Griftlands is a deckbuilding RPG set on a corrupt and criminal alien world named Havaria. I choose to play as one of three characters called Grifters. Each Grifter explores a unique location and has their own goals, but their quests intertwine them with the same factions and the self-serving leaders and followers within them. Everyone on Havaria has their own agenda, and only by exploiting their motivations or challenging them in combat can I work towards my Grifter’s goal. Success takes all my skill and luck. Not everyone has what it takes to survive in the Griftlands.

Deckbuilders are a variation on turn-based RPGs where instead of building statistics to represent my player character’s attributes, I build a card deck. I attack, defend, and perform other actions by playing cards from a hand drawn from my deck. I spend the entire campaign building and improving this deck—hence the name “deckbuilder.” Griftlands is unremarkable in the genre. I begin a campaign with a basic prebuilt deck and I can add or remove cards from it by winning battles and completing quests.

For my deck to succeed I must minimize “the luck of the draw” as much as possible. I do this by improving my existing cards into better versions, adding cards which synergize with those improved cards, and removing cards which do not. There’s no rule dictating how many cards have to be in my deck; often the most powerful decks will contain fewer than a dozen cards. Over the course of many campaigns I develop a thorough knowledge of the cards I can add and remove from each Grifter’s deck, shifting strategies on the fly as I discover new cards with new synergistic possibilities.

At the time of this writing there are three Grifters with three unique decks and three distinct campaigns available in Griftlands. At the start I can play as Sal ik-Derrick, a bounty hunter out for revenge against the crime boss who sold Sal and her parents into slavery. After playing as Sal for a few hours I unlock Rook, a retired spy who is blackmailed into acting as a double agent in a violent dispute between a union and their employers. After some time in Rook’s shoes I can begin Smith’s campaign. Smith is the black sheep of a powerful family, more interested in drinking and brawling than matching his sibling’s high-status careers, but he is incensed when he learns he is shut out of his inheritance and sets out to confront the other heirs.

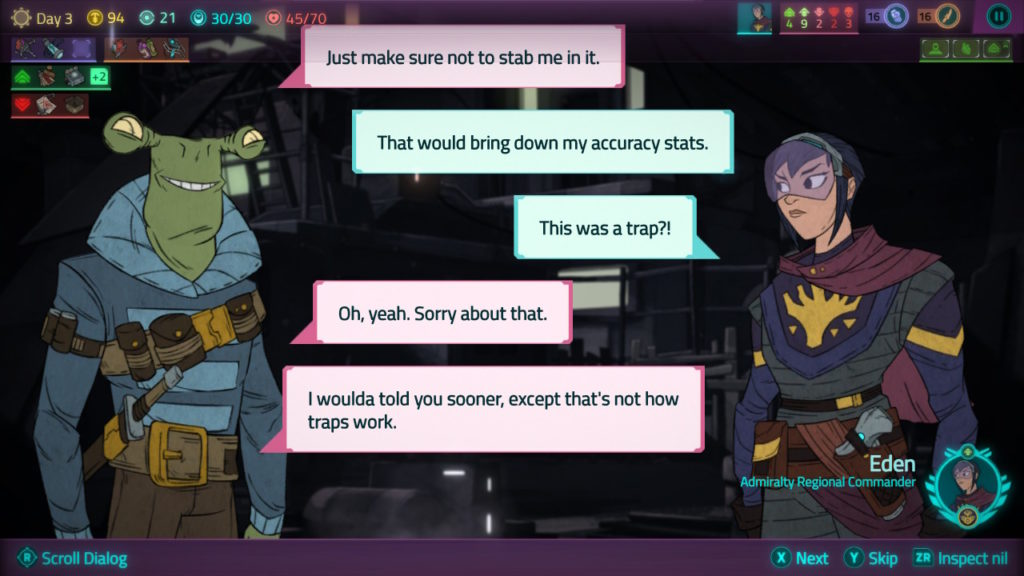

All three Grifters are interesting to play because all three subvert traditional videogame heroics. They’re selfish and conniving in their motivations, and depending on my choices can be backstabbing, bloodthirsty, or immoral. Even Sal’s standard revenge plot does not quibble that, whatever her justifications, she is a hired killer in a world filled with them. They’re Grifters in the Griftlands, and not even antiheroes can survive here.

The three Grifters also highlight the incredible flexibility of the deckbuilder genre. No matter who I play as, each battle proceeds by drawing and playing cards from the deck. Despite this commonality, each deck uses unique mechanics that makes playing as each Grifter feel like a completely different RPG.

Sal is a classic Rogue, able to generate combo points that enhance the power of her attacks and inflict bleed effects on enemies that stack to devastating effect. Like her comparatively bland revenge story, her skillset is the most basic of the three Grifters. It feels deliberate to me that Griftland’s first character has its most familiar abilities, easing veterans of more traditional RPGs into cardbuilder systems.

Rook is where things get more unorthodox. He uses a custom blaster that builds charges each time it is fired. Other cards become more or less effective depending on the number of charges he stores. He is also infected with an alien parasite shortly into his campaign; I can try to avoid playing the parasite’s cards which can damage Rook, but if I do use them they eventually evolve into powerful attacks.

Smith is where Griftlands’ combat mechanics get truly unique. He has a mundane and effective hammer to fight with, or I can choose to lean into his alcoholic tendencies. Using Smith’s drink cards gives him various buffs and adds Empty Bottles to his deck. The more Empty Bottles I have, the more effective some of his attack cards become.

These are only the mechanics that appear in each Grifter’s default deck. The more I play as them, the more new “booster packs” I unlock. Booster packs add new cards to each campaign which I may find in my next attempt. Some only make the Grifter’s default mechanics more effective. Others add entirely new complications to the combat systems. I can keep playing Griftlands for hours and still discover new cards that provide new strategic possibilities.

It’s a poor Grifter who always uses violence to get what they want, so as often as not it’s a better choice to talk my way out of a situation. When I try to convince an NPC to do something I enter a Negotiation. Negotiations are represented by a completely different kind of card “battle” that uses a completely different deck. Like in a Battle, I attack and defend using cards played from my hand. Unlike in a Battle, buffs become “arguments” on the field with their own hit points. To succeed I must spend as much time attacking enemy buffs and defending my own as I do attacking my opponent’s core argument while protecting my Grifter’s.

Much like the Battles, each Grifter brings unique mechanics with their Negotiation decks. Sal builds stacks of Influence or Dominance which boost the power of her Diplomacy and Hostility cards respectively. Rook employs his lucky coin. I flip the coin every turn, and whether it lands on heads or tails changes the effects of his cards—and I can cheat to force the coin to land how I want. Smith builds stacks of Fame that automatically damage the enemy every turn, but Fame is fragile and if the opponent can destroy the buff it deals huge damage to Smith.

What makes a Negotiation especially interesting is it’s not necessarily a hostile action. Often I will engage an ally in a Negotiation and they may take it personally if I convince them to do something they don’t want to do. Losing a Negotiation doesn’t result in a game over, so it’s nearly always worth it to enter one when the option is available. Succeeding can earn valuable rewards and assistance. Several boss battles seem almost impossible without first gaining some kind of advantage with a Negotiation immediately preceding the proper fight.

Playing the Switch version, Negotiations are where I encountered the most difficulty with Griftland’s UI. Negotiations use a distinct ring-shaped interface even though mechanically they’re not all that different from standard card Battles. It’s easy enough to highlight different parts of the interface with a mouse cursor, but the Switch version requires a few too many extra button presses to highlight certain details. Worse still, important information is often hidden behind other UI elements, such as how many hit points individual arguments have remaining. As a turn-based videogame these problems aren’t insurmountable but they can be annoying.

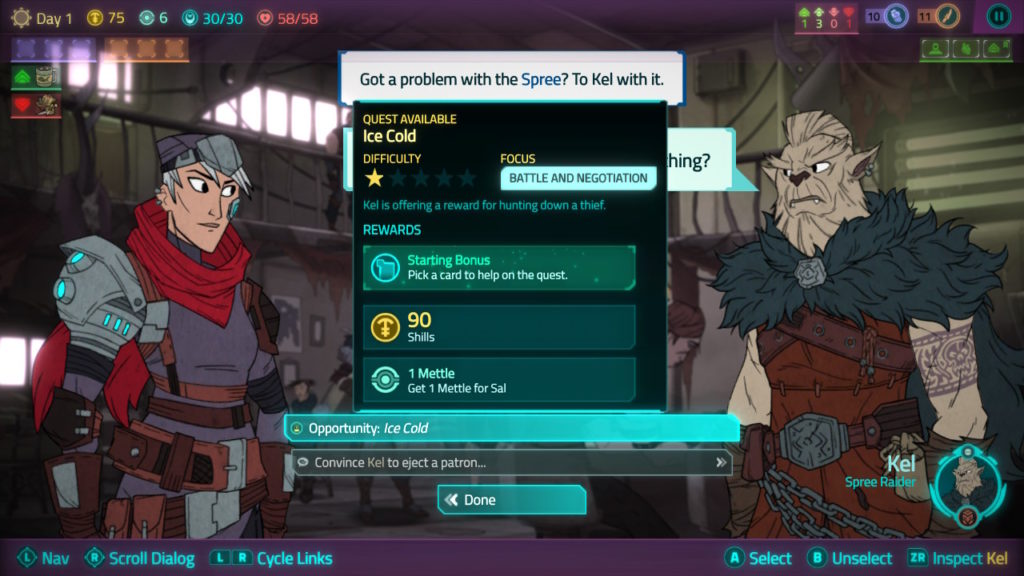

My Grifter engages in Battles and Negotiations while completing quests that build toward their ultimate goal. Quests are drawn from a pool of dozens unique to each Grifter’s campaign. I only complete a handful of quests in a complete campaign so I have to keep playing for a long time to see them all.

Each quest pool is tailored to each Grifter’s personality, making each campaign feel like a completely different RPG. Sal, the bounty hunter, accepts jobs to hunt criminals and protect VIPs—or vice-versa. Rook, the spy, alternates between intimidating strikers and terrorizing property owners, giving him a glimpse at both sides of the class conflict. Smith, a stinking drunk trying to get close to his successful siblings, seems to stumble from one farcical fish-out-of-water adventure to another.

It doesn’t take long for me to start seeing repeat quests, but the flexibility provided in completing them somewhat alleviates the tedium. Whether I choose to Negotiate, Battle, bribe, or even ignore certain parts of a quest can lead to different outcomes. This keeps the repeats interesting, but when even my interest starts to wane there’s a handy fast forward button to skip right to the important decisions.

How I behave while completing quests affects my Grifter’s social standing. There are dozens of NPCs occupying the Griftlands and how I treat them can make a campaign much easier or harder. Killing someone in battle is a quick way to make enemies of their friends. A small bribe can turn a bar’s bouncer into my ally, who I can then ask to eject a troublesome patron. Giving someone in a bad situation a break can earn their loyalty, and they may join me in my next Battle or support me in a Negotiation if I encounter them again later. The opposite is also true, and making an enemy may cause them to join the other side of a Battle or Negotiation.

The most helpful elements of this social system are the Boons. Its most unhelpful are called Banes. If I make someone like me enough I gain their Social Boon, which adds a helpful bonus that follows me for the remainder of the campaign. With the Bargaining Boon, everything costs twenty fewer Shills in the Griftland’s shops. With War Machine, I can request free rocket launchers from members of the Rise faction.

But the opposite is also true, and leaving a long list of betrayals and dead bodies behind can create an unsurmountable list of Banes dragging my Grifter down. With the Bad Credit Bane, everything costs twenty more Shills in the Griftland’s shops. The Red Tape Bane prevents members of the Admiralty faction from assisting me in Battles and Negotiations.

Like any Grifter, I must practice restraint. Behaving too recklessly or too obviously in my own interests makes more enemies than my wits can handle.

I have an interesting experience with Griftland’s difficulty. In my first campaign with Sal I am annihilated by the second boss. I shrug this off, assuming I need to unlock more of her booster packs to get her better cards. I unlock Rook in this attempt and decide to see how far I can get with his campaign. To my amazement, I go all the way on my first attempt. The same thing happens with Smith. Thinking I must have subconsciously absorbed some deeper mechanical understanding, I return to Sal’s campaign. I make it all the way to her final boss… and then die again. And then again. And then once more. It’s over a half-dozen attempts before I finally see Sal get her revenge.

There’s something about Sal’s campaign that feels more difficult to me than Rook’s or Smith’s, even though they have more technically complicated decks. For one thing, Sal’s campaign is slightly longer, giving me more chances to make mistakes and more opportunities to build up Banes. Her bosses are also much less forgiving of mistakes, with the second and final bosses in particular demanding certain strategies that take me multiple attempts to fully grasp. Since many bosses have multiple iterations with differing abilities, what I learn in my last attempt may not even apply in the next. With each campaign taking about four hours to complete, dying to a final boss’s trial-and-error mechanics feels demoralizing.

Even when I have completed each Grifter’s campaign, Griftlands is far from over. When I defeat a final boss I unlock that campaign’s next Prestige tier. Prestige adds new, more complicated mechanics to enemy decks. A strategy that decimates my opponents at Prestige 0 is less reliable at Prestige 1, and by Prestige 4 may well be useless. With seven Prestige levels to clear for each Grifter campaign, there’s literally hundreds of hours and hundreds of failed campaigns ahead of me if I want to fully complete Griftlands.

Thankfully I am aided along the way by Mettle, a meta progression system that rewards each Grifter with points when I complete nearly any action. I can spend these points at a black market to enhance each Grifter’s abilities. I can increase their health in Battle and Negotiations, the rate their cards upgrade to their next level, and the amount of Shills needed to buy items.

Mettle is a nice system that ensures I gain something from even the most abysmally failed campaign, granting me the slightest boost for my next attempt as I work my way up to Prestige 7.

With its story-driven design and approachable mechanics, Griftlands is a great entry point to the deckbuilder genre. It makes me appreciate the flexibility of deckbuilders, how changing which cards are available to which Grifters can make me feel like I’m playing a completely different RPG governed by new rules.

Not only is Griftlands mechanically smart, the setting is equally brilliant. The playable Grifters are scoundrels, but still likable—even the greedy and slovenly Smith. The Griftlands themselves reflect this dichotomy, a filthy swamp where honesty is a vice and generosity a suspicious commodity. I wouldn’t want to live there, but I’m happy to visit in the form of these avatars.

It might be too much to ask, but I hope Griftlands gets supported in the long run with new Grifters and campaigns the way Klei Entertainment has supported Don’t Starve with new content for years. It’s already an incredible deckbuilder RPG, but if it gets that same kind of long-term support it could become one of the all-time greats.