Seiken Densetsu 3 was never released for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System. This may have been for a number of reasons: Outside Japan, RPGs were still a niche genre before Final Fantasy VII’s marketing blitz thrust them into the mainstream, so there was little incentive to localize every RPG; the localization and publishing process put a potential international release close to the launch of the Nintendo 64 when consumers were reluctant to buy new videogames for a retiring console; Square was already risking that release window with a localization of Super Mario RPG: Legend of the Seven Stars; and the fraught relationship between Nintendo and Square, sparked by mismanagement of the SNES CD-ROM and Square’s subsequent decision to develop their future videogames on Sony’s PlayStation, likely did not help matters.

For almost twenty-five years the only way to play Seiken Densetsu 3 in English was through an unofficial translation on an emulator, a monumental fan effort offset only by the illegality of playing with a downloaded ROM. It seemed destined to remain a Super Famicom exclusive, tantalizing and elusive, until it was unexpectedly included in the Collection of Mana compilation released on Nintendo Switch in 2019, officially localized in English, French, German, and Spanish for the first time. Now with the English title “Trials of Mana,” one of Square’s most lamented unexported RPGs is available internationally for the first time.

Trials of Mana is set in a fantasy world hundreds of years after a magical conflict that endangered all of existence. Salvation came from the Mana Goddess, a manifestation of the Tree of Mana that supports all life and magic. The Goddess used the mystical Sword of Mana to seal away Benevodons, beasts representing the out-of-control elements of Mana, in colossal monoliths. Weakened by the struggle, the Goddess receded into the Mana Tree to rest, leaving humanity’s survivors to rebuild the world.

As I begin Trials of Mana, humanity has rebuilt their civilizations into several small city-states and global destruction once again seems imminent. The Magician Kingdom of Altena is corrupted by the Crimson Wizard, who goads the True Queen into invading the kingdom of Valsena. Nevarl is a kingdom of honorable thieves whose king has fallen under the influence of the lascivious Belladonna, who turns the thieves into pillaging bandits that invade the mountain kingdom Laurent. And Ferolia, the kingdom of Beastmen, has its king swayed by the demon Goremand, who sends the Beastman army to occupy the port city of Jadd and put Holy City Wendel under siege. These three forces do not represent a single enemy’s master plan, but rather the conflicting schemes of three opposing dark powers. Whose plot succeeds and which final boss I will face at Trials of Mana’s finale depends on which character I choose at the outset.

The first decision I make in Trials of Mana is which characters will make up my three-person party. I can choose from among six possible party members, each hailing from either a corrupted or an invaded kingdom. Each character has a unique fighting style and array of spells available to them, but the selection screen does not trouble itself with relaying this information, instead listing the character’s name and job. Some character attributes are easy to deduce with genre experience: Charlotte is a Cleric, commonly responsible for healing magic in RPGs; Angela is a magician, so I can discern that she will be responsible for the party’s offensive magic.

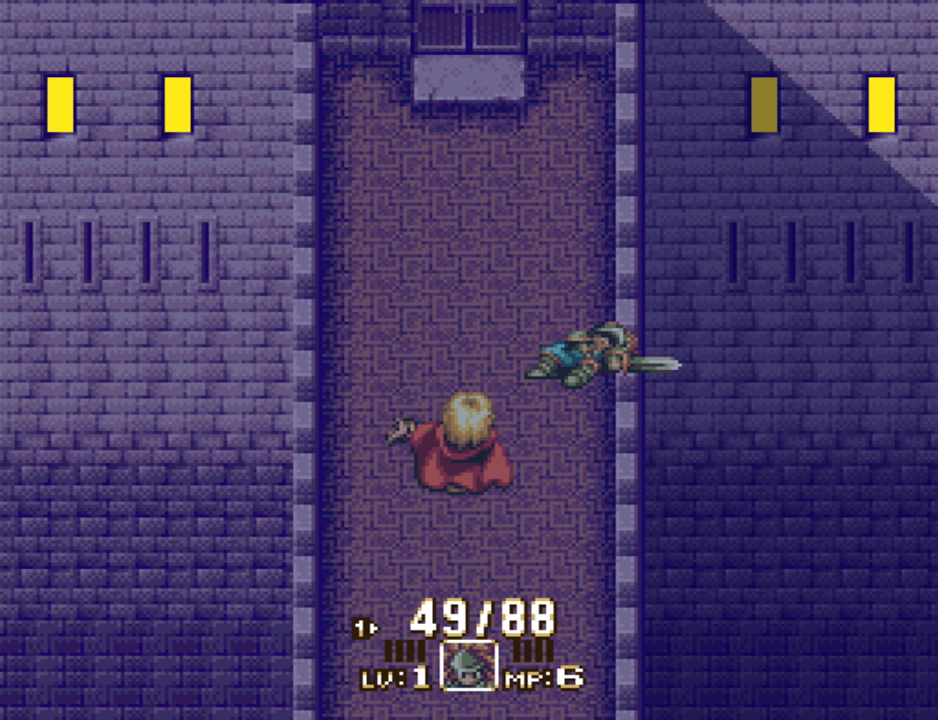

But most vital information is impossible to deduce from a name and a job title. Hawkeye, a Nevarlan thief, dual-wields daggers and hits twice on each attack. Kevin the Ferolian Grappler transforms into a powerful werewolf at night. The only way to learn these essential facts is to play as Hawkeye and Kevin. That there are things I may only discover about a playable character by putting an hour of time into them is bad enough, but characters also change classes as they gain experience levels, learning new skills that change their role in the party.

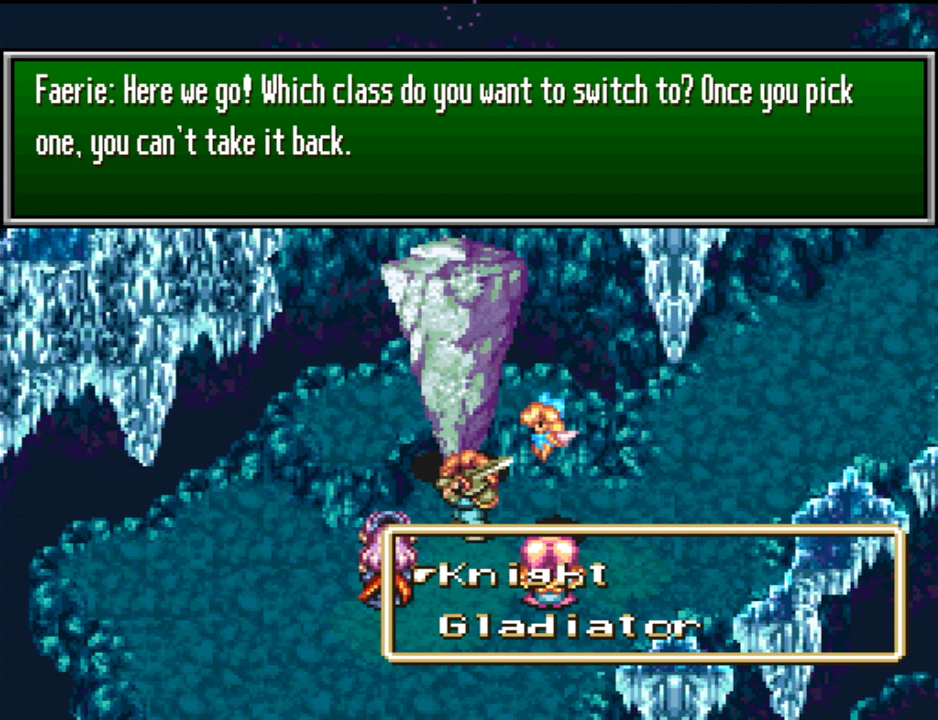

Class changes are branching trees unique to each character. Duran may become a Knight or a Gladiator; one teaches him healing magic, the other teaches him to enchant his sword with the elements of Mana. Nothing communicates this when I am asked to make the decision. Some characters learn powerful combos, called “Techs,” that hit every enemy on screen; others learn Techs that target only one enemy. There’s no way to know except playing for the ten and twenty hours it takes to reach those class changes then playing as them for several hours more to see what abilities they unlock. It’s possible for me, ignorant of how characters change over time, to choose and develop a party that has no healing magic whatsoever. A choice made in ignorance can potentially make the final dungeons much harder, if not impossible.

The solution is to consult an online guide before playing Trials of Mana, but this isn’t possible for every player, and shouldn’t be a requirement in any videogame. I should be given the information I need to make informed decisions, sparing me from discovering a choice I made ten hours ago has rendered the next obstacle impassable. Trials of Mana’s inscrutability is a relic of its time, but even compared to its contemporaries it is egregious.

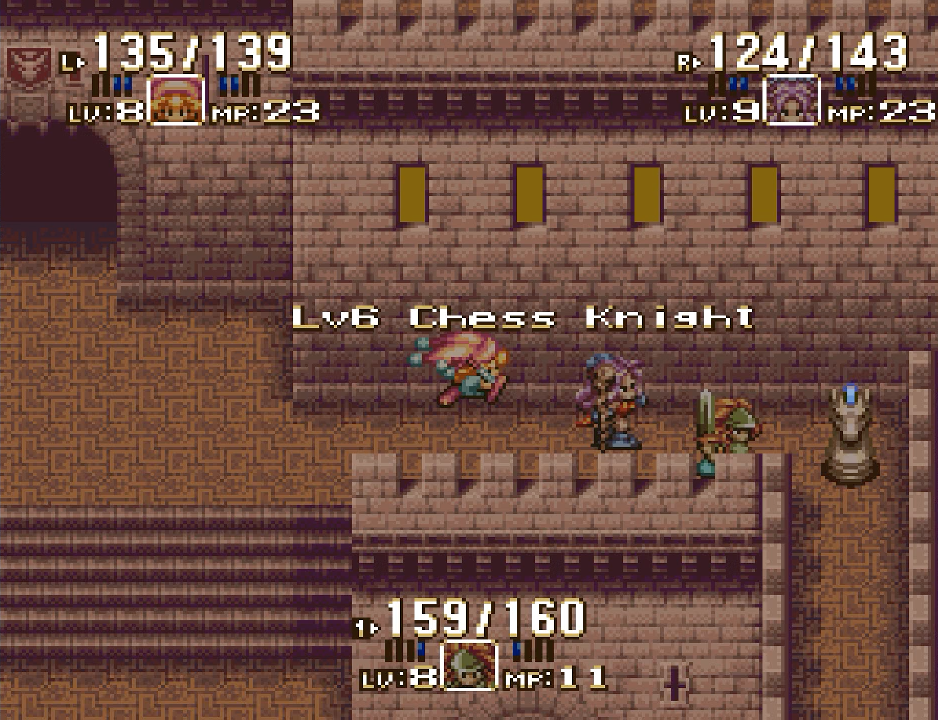

Like the rest of the Mana series, Trials of Mana is an Action RPG. I take direct control of one character in a persistent three-person party while an AI controls the other two. When my party nears an enemy, they draw their weapons. By holding down the A button, my player character enters a combat stance and automatically attacks enemies. As they attack, they build up a power meter which I may expend on powerful Tech abilities unique to each class. Items and magic are cast from the Mana series’ iconic Ring Menu, which pauses the action allowing me time to select and target an item or spell as needed by selecting options from a circular menu that grows around the selected character.

Other Mana videogames can be tediously hack-and-slash-y so it’s refreshing to see that Trials’ combat systems feel familiar while still made distinct by automating attacks with a held button. But this system is not without flaws that compound the deeper in I get.

The automated attacking system is fickle. While I can direct my player character to enter an attacking state, I have little control over what they attack. The best I can do is move my character close to what I want to die and hope the system agrees with me. In dense enemy groups this is nearly impossible which is problematic when there’s a dangerous monster I want to eliminate first. The automated attacking system can also be unresponsive, my character’s attacks ceasing when enemies stand near walls or on staircases, or for no apparent reason at all.

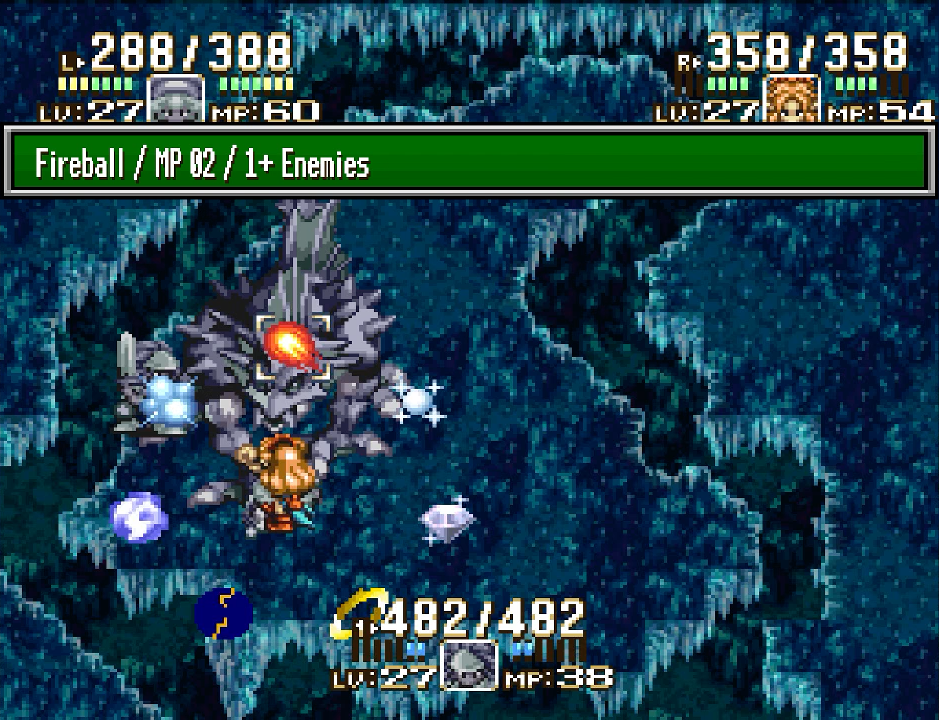

A bigger problem is magic. The Super Famicom hardware isn’t able to simultaneously handle spectacular 16-bit spell effects and player input, so whenever a spell is cast all my input is disabled. The more spellcasters are in battle the more difficult it is to cast spells or use items of my own. Late game enemies are eager to spam magic on my party, so I often find myself hammering the menu button in a desperate bid to heal in whatever brief, invisible window is next available. By the final boss I feel like I am spending more time watching enemy spell animations than actually fighting. Trials of Mana is too often bogged down by so many overlapping systems that it becomes non-responsive, making me feel helpless as I bludgeon buttons hoping a command will register before my party is wiped out.

It doesn’t help that some enemies are designed to punish me when I do take action. After developing my party to high levels and upgrading their classes twice, they have a suite of magic spells and Techs at their disposal which they need against late game enemies. If I use these abilities against enemies, some respond with nukes that will one-shot my entire party, forcing me to fall back on rudimentary attacks. But sometimes enemies use these nukes for no reason! It’s frustrating to walk into a room, my last save a half-hour ago, and my entire party immediately dies in one hit from a powerful enemy attack I can do nothing to predict or curtail. “Unfair” is a word to describe my feelings about these situations. 16-bit era RPGs have a reputation for huge upticks in ferocity in their final dungeons, and Trials of Mana revels in this ethos.

As frustrating and punishing as Trials of Mana’s combat can be, I still enjoyed myself because its scenario design is the most impressive of its era. Each player character has a brief origin story detailing their relationship with their home city and the events that brings them to the port city of Jadd. Stopping the plot for a moment to explore Jadd, I can find the other potential player characters wrapping up their own origin stories. They reappear throughout the story, giving glimpses at their own personal quests, but the character I choose as my main character determines the thrust of the plot and which of the competing villains’ schemes succeeds while supporting characters’ plots fade into the background as their nemeses are eliminated. Some characters’ plots overlap somewhat, but if I want to see every angle of every story I must beat this twenty hour RPG at least six times.

After finishing a unique origin story, Trials of Mana’s plot plays out the same for every character until the third act. Events here call on me to return to every area I’ve visited to challenge new threats, and I can choose to take them on in any order I wish. If I want, I can first return to where I met Lumina, the first Mana Spirit, and deal with the new threat there. Or since I am enamored with Salamando’s character design, I may wish to return to the Fiery Gorge first so I can revisit his home sooner. In every event, there’s something new to explore and enemies scale themselves to keep my party challenged. It’s an effective system that gives me the agency to solve the plot’s current dilemma in the order I choose without removing me entirely from the plot.

On a smaller scale, Trials of Mana has a day/night system. Different enemies appear at different times of day, while Kevin’s more powerful beastman form and Beiser’s seedy Black Market are only available at night. The day of the week also changes as I explore or stay the night at an inn, further impacting the world. I can stay for free at inns on Mana Day, while the enemies of the Burning Sands increase in power on Salamando Day. Time of day is only incidentally useful and I’ve beaten Trials twice now not once paying attention to the day of the week, but it’s impressive seeing these systems dating this far back in console history. Such systems are common today, but it’s interesting witnessing an early example of them here.

It’s not difficult to imagine how Trials of Mana’s reputation was built up in the popular consciousness: Available in English for almost twenty-five years only as a translated ROM, it was played only by passionate fans motivated to seek it out in spite of its illegality. Those players most likely to enjoy it, in other words. It’s not a bad RPG. It possesses many interesting and unique features for its era, but it has many more which feel offputting and opaque. Too many of its systems go unexplained, especially in how the characters I choose and the ways I develop them impact the tools available to me in the endgame. Worse, its tedious combat devolves into an often unfair level of difficulty. There’s a remake due out in a couple weeks as I write this, and Trials of Mana will benefit from one. Given a wide release in 1995 it might have been remembered as a classic, but it survives today as, at best, a curiosity.