Ikenfell is an indie RPG with light strategy and heavy timing-based skill elements to keep me engaged with its combat system. It is set in a world where young people come to the titular school to understand and harness their magical abilities, growing into full-fledged wizards and witches. But something has gone wrong at Ikenfell this year: None of the students came home for summer vacation and the school gates are sealed. Maritte, the sister of Ikenfell’s star student Safina, comes to investigate, but is waylaid in the bordering forest by the school’s guardian spirits. Maritte is an Ordinary, a non-magical person, and Ordinaries are not allowed in the school. Just when she is about to fall unconscious to the spirits’ attacks, Maritte’s hands light with fire, a kind of magic never seen before, and she is able to fight them off. Now suddenly a witch, Maritte enters Ikenfell where she uncovers the mysteries of the school’s unexplained lockdown and her newly-manifested pyromancy powers.

If Ikenfell is recognized for anything, I hope it’s for its cast of characters and their complicated dynamics. Maritte and the Ikenfell students who join her party have distinct personalities that carry the plot’s drama but never feel older than their teen years. They are a mismatched group of friends, former friends, and rivals, forced to set histories of bullying and unintended slights aside to confront a threat to the entire school.

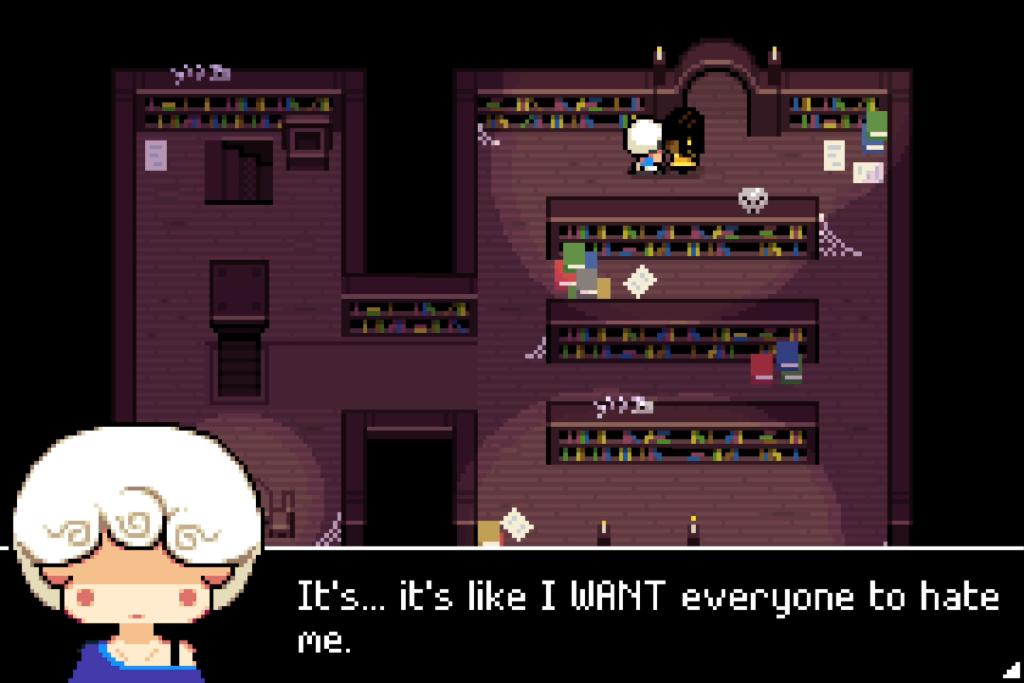

Relationships are portrayed with nuance, showing that bullying rises from social power imbalances that fluctuate from situation to situation. Even the meek Petronella, a talented student alchemist who struggles with self-confidence, finds themself unintentionally and even unknowingly drawn into bullying behavior through their friendship with the popular Safina. Nobody in Ikenfell is an outright bully, showing that anyone is capable of participating in bullying behavior. But neither is the psychological trauma of bullying behavior dismissed, and the person performing this behavior is always shown in the wrong.

Even more important than Ikenfell’s nuanced portrayal of the relationships between young adults is the diversity of its cast. Maritte is a lesbian. Rook, a dark-skinned bookworm, and Petronella both identify as non-binary, but where Petronella uses they/them pronouns and is explicitly aromantic, Rook prefers he/him and was in a relationship with Safina. Ima, one of Ikenfell’s most accomplished senior students, also does not identify with a gender and uses ze/zir pronouns. Ibn and Bax, wizards from the magic FBI who are also investigating the happenings at Ikenfell, are partners in more than the professional sense. In fact, once I am done visiting the small village bar just outside Ikenfell’s walls, I do not encounter a single heterosexual character for the rest of the plot—and I’m only inferring these few characters are straight.

Certain loud voices with an agenda might accuse Ikenfell of being an improbable whirlwind of alternative gender and sexuality, but I find it admirable. I can start any videogame, particularly a AAA one, and invariably find myself in control of a bland heterosexual male archetype who only ever encounters one of the millions of people who fall elsewhere on the gender and sexuality spectrums as tokens—if he encounters them at all. I appreciate that some of these characters have found a home in Ikenfell where they can exist as the norm. It may very well be that in the world of Ikenfell only LGBTQ+ people can use magic at all. That’s a wonderfully empowering idea, especially in a medium that so often fumbles representation.

The most significant part of all this diversity is how insignificant all of it is to the main conflict. Nobody is bullied for their orientation or non-gender conforming appearance. The plot’s driving force is not built around the villain’s homophobia or transphobia. These characters are allowed to exist as they are, saving the world with much less of a deal made about their identities than I have done in this review. It’s a vision of a world that people like me—white, cisgender, and straight—should aspire to.

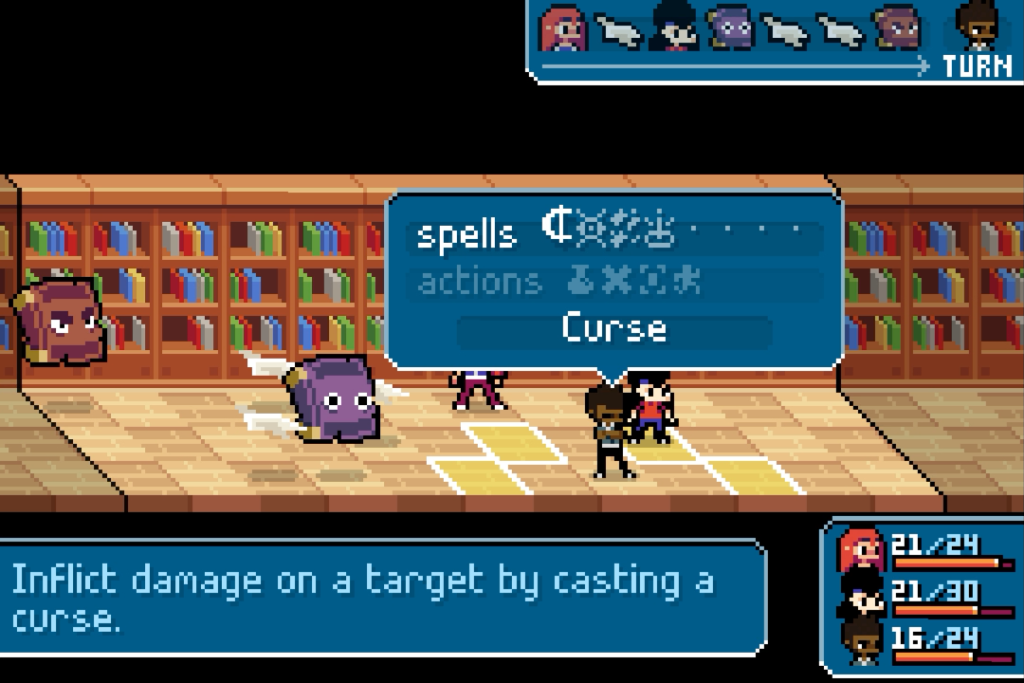

Ikenfell is an RPG, which means Maritte and her new friends are transported to an abstract battlefield when they encounter an enemy. The battlefield is a long and narrow grid, my party of three appearing on the right side and the enemy group appearing on the left. Characters take turns moving along the grid and casting spells.

Each student has a basic spell that targets a single enemy up to two squares away and a utility spell that buffs the party in some way, ensuring a character always has something to do on every turn. Past that character spells are wildly divergent. Maritte’s Fireball hits in a cross pattern and deals good damage but has limited range; Petronella’s Acid Splash has better range, but covers less area and deals less damage; Rook’s Paper Storm strikes in a checkerboard pattern and deals weak damage multiple times. Spells often share traits like this but none are identical, making the party I field equal parts preference and strategy.

Spells are accompanied by short, elaborate animations. By pressing the action button one or more times at key points during these animations, the efficacy of the spell is improved; in contrast, I can also reduce the damage characters take from enemy attacks by pressing the action button just before they are struck. Depending on my timing, I can get an Oops, a Nice, or a Great rating, with a commensurate improvement in damage dealt or reduced.

This Paper Mario-type of attack enhancement is old hat by now, but Ikenfell takes the system a step further by making it crucial to success. Buffs and debuffs do not work at all without Nice timing or better, and if I can’t get Great blocks then bosses will dismantle my party with frightening speed. To make the system even more intimidating, there is no visual prompt on when I must press the action button and every single spell has a unique animation with unique timing. Ikenfell trusts me to feel the sweet spots out, and for the most part I found this intuitive, but I worry how others might feel differently. Thankfully for them, there are toggles in the option menu to ensure action commands always rate at Nice or Great regardless of timing, greatly reducing the difficulty.

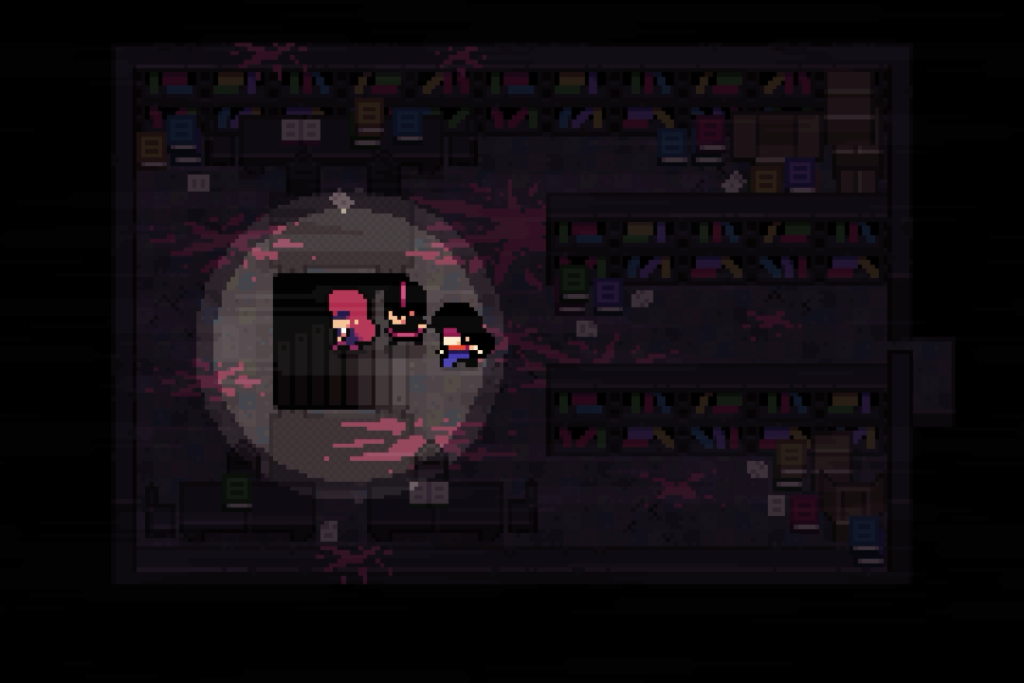

Ikenfell is an imaginative environment. It has the dormitories, libraries, and classrooms expected from a school but with a magical twist. The dormitory doors are sealed with spells by clever students which must be unraveled. The library bookshelves reconfigure themselves in a labyrinth that confounds even its caretakers. The classrooms have descended into chaos; the alchemy lab is overrun by mixtures come to life, while over in the gymnasium-like dueling classrooms training dummies attack unwary students. But Maritte’s adventure isn’t confined to the school grounds, including a memorable visit to the Snatcher’s Lair where lost objects are hoarded by a pilfering monster with childlike curiosity.

The monsters Maritte and her companions combat are equally as memorable. Fallen shooting stars stalk the gardens around the astronomy tower. Misplaced trousers spring to attack in the Snatcher’s Lair. The library’s guardian owl bombards the party with dusty books. Fantasy creatures are no stranger to RPGs, but Ikenfell understands its environment and its creatures feel especially at home here.

Exploring the option menu, I was surprised to find a toggle for Content Warnings. This made me wonder just what kind of videogame I was in for, and I braced myself for a disturbing tale full of substance abuse and sexual violence. Ikenfell, thankfully, has none of these things and coming out the other side of the credits I find myself wondering what needs a content warning—though it isn’t for me to decide what is upsetting to another person. I think it’s important that Ikenfell includes the option and I hope it serves as a model for more videogames in the future. If you feel you might want it, then the option is there. I find Ikenfell’s plot and themes to be mature, particularly in how it emphasizes that the world’s greatest problems come from our individual weaknesses, but does not resort to exploiting humanity’s darkest aspects to achieve that maturity.

I believe this review will let Ikenfell down in the visual department. There’s no denying that in screenshots it looks like a Game Boy Color videogame, but these are only screenshots and when it is witnessed in action it is apparent that these graphics are a choice. Their apparent simplicity does not capture the intricate animations in combat which would stymie the Game Boy Color.

The soundtrack is similarly misleading, beginning with electronic beeps and boops but soon introducing more modern synthesized instruments. Certain boss battles even have full-on vocal performances; it’s quite an experience entering a three-on-three magic duel scored by a nerdcore rap that namechecks Bob Ross and Martin Luther. Ikenfell’s graphics might be a pleasant surprise, but its music is its most impressive attribute.

Ikenfell is fearless. Where other RPGs have generic save-the-world plots, Ikenfell threatens the world with everyday problems, mistakes, and misunderstandings. Where others have bland filler archetypes, Ikenfell has a diverse cast of distinct characters. Where others limit spellcasters to a supporting role and limited mana pools, Ikenfell gives me a party full of witches and wizards with endless magical resources. Where others have over-produced modern graphics or overly-reverential retro graphics, Ikenfell’s visuals are distinct and serve its combat system. It’s a surprising and charming indie RPG.