Hollow Knight seems unremarkable at first. It is an non-linear platformer, with all the design tropes expected from that well-worn genre. I play as the Knight, an anthropomorphized bug with a featureless white head who explores an open, side-scrolling world. My ability to maneuver through this world is initially limited by the player character’s rudimentary moveset. As I discover tools which enhance their platforming abilities, more and more of the world opens itself to me. When I have applied all these tools to enough corners of the world, I discover a path to the final area where I face the entity that rules the world I have mastered. Hollow Knight hews to this familiar design philosophy, but deviates just enough to stand out. These deviations emphasize exploration over empowerment, forging a non-linear platformer that rewards skill and curiosity instead of percentage completion points.

The real star of Hollow Knight is its setting: Hallownest, a ruined insect kingdom buried in earth and time. My first entrance into its depths is through a well on the outskirts of a ghost town called Dirtmouth. Dirtmouth’s lone holdout, the Elderbug, warns the Knight that bugs who venture into Hallownest are stripped of their memories and driven insane. As I take my first steps into the caverns beneath Dirtmouth I encounter many of these bugs: twisted berserkers who stalk the kingdom’s corridors, searching for trespassers with self-destructive fury. Why Hallownest has this effect on bugs, and why the Knight proves immune to its effects, is the main mystery I will solve over Hollow Knight’s course.

Like the videogame it embodies, Hallownest is deceptively huge. When I first drop down Dirtmouth’s well I find myself in the Forgotten Crossroads, a crumbling tunnel network with many inaccessible paths leading in all directions throughout Hallownest. These passages are misleading, as the world continues far beyond them. Just when I think I’ve reached the bottommost area, I discover a pit or tunnel leading further outward. It is not unusual for an unassuming passage to lead to an entirely new region.

The overwhelming color throughout Hallownest is a deep shade of blue, like a dark rockface illuminated by a full moon. It would be easy to get lost if everywhere I went I only saw this midnight blue, but it is joined by other colors which change from region to region. The Greenpath is an overgrown garden filled with rich, green foliage. The Fog Canyon exudes a pink mist from the jellyfish that float around its narrow ravines. The Fungal Wastes are dominated by putrid brown mushrooms. Deepnest’s primary color is black, creating a terrifying world of suffocating darkness filled with writhing shadows. By intermingling the omnipresent midnight blue with a distinct color unique to each region, I can recognize where I am in Hallownest with a single look. And everywhere I go, I encounter the acrid orange that represents Hallownest’s corruption. It glows in the eyes of hostile bugs and explodes out of them in a cloudburst when they die.

There is no true path through Hallownest. In other non-linear platformers, while the world may be open and interconnected, there is a clear sequence of events which must be followed in a specific order. Some item or ability is procured, usually following a boss fight, and I must backtrack to a previously inaccessible passage to reach the next area. Rinse and repeat until every area is opened and I can challenge the final boss.

The genius of Hollow Knight’s design is how it breaks from that convention. It doesn’t happen right away; to leave the Forgotten Crossroads I must defeat the hulking False Knight and learn the Vengeful Spirit ability, which opens a passage to the Greenpath. This familiar loop continues through a few more areas, but after the Knight has learned to air dash and to jump off walls the traditional veneer is torn off. I am allowed to go almost anywhere in Hallownest I wish, my presence in most areas prevented only by my ability to overcome the enemies who guard it. There are still new abilities hidden away in obscure corners which create new paths forward, but there is no prescribed order in which they must be obtained, and thus no prescribed order in which the new paths must be traversed.

With no real sense of where I need to go next and no particular route I must take to get there, it’s easy to become lost in Hallownest. This feeling is exacerbated by the mapping system. Rooms do not automatically fill in on the Knight’s map when I visit them. I must first buy a map of the local area from Cornifer, another bug who explores the world parallel to the Knight. Until I can locate him, I am forced to wander the immediate area from memory. With many of Hallownest’s corridors looking similar to their neighbors, getting lost without a map to guide me is all too easy.

Yet even Cornifer’s maps only cover each region’s core rooms, so I must purchase a quill in Dirtmouth. It allows the Knight to make additions of outlying rooms when I reach one of the iron benches that marks a save point. Until I can reach those benches, even armed with a map, I will see only a blank void when I consult the Knight’s location with the tap of a button. This system, unorthodox in the non-linear platformer genre, creates a distressing sense of aimlessness within me, especially in Hallownest’s most labyrinthine areas. Hollow Knight makes me feel lost in a way no other non-linear platformer ever has.

By eschewing design choices that have been non-linear platformer dogma for decades—a predictable series of events, a singular path forward, a friendly map to place myself within the world—Hollow Knight forges a new design philosophy that pushes exploration and discovery to the forefront.

My vessel for exploring Hallownest is the Knight. In keeping with Hollow Knight’s theme, the Knight at first seems unremarkable. They are inexpressive and incapable of speech, justifying all the exposition the few sentient bugs I encounter unload upon me. Depending on how deeply I delve into Hallownest’s mysteries, I learn what a remarkable creature the Knight really is.

The Knight has limited abilities. At the outset, I can jump and attack with their sword-like Nail. I uncover a few new abilities for the Knight while exploring, but jumping and nailing is my primary interaction with the world. I can augment these skills with Charms. These badges can be equipped to the Knight in limited numbers and provide effects like increasing the range of their nail, damaging enemies who impact the Knight, or increasing the amount of Soul the Knight generates in combat.

Soul is where the Knight’s abilities get a little more interesting. When I strike enemies with the nail, the Knight generates Soul. Soul can be expelled in great bursts of damaging energy, or focused into healing a single point of damage. Healing takes several seconds and is interrupted by damage, so I must choose my moments carefully. The result is a typical risk/reward system: I can expel accumulated Soul for instant extra damage, or save it to heal when I can manage a few seconds of uninterrupted meditation. Hollow Knight’s most dangerous encounters often don’t give me a choice. Some enemies attack with such ferocity that I never get a moment to heal, so I may as well spend the Soul on extra damage whenever I get the chance.

Platforming is where playing as the Knight feels the most troublesome. The window to jump is not as close to a platform’s edge as I feel it should be, particularly when wall-jumping, so I often find myself jumping just a second too late. This usually results in a fall into a damaging pit.

To make this problem worse, the Knight is surprisingly heavy. They don’t so much fall as they plummet. In most platformers, the double jump can be used to fine-tune a landing, avoiding unwanted falls. I confess that I have become so reliant on this tool that it has caused my precision platforming skill to atrophy. Hollow Knight has a double jump, but it’s one of the last skills I discover. I am forced to explore most of Hallownest without it, and every time I make a mistake the Knight drops with such speed and force that I often have to repeat entire platforming sequences from their beginning.

Hollow Knight’s platforming is not difficult once I discover all its tools, but those tools are not easy to discover. I have to work to reach that level of effortlessness, and by the time I do I have already explored most of Hallownest. With nothing left to prove by the time I earn the Knight’s most powerful platforming abilities, they become conveniences, not necessities.

In other non-linear platformers, the player character’s power level can be gauged by the percentage of the map I have explored. Every room visited and every secret passage broken open bestows the player character with new upgrades as the map gauge inches closer to one hundred percent.

Hollow Knight subverts this design trope through the relative scarcity of its collectibles and the minor improvement they make on the Knight’s base statistics. There are only sixteen health upgrades total sequestered throughout Hallownest. I need four of them to earn a single new hit point, for a mere four extra hit points if I find them all. Contrast to Metroid, where finding all the hidden energy tanks can boost Samus’ starting hit points by over one thousand percent.

This doesn’t mean there aren’t dozens of pickups to discover. Far from it. But even when I have scoured Hallownest of all its collectibles and have the Knight pumped up to maximum power, I can’t simply endure every hit Hollow Knight’s greatest challenges throw at me the way I can in many other non-linear platformers. I must overcome them with practice and skill. Finding all the pickups only provides a little more room for error.

If Hallownest is the star of Hollow Knight, then its bosses are the colorful supporting cast which carry the show even after the star has moved on to a film career. Each boss is finely tuned to push my precision and my application of the Knight’s skills to their utmost. The Mantis Lords randomly charge at the Knight from the side, or thrust down from above. I must make a split-second decision to leap over their charge or dash aside from their thrust. A moment’s hesitation ensures I will take a hit, and their attacks are so ferocious that I will gain almost no chances to reclaim lost hit points by meditating with earned Soul. Only concentration, determination, and practice will see me through the challenge.

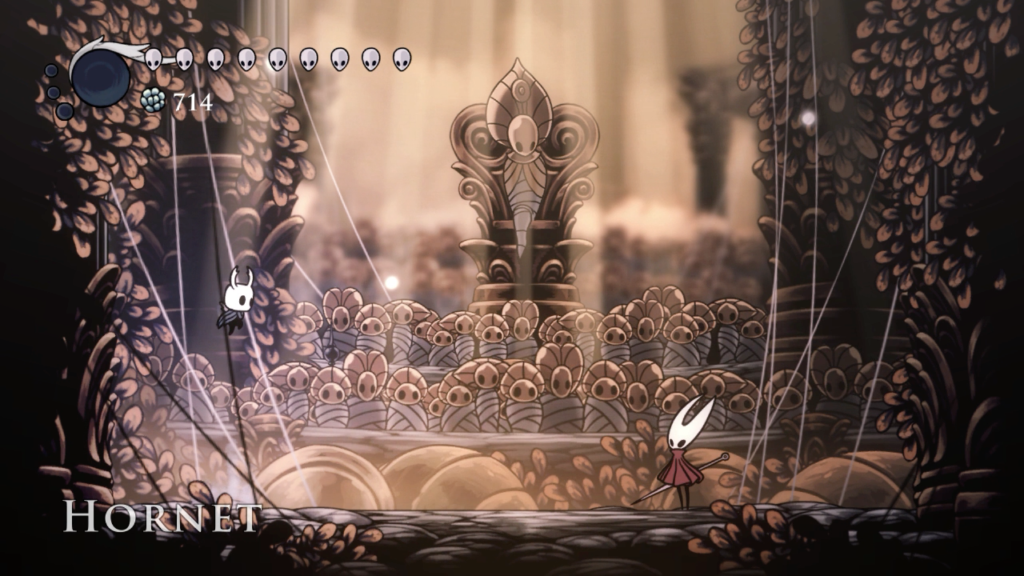

Most of Hollow Knight’s bosses are built on this strategy: jump or dash to dodge their attacks, and counter attack in the brief window of vulnerability that follows. This never becomes tedious due to their creativity and variety. The Brooding Mawlek is a bulbous monster covered in eyes and spikes which flings corrosive acid, then swipes at me with its massive claws when I try to close in to attack. The noble Hornet attacks with a tailor’s needle, diving in from all directions while creating makeshift mines by suspending spikes from delicate threads. The jolly Dung Defender pelts me with its precious dung balls in between diving into the filthy floor, gliding through it like water with mighty strokes of his arms, laughing all the while. Each boss is a delight to discover then overcome, at least until situations where re-challenging them becomes a chore.

When I die, the Knight returns to the last bench I saved at. Most bosses have a bench within a reasonable distance of their arenas. A few notable ones do not. Walking all the way back to the boss every time I die becomes annoying, and two of the hardest bosses—the Soul Master and the Watcher Knight—seem to have their nearest save point placed deliberately far away from where they are fought.

To make matters more irritating, the Knight leaves behind a Shade where it dies which I must defeat to reclaim the lost money it carries. If I fail to defeat the Shade, or die again on the way, all that money is lost. Many bosses have their arenas deliberately designed so that this Shade appears within the chamber, while others do not. This decision seems frustratingly arbitrary.

It’s daunting enough facing a tough boss knowing that I will have to face an additional enemy, the Knight’s own Shade, on the next attempt. Add on to this the aggravation of a potentially long and dangerous walk back from the nearest save point, and some of Hollow Knight’s most challenging bosses could easily drive me to despair.

The longer I play Hollow Knight, the more prominent its bosses become. The first half of my experience is dominated by exploration and delight with the discovery of the unknown. The second half is backtracking to all the bosses I discovered but were unable to defeat when I first discovered them. If I want to truly overcome the corruption that grips Hallownest, I will have to cross and re-cross the kingdom many times in pursuit of these challenges, to the point that my main memory of the experience is not the world, but its boss challenges.

Hollow Knight’s post-release support emphasizes this feeling. Its first major update introduced Dream Warriors, fallen heroes whose graves I can discover around Hallownest. Each of their ghosts offers a new boss encounter.

Next comes The Grimm Troupe. There seems a moment of hope that I will have new things to explore and discover as I am charged with tracking down flames throughout Hallownest. But these flames are all marked on my map, so I must simply walk to them. This feels like busywork. It does culminate in Hollow Knight’s most fearsome boss encounter, however.

The third and final major update is Godmaster, where I am beckoned into a dream world where an audience of mummified bugs bear witness to me . . . fighting all of Hallownest’s bosses all over again. These re-challenges apply new rules to most bosses and even create new encounters out of friendly bugs whose might is previously only implied. My disappointment that none of Hollow Knight’s post-release support adds anything significant to the map is palpable.

I described Hollow Knight as seeming “unremarkable.” Its first surprise is the scale and mystery of Hallownest. Its second surprise is once I have mastered the vast world, it becomes an intensely boss-focused experience. Its saving grace from this misleading first impression is that the boss designs are incredible, challenging, and satisfying.

Hollow Knight is masterfully crafted, but its enigmatic design can be its undoing. It’s not quite the videogame it first seems to be. I believe enjoyment will be determined by familiarity with non-linear platformers. Players experienced with the genre’s conventions will appreciate its deliberate subversions. It places a greater emphasis on curious exploration and precision combat than on ever-escalating power accumulated while following a predetermined path through an open world. I worry that newcomers will see these same elements as difficult, overlarge, and abstruse. Since the collectibles are so easy to find, the world is eventually drained of its mystery. This leaves only the bosses, which are challenging and excellent. I think of Hollow Knight as among the best in its class, but that feeling is predicated on experience. I don’t recommend it to non-linear platformer newcomers.