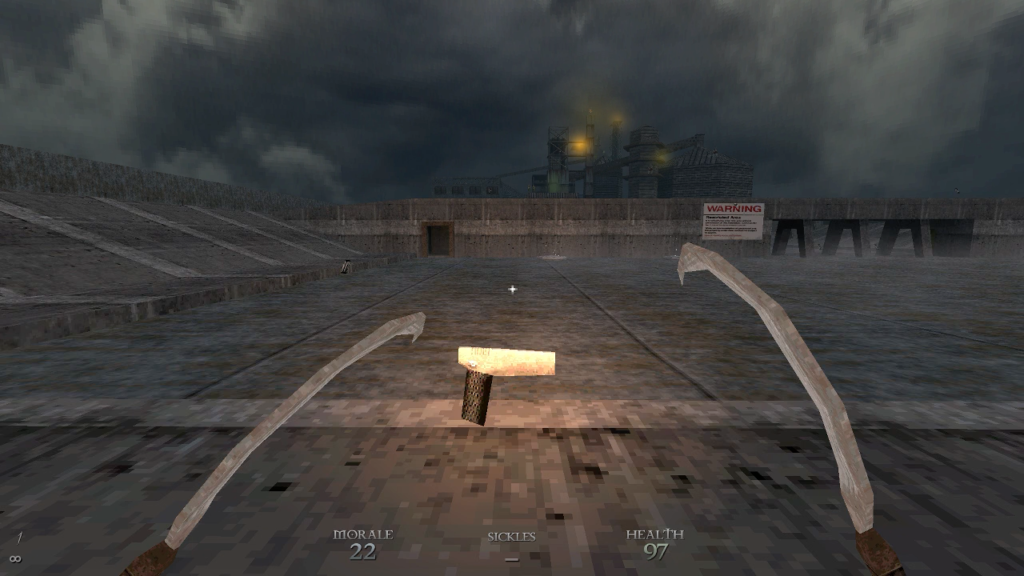

I must dispatch this deadly trio wielding a pair of dull steel sickles. This daunting task proves easy once I realize how quickly I can attack, darting in to strike with a sickle then sliding back out to avoid a wild swing from their chainsaws—which may even hit one of their compatriots instead, prompting them to turn on eachother. Even in the cramped confines of the basement, my superior speed lets me run rings around my opponents. In the first seconds of Dusk, I learn that I am not the hunted. I am the hunter.

Past the Sickles, I acquire a mostly-predictable assortment of first-person shooting weaponry. There’s the prerequisite pistol, a pump-action shotgun, a machine gun, and a rocket launcher. Some of these may be dual-wielded if I can find two. Again recalling Quake, there’s a second tier shotgun that deals much more damage at close range but with a much slower fire rate, so anything that doesn’t die from the first volley is free to punish me with pain.

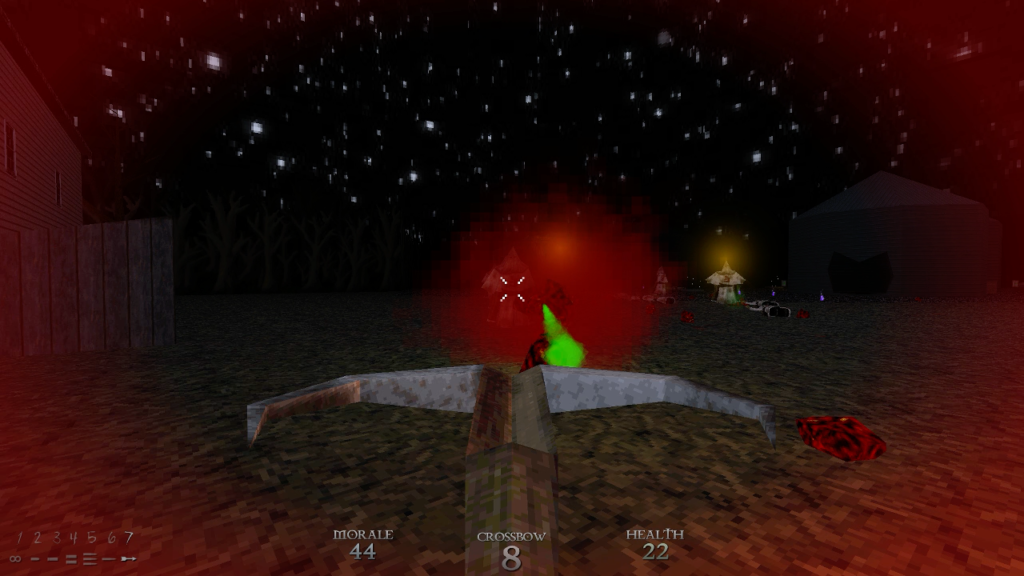

My armory is not completely ordinary throughout. A bolt-action rifle has incredible accuracy and power at the cost of a slow firing rate—not unusual in a first-person shooter, but highly unusual in this style. A grenade launcher’s projectiles will not explode until I press a secondary fire button, letting me lay traps or wait for enemies to cluster together for maximum effect. Most unexpected is a crossbow whose bolts pierce through enemies, becoming an interesting choice in levels where many weak enemies cluster together.

It’s the sword which is introduced in Dusk’s third episode which is the most interesting. Until that point I am mystified by a statistic called “Morale” which exists alongside the player character’s health. I can increase Morale by finding treasure like gold coins and diamonds, and it falls whenever the player character takes damage. Nothing tells me what Morale does. At least, not until the third episode, when I pick up the sword and at least some of its effects are explained.

With fifty or more Morale, I can hold the sword up to deflect attacks at the cost of a single Morale point. With one hundred or more Morale, the sword’s already-powerful basic swing may be charged to deal even more damage. These abilities are game-changing. They give me the ability to face down my deadliest foes rather than trying to outmaneuver them, at least as long as my Morale holds out, switching up the pacing and intensity.

When I am wielding Dusk’s sword, it feels for the first time like its own videogame instead of an homage to twenty-five-years-old Quake. I only wish one is thrust into my hands sooner. It’s possible to acquire a sword early on if one knows where to look, but I’m not guaranteed to wield one until the third episode. Dusk would do itself a service to establish a unique identity as soon as I begin a new campaign from the main menu.

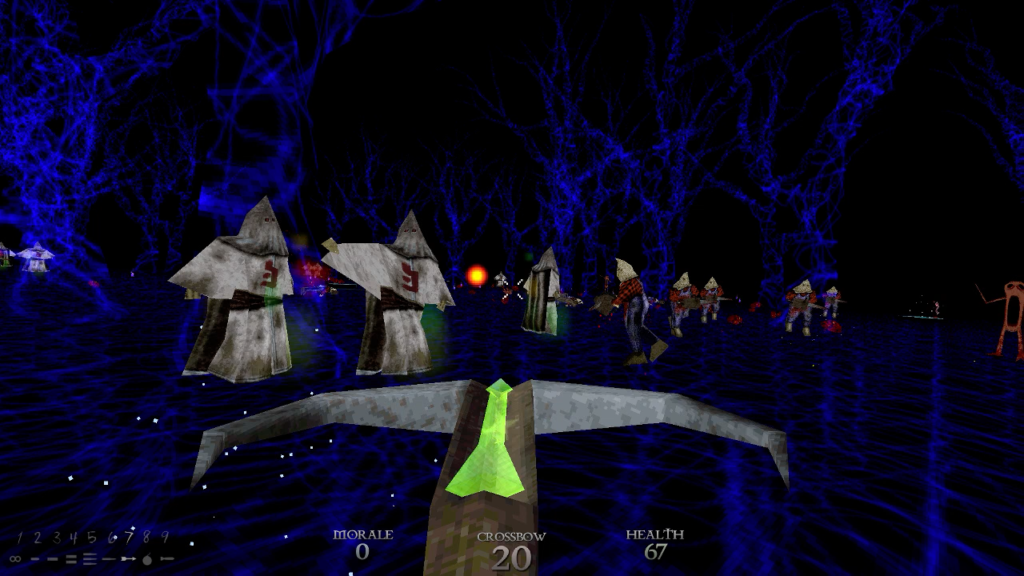

Dusk is divided into three different episodes which may be attempted in any order, and the first is the most conventional. I would even call it rather bland. It charts the player character’s escape from that basement and subsequent rampage through the farmlands outside Dusk. The area is populated by more chainsaw brutes, men in white robes and pointed hoods who fire magical orbs (a literal Klan Wizard in a tasteless pun), rotting undead goats, and walking scarecrows armed with shotguns.

There isn’t much imagination in Episode One’s level design. Barns and houses, packed with cultists and their demonic creations, stand between long empty fields where other cultists wander. I have to ransack every building to find the red, blue, and yellow keys l need to open every door and find the level exit. I am tickled by the “cornfields” which are textures placed on solid walls, a nice throwback to 90s videogame design before packing an environment with thousands of individual corn stalks was a viable choice, but the mazes constructed by these “cornfields” are rudimentary and unchallenging. Episode One feels more like a proof-of-concept than a fully-realized videogame, a series of practice levels, or a shareware release.

My enjoyment improves starting in Episode Two. Here I move beyond the town of Dusk to a military industrial outpost on the edge of town. Most enemies are replaced by soldiers who are much more capable of hitting me from a distance with their rifles than Episode One’s slow-moving chainsaw brutes and shotgun scarecrows. More mechanical horrors, part-human and part-machine, put up much more of a fight as well.

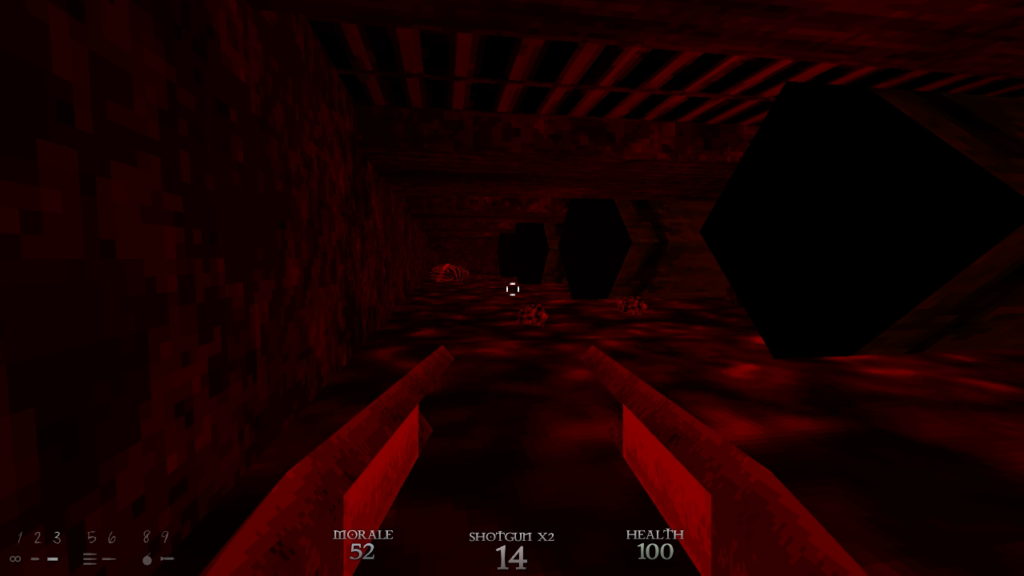

Most of my increased enjoyment attributes to Episode Two’s level design, which explodes in scope and ambition. I first feel this in The Infernal Machine, a level that has me squeezing through the pitch black innards of a massive engine filled with spinning sawblades and crushing gears. It begins with a long fall which breaks the player character’s flashlight, forcing me to grope through the darkness to find a path forward—which is how I notice the entire level is caked in human viscera.

The darkness and gore isn’t just used to make The Infernal Machine Dusk’s scariest and grossest level. The human resources created there have a specific purpose, and when I find their use at the bottom of the factory, Dusk’s implied storytelling takes a big step forward.

Episode Three also has some impressive level design. Beyond the factory I find spaces filled with gothic cathedrals, dungeons where yawning, groaning creatures lurk in dark corners, and pocket universes that don’t make coherent sense to my human eyes.

Most notable in Episode Three is Homecoming, a return to the Dusk township, except it’s floating in a void where space has no meaning. I assume a slip from a floating island will be deadly, but when it finally happens I look down and see the island I just fell from approaching my feet. I must use this curious aberration in space, a tiny pocket universe of memories, to reach the rooftops of the sealed houses to loot what’s inside them. Homecoming feels like an apology for Dusk’s first episode, putting a much more interesting twist on its ordinary setting.

In Dusk’s last two levels it seems to run out of ideas. Gone is the suffocating gore of The Infernal Machine. Absent is the mind-bending physics of Homecoming. Instead, I must slog through a floating island containing over 270 of every kind of enemy in Dusk. There is no cover. Ammunition and health recovery is scarce. It puts every inch of my mastery over the movement systems to the test and not a single moment of it is fun.

The last level contains two boss fights, one an interesting twist on boss fights I don’t want to spoil for Quake fans, and the next a conventional boss fight against a giant monster with a specific weakness. This final monster does not take advantage of the low-poly atmosphere and incredible movement systems which are Dusk’s best aspects. I am sorry to say I watch Dusk’s credits feeling quite deflated by the final few experiences it offers.

Dusk is a love letter to 1990s PC first-person shooters where the only thing we knew was monsters need to be killed and we get to be the man with a gun who does the killing. It skillfully takes advantage of its low-poly aesthetic to enhance the horror and it feels every bit as good to move around its spaces as in the videogames that inspired it. Not every level is a winner, but there is an obvious rise in the skill and artistry put into its level design. The only disappointment is this rise transforms into a plummet as I near the climax. Dusk begins with a furious melee battle in a filthy basement. It ends with a giant monster with an obvious weakness. I force myself to remember the good levels because I don’t want that to be my last impression of a great retro first-person shooter.