CrossCode is a retro 16-bit action RPG set on an alien moon called Shadoon. When humanity reached Shadoon during its interstellar expansion, they discovered it is seeded with a xenoforming system called The Track. Installed by an alien race called the Ancients, the Track ensures any changes made to Shadoon’s surface are soon reverted. Humanity’s unique response to this problem: Turn Shadoon into a Massively Multiplayer Online RPG called CrossWorlds. Using a sophisticated computer program called the CrossCode, players login to Avatars made of ultra-light Instant Matter and try to solve the mysteries left by the Ancients by exploring the Track.

Into this setting comes a player named Lea. Her mind is smuggled into CrossWorlds by a computer programmer named Sergey who explains that in the real world, Lea is in a coma. This condition leaves Lea without her memories and unable to speak, but Sergey offers her some hope: Her memories may exist somewhere on the Track. With Sergey watching her progress and providing advice, Lea must play CrossWorlds, mingle with its players, and complete the Track in order to return her consciousness to her comatose body in the real world. But whenever Sergey logs Lea out from CrossWorlds to rest, she has strange dreams which make her suspect something much more sinister is going on.

CrossCode’s intriguing premise is that it’s a traditional action RPG that uses an MMORPG as its setting. Lea participates in all kinds of normal MMORPG activities during her search. She completes quests to earn rewards that make her stronger. In town, she can trade large quantities of common materials at an auction house for better equipment. She makes friends, joins a guild, and goes on a raid. But where other CrossWorlds players are there for fun and to escape their busy lives, Lea’s experience is deathly serious. Her future existence depends on her ability to complete the Track and find her lost memories.

This mission is made more complicated by Lea’s amnesia and inability to speak. This aspect of her character feels deliberately meta. In the 16-bit RPGs CrossCode borrows from, player characters were frequently both amnesiac and silent to create a totally blank slate for players to impose their own identities onto. Lea, in contrast, is a real person with a personality, opinions, and things to say, all of which she has great difficulty expressing. Much of the plot’s drama is generated by Lea’s inability to communicate her situation to the friends she makes in CrossWorlds—a situation they likely wouldn’t believe if she could tell them.

The MMORPG setting informs other aspects of the plot and design. Rather than gathering her party at an inn or save point, Lea can send party invites to her friends from an in-game menu—but only if they’re online at the time. Sometimes Lea must go solo when her closest friends, Emilie and C’tron, are occupied with their commitments on Earth.

Lea also makes a rival who dogs her throughout her journey. Due to the circumstances of her entrance into CrossWorlds, Lea is one level higher than other players when they emerge from the tutorial dungeon. A player named Apollo notices this and becomes enraged by her cheating. He spends the rest of his time on the Track challenging Lea to duels while making grandiose proclamations about her worthiness as an honorable player. It’s such an authentic representation of how some players treat those they feel are disrespecting their favorite videogame that it’s exasperating. Apollo feels especially genuine to me because it’s exactly how I reacted to hackers in Diablo in the early years of online videogaming.

Lea’s journey along the Track takes her across the standard videogame environments like a verdant field, a snowy mountaintop, a barren desert, and a wild jungle. These areas would be eye-rolling tropes in any other RPG, but as with Lea’s amnesia, it works here because the setting deliberately indulges in clichés while also justifying them with lore. CrossWorlds may be too conveniently divided into coherent biomes, but it’s the fault of the Ancients who installed the Track on Shadoon and not CrossWorlds’ overworked creative team.

I cannot overstate how good it feels to move through these environments. Lea is fast, rushing from one side of an area to another in seconds, but the incredibly responsive controls never turn her speed into a liability. It’s exhilarating to sit down with what appears to be an ordinary action RPG, where a player character’s movement is typically plodding at best, and find one who handles with the speed and precision of a race car.

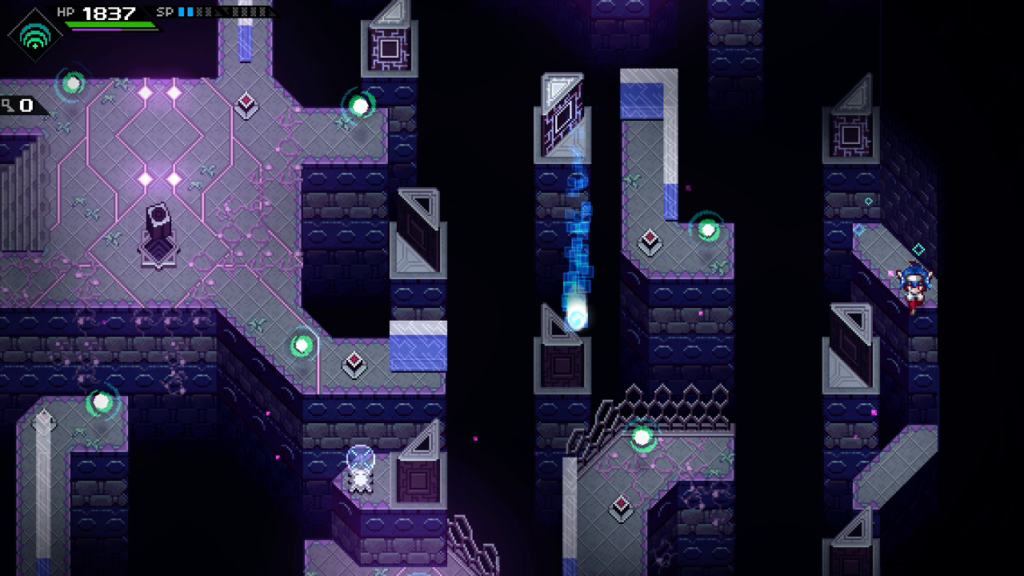

When Lea reaches a ledge that rises no higher than her waist, she can hop up to a new elevation. Valuable items and quest objectives are often placed on high cliffs and finding a path to reach them becomes a kind of labyrinth that winds throughout each area. Lea might be able to see a chest sitting on a high cliff on one screen, but the ledges she needs to jump up to reach it may be several screens away. I must guide Lea along these perilous paths to reach her rewards, unlocking new routes and shortcuts along the way. I never mind doing so because the simple act of traversing CrossWorlds is such an effortless joy.

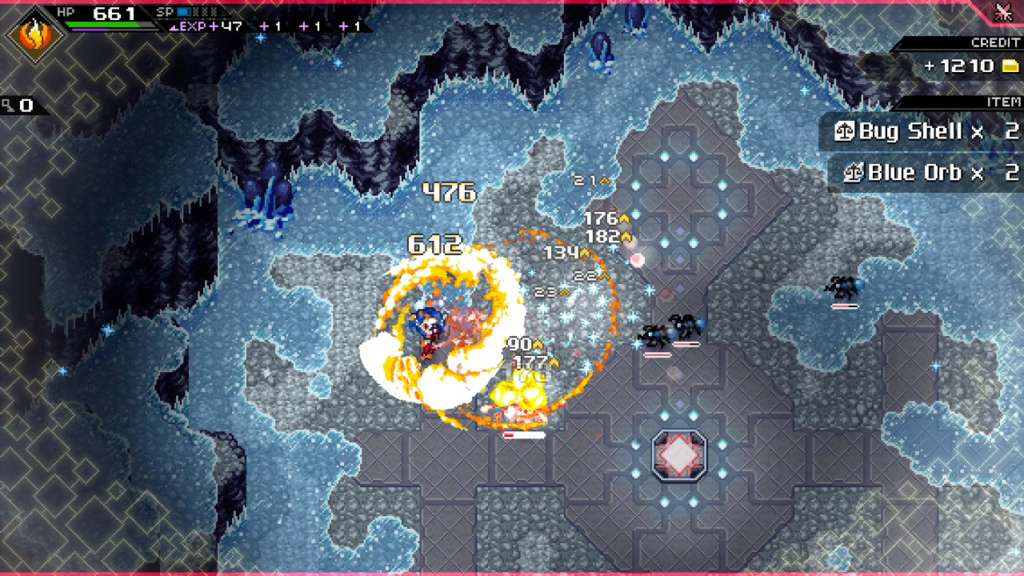

Lea’s CrossWorlds avatar is a Spheromancer class. Regarded by CrossWorlds’ players as the most difficult class to learn, Spheromancers are an uncommon sight along the Track. They fight in melee combat using razor sharp rings. From a distance, they unleash a flurry of damaging orbs. By switching between four available elements, Spheromancers can apply hindering status effects to monsters and take advantage of their weaknesses.

Defensively, Spheromancers have two options. Blocking locks the Spheromancer in place and creates a barrier which greatly reduces the damage dealt by monster attacks, but breaks if it absorbs too many. For attacks too powerful to be blocked, Spheromancers can dodge. Dodging provides a brief window of invincibility and carries the user a short distance away, potentially letting them avoid attacks entirely.

Defensive play is an exercise in precarious timing. If I hold the block button down, the barrier absorbs less damage and wears down faster. It’s riskier but much more effective if I wait until the last moment to block a monster’s attack. Similarly, dodging does not carry Lea far, so attacks must be dodged at the last second. Spamming dodges and blocks is already ineffective at the adventure’s start, but by the end if I’m not blocking and dodging as late as possible then Lea will die just as surely as if I take no action at all.

Offense and defense are complicated by Combat Arts. As Lea attacks, she builds up charges on a combo meter which she can use to enhance both her offensive and defensive abilities. Combat Arts add a spectacular amount of depth to what at first seems a bare-bones combat system. A melee attack, a ranged attack, a block, and a dodge are not much to keep track of in the early areas, making CrossCode’s opening hours a bit hack-and-slashy. This changes when Lea starts to learn Combat Arts for all these basic skills. Combat Arts can be charged up to multiple tiers with new results.

Changing Lea’s element further alters her Combat Arts’ effects. With the Fire element, Lea’s melee Combat Art unleashes a bevy of kung fu blows that leaves monsters burned. With the Ice element, her block Combat Art absorbs a monster attack and counters for devastating damage and a freezing effect on the target. Using the Wave element, the dodge Combat Art leaves behind an illusory copy of Lea which will distract monsters for a few seconds. The Shock element transforms Lea’s ranged spheres into a swarm of electrified orbs that home in on a monster, stunning them.

These deceptively-complicated combat systems are where I experience the most difficulty with CrossCode. Movement is effortless. The combat systems are less intuitive. Perhaps reflecting the opinion of CrossWorlds’ players that the Spheromancer class is difficult to learn, I am more than halfway through the sixty hour duration before I feel I am applying all of Lea’s tools effectively in combat.

I believe my difficulty with the combat systems is due to a lack of explanation. When I unlock new abilities there is a short tutorial on how to activate them, but these tutorials don’t account for context. With nothing to tell me when I should use certain abilities and few areas which teach me, I fall back to the first tactics I learn: aggressive use of basic melee attacks on most enemies, and spheres on enemies who avoid melee. An offense-heavy strategy becomes increasingly ineffective as time goes on and it’s only through repeated punishment from tricky enemies that I learn to take a more precision approach to combat.

Lea’s Spheromancer abilities are also used to solve dungeon puzzles. Her primary puzzle solving tool is the first sphere she throws with her ranged attack which is “charged” and capable of ricocheting off walls. By bouncing a charged sphere enhanced by an element around a dungeon floor, Lea can activate the many mechanisms which form the basis of CrossCode’ clever puzzles.

The first such mechanism I encounter is a floating bubble. When struck with a Fire-imbued sphere, the bubble bursts in a cloud of steam which can briefly power wind generators dotted around a room. These generators open doors and activate floating platforms, so I must race through them before the generators run out of energy and the path forward is once again blocked. The floating bubbles appear again in the next dungeon, but there Lea masters the Ice element. By freezing ice bubbles into a block of ice then sliding it into an oven, once again steam energy is created which briefly powers machines in the rooms.

These are only the simplest interactions between Lea’s powers and dungeon machinery. There’s an astonishing number of mechanisms which interact with all four elements in surprising and unexpected ways. Best of all, no puzzle ever appears in quite the same configuration twice.

Each dungeon culminates in a room-filling “super puzzle” where Lea acts as a mobile cog in a Rube Goldberg machine. Only by activating mechanism after mechanism in a precise order with exact timing will the dungeon’s final door open, revealing Lea’s next milestone on the Track. Whether I’m doing the simple, door-open door-close puzzles early in a dungeon or the Mouse Trap-esque super puzzle at its end, CrossCode creates an incredible series of intelligent obstacles to think my way through. They are, in a word, genius, among the best puzzles I’ve encountered in any videogame I’ve ever played, and worth the price of admission alone.

CrossCode’s precarious combat and intricate puzzles require precise timing to overcome which is an obstacle to players of different skill and ability levels. Mistiming a dodge or block can lead to a devastating attack. Many dungeon puzzles allow for zero margin of error, a single mistake forcing a restart of an entire puzzle sequence.

CrossCode thoughtfully includes several assists to minimize these pains. Puzzle speed can be reduced by half, doubling the time needed to scamper through a door, leap to a moving platform, or activate the next trigger in a puzzle sequence. Enemy attack rate can also be reduced by half, giving more time to heal and plan Lea’s next move. Best of all, enemy damage can be dropped to one-fifth of the standard, allowing Lea to plow through most of her obstacles with stubborn fortitude.

I manage to complete CrossCode without turning on any assists. It isn’t always a pleasant experience, especially accounting for my harsh learning curve with the combat systems, but it is comforting to know the options are there. And it’s always nice when a videogame, especially one as smart and thoughtful as this one, provides an avenue for players of all skill and ability levels to enjoy them.

Lea’s Spheromancer abilities are not put to great use in all of CrossCode’s features. Several sidequests are actually minigames, including tower defense and point-defense horde modes. In addition to being incredibly hard—I never manage to finish the horde minigame even on its easiest difficulty—they are not fun to play, compounding Lea’s fragileness with aggressive enemy attacks in marathon-length waves of enemies. These minigames are repeatable, as I am intended to earn rare items for completing them. They are, thankfully, also completely optional and I avoided them because I don’t hate myself and don’t want to hate CrossCode.

At a glance it’s easy to see that CrossCode is visually inspired by RPGs from the 16-bit era, the first golden age of console RPGs. Its soundtrack is similarly inspired. CrossCode’s graphics and music could stand proudly alongside the likes of Secret of Mana and Chrono Trigger, distinguishable only by the better technology it runs on. But it knows where to expand on classic ideas, especially in story-driven dialog sequences where each character gets a large, detailed, and expressive portrait to accompany their written text. It’s a deft combination of classic aesthetics with modern sensibilities, resulting in a final product that looks and sounds wonderful.

Almost everything in CrossCode is stellar. The setting is detailed and thoughtful, filled with likably flawed characters enmeshed in a story filled with twists and surprises. The combat systems, while not doing a great job immersing me into their nuances, are dense and filled with challenge and strategy. Lea glides through CrossWorlds in a way that feels both effortless and deliberate; it simply feels good to move in a way few other videogames even hope to aspire to. The puzzles which block Lea’s path forward on the Track are the real star. I do not casually use the word “genius” to describe them. I’m not trying to sound hyperbolic; CrossCode is just that good. It’s easy to recommend this videogame to fans of the 16-bit RPG era, but its many assists make it accessible to a broad audience who might be interested. CrossCode is a standout indie RPG.